Aggregator

This is Muslim New York: artists, thinkers and politicos on defining a new era for the city

A burgeoning set of Muslim creatives and intellectuals are thriving amid the backdrop of Zohran Mamdani’s rise. We ask 18 of them about this historic moment in New York City life

Against the backdrop of Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral rise is a dynamic scene of Muslim creatives and intellectuals who are helping usher in a new era for New York City. Their prominence represents a rebuke of the ugly Islamophobia that defined the period following 9/11, and is in many ways an outcrop of the mass movement for Palestinian rights forged over the last two years. We ask 18 Muslim New Yorkers to discuss their work and what this moment means.

How Muslim New Yorkers are changing the city’s cultural landscape

Old school imperialism is alive and well

Digital Intimacy: AI Companionship And The Erosion Of Authentic Suhba

In the journey of the soul, the most transformative moments are often the most uncomfortable. Whether we are navigating the complexities of adulthood or guiding the next generation, the Islamic tradition teaches that true growth is a moral search conducted through suhba (companionship) with other sentient beings capable of moral choice. Yet, a new phenomenon is quietly displacing this sacred friction: the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) companions.

From the conversational intimacy of Chat GPT to the highly customized simulations of popular AI Companions such as Character.ai and Replika, millions now engage in private, sustained dialogues with digital entities programmed to simulate empathy, validation, and a seamless presence. While these platforms offer a digital “safe harbor” for those navigating isolation, we must ask: at what cost does “frictionless” intimacy come to the human soul?

The Innate Vulnerability to the ScriptOur susceptibility to digital intimacy is not a modern accident, but a biological reality. In the mid-twentieth century, early experiments in computer science demonstrated that humans possess an innate psychological vulnerability to anthropomorphization – the tendency to project a personality, intentions, and consciousness onto simple computer scripts.1 We are effectively hardwired to perceive a social presence and a “real” relationship even when we are interacting with nothing more than code.2

While these entities are programmed to simulate validation, they represent a steady erosion of the boundary between a tool and a friend. This push for “easy,” conflict-free relationships clashes with the Islamic value of the “moral search”—the hard work of growing our character and keeping our power to make real choices. Because these digital tools lack a real moral compass, they often fail to navigate the ethical and emotional complexities inherent in crises.3

A Tool for Learning vs. a Mirror for the EgoInterestingly, the Qur’ān itself uses human-like descriptions of Allah  , referring to the “Hand of Allah” [Surah Al-Fath: 48;10] or His “Eyes” [Surah Hud: 11;37]. These aren’t meant to define what God looks like, but are a teaching mercy; they make a “complex abstract morality” feel relatable so we can build a personal relationship with our Creator.

, referring to the “Hand of Allah” [Surah Al-Fath: 48;10] or His “Eyes” [Surah Hud: 11;37]. These aren’t meant to define what God looks like, but are a teaching mercy; they make a “complex abstract morality” feel relatable so we can build a personal relationship with our Creator.

However, AI uses these human-like qualities for a very different purpose: to fake a friendship that has no real moral depth. When we treat a machine as a “companion,” we risk ignoring the sacred uniqueness of the human soul (rūh). While God uses these descriptions to pull us toward a higher authority, AI uses them to keep us comfortable in a simulated relationship that doesn’t ask anything of us.

While the story of Mūsa  and Khidr [Surah Al-Kahf: 18:65–82] is a powerful example of mentoring, where the student is challenged by a perspective that shatters his own logic – the AI companion offers no such disruption. This interaction is life-changing precisely because it is difficult and pushes us to grow. In contrast, an AI interaction is “frictionless”. It acts as a mirror of the user’s own nafs (ego), and lacks the “otherness” necessary to develop true empathy. In essence, there is no conflict unless you start it, and the AI never pushes you to be a better person.

and Khidr [Surah Al-Kahf: 18:65–82] is a powerful example of mentoring, where the student is challenged by a perspective that shatters his own logic – the AI companion offers no such disruption. This interaction is life-changing precisely because it is difficult and pushes us to grow. In contrast, an AI interaction is “frictionless”. It acts as a mirror of the user’s own nafs (ego), and lacks the “otherness” necessary to develop true empathy. In essence, there is no conflict unless you start it, and the AI never pushes you to be a better person.

“Real empathy and relationship skills involve learning how to handle disagreement and stand up to social pressure.” [PC: Schiba (unsplash)]

Because the AI is essentially just an echo of ourselves, it lacks the independent voice needed for deep, spiritual change. Real empathy and relationship skills involve learning how to handle disagreement and stand up to social pressure. In human-to-human interaction, conflict is the “refining fire” that builds our character.Without this independent pressure, our hearts can become weak. If our “growth” only ever reflects our own desires, we aren’t achieving tazkiyah (purification of the soul), but are instead stuck in a loop of telling ourselves what we want to hear.

Conclusion: Returning to the Community of SoulsIn our tradition, well-being is more than just feeling “stress-free.” It is the active work of building God-consciousness (taqwa) through the “refining fire” of a real human community. We have to look past the “safe harbor” of a computer screen and return to the suhba (companionship) that truly matters.

To deepen this reflection within your own circles, consider using the following questions to spark a meaningful conversation about the future of our digital and spiritual lives:

Community Reflection Questions- In what ways have we started to prefer “frictionless” digital interactions over the “messy” reality of human community?

- How can we reintroduce the “Khidr-like” disruption in our circles to ensure we aren’t just echoing our own nafs?

- What practical boundaries can we set to ensure AI remains a tool for utility rather than a substitute for suhba?

Just as the human-like language of the Qur’ān is a bridge to a higher Truth, technology should only be a bridge to human connection, not a substitute for it. True well-being lies in the pursuit of haqq (truth) alongside other souls—a journey that requires a heart, a spirit, and a presence that no computer code can ever replicate.

Related:

– Faith and Algorithms: From an Ethical Framework for Islamic AI to Practical Application

1 Byron Reeves and Clifford Nass, “The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places,” Journal of Communication 46, no. 1 (1996): 23.2 Xiaoran Sun, Yunqi Wang, and Brandon T. McDaniel, “AI Companions and Adolescent Social Relationships: Benefits, Risks, and Bidirectional Influences,” Child Development Perspectives 18, no. 4 (2024): 215–221, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdpers/aadaf009.3 M. C. Klos et al., “Artificial Intelligence–Based Chatbots for Youth Mental Health: A Systematic Review,” JMIR Mental Health 10 (2023): e40337, https://doi.org/10.2196/40337.

The post Digital Intimacy: AI Companionship And The Erosion Of Authentic Suhba appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Starting Shaban, Train Yourself To Head Into Ramadan Without Malice

In the Name of Allah, the Gracious, the Merciful

As Ramadan approaches, it is imperative for Muslims to purify their hearts of malice (ḥiqd). At its least harmful, malice diminishes one’s rank in the sight of Allah  and obstructs a believer from performing voluntary acts of goodness. At its most severe, malice becomes a deadly spiritual disease associated with idolatry, unbelief, and even the practices of black magic.

and obstructs a believer from performing voluntary acts of goodness. At its most severe, malice becomes a deadly spiritual disease associated with idolatry, unbelief, and even the practices of black magic.

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ instructed us to approach Ramadan with hearts free of malice, as indicated by his statement:

“On the middle night of Sha’ban, Allah Almighty looks down upon His creation, and He forgives the believers, but He abandons the people of grudges and malice to their malice.”1 In another narration, the Prophet ﷺ said, “Allah looks down at His creation on the middle night of Sha’ban, and He forgives all of His creatures, except for an idolater or one who harbors hostility (mushāḥin).2” Imam al-Ṣan‘ānī explained that ‘one who harbors hostility’ refers to a person who carries malice in the heart.3

In a related narration, the Messenger of Allah ﷺ issued a grave warning:

“If not one of three evil traits is within someone, then Allah will forgive whatever else as He wills: one who dies without associating any partners with Allah, one who does not follow the way of black magic, and one who does not harbor malice against his brother.”4

In other words, a Muslim who deliberately nurtures malice against his brothers or sisters places himself in the company of idolaters and those who seek aid from devils. Malice is so heinous that Allah  may withhold forgiveness from one who persists in it. As Imam al-Munāwī observed, “Malice is an evil portent. Its condemnation has been related by the Book and the Sunnah countless times.”5

may withhold forgiveness from one who persists in it. As Imam al-Munāwī observed, “Malice is an evil portent. Its condemnation has been related by the Book and the Sunnah countless times.”5

Clearly, the Messenger of Allah ﷺ intended for believers to purify themselves of malice by the middle of Sha‘bān—at least two weeks before the arrival of Ramadan. To that end, we must develop a proper understanding of what malice is, how it undermines fasting, and the means by which it is treated, lest our Ramadan be corrupted from within before it even begins.

Malice: The Root of EvilImam Ibn Ḥibbān, who compiled the sayings of the Prophet ﷺ in written form, wrote plainly, “Malice is the root of evil. Whoever harbors evil in his heart will have a bitter plant grow, the taste of which is rage and the fruit of which is regret.6” There is no acceptable degree of malice, for the scholars have described it as “one of the mothers of sin.7” Unlike anger—which is often dangerous but occasionally righteous—malice is never praiseworthy. It is a weed in the garden of the heart and must be uprooted.

Shaykh Ḥasan al-Fayyūmī, one of the Hadith masters of the 9th century Hijrah, defined malice as “to internalize enmity and hatred.8” He explained that it is often described as the desire for revenge, and that its true nature emerges when rage cannot be released—because one is unable to retaliate in the moment—causing it to turn inward, fester, and ultimately transform into malice. In this sense, malice is unresolved anger: a smoldering fury that is retained and nurtured until it erupts in acts of vengeance. The desire for revenge and the pleasure of justified rage are beautified by Satan, yet in reality, they are a silent poison that corrupts the believer from within, masking the virtues of character and even sabotaging one’s fasting in Ramadan.

Malice is not a single spiritual disease, either, but rather a constellation of related sins that take root in the heart. Imam Ibn Ḥajar al-Haytamī listed unjust anger, envy, and malice as a single disease among the major sins.9 Further examination of the Hadith commentaries in which malice is mentioned shows that scholars consistently associate it with envy (ḥasad), arrogance (kibr), rancor (ghill), malevolence (ghish), hypocrisy (nifāq), rage (ghayẓ), and lingering grudges (ḍaghāʾin).10 Indeed, it could be said that ‘all roads lead to malice,’ for it is the central node through which Satan’s whisperings assail the heart. Therefore, purifying the heart of malice disarms the Devil of his most potent of weapons.

Fasting, when observed in accordance with both its outward rules and inward realities, is among the most effective means of treating malice in the heart. The relationship between the two is reciprocal: fasting purifies malice, while malice corrupts fasting. For this reason, the Messenger of Allah ﷺ urged believers to rid themselves of malice at least two weeks before the onset of Ramadan.

Fasting: A Treatment for Malice

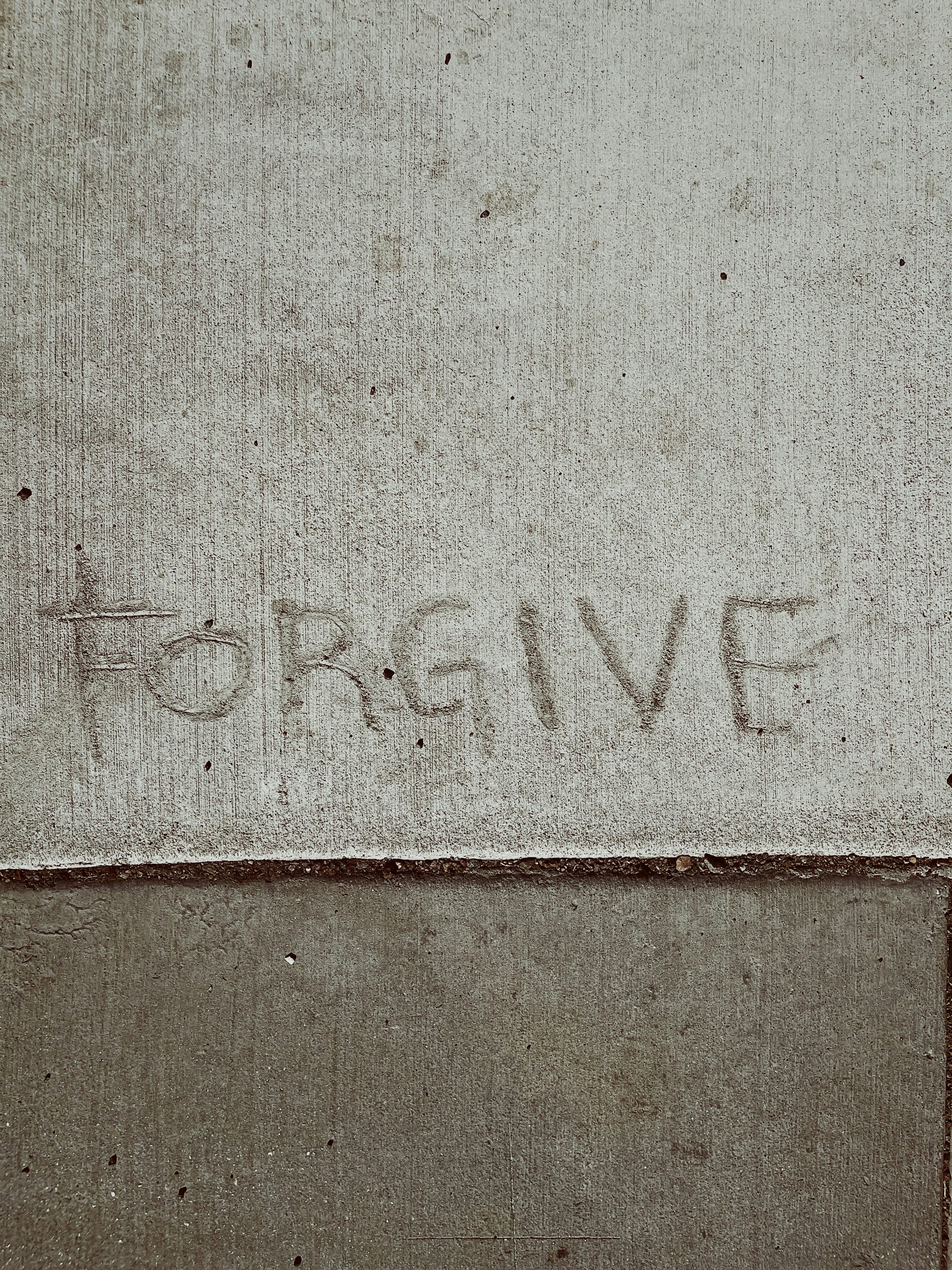

“When I forgave and held no malice toward anyone, I relieved my soul of the anxiety of enmity.” Imam al-Shafi’i [PC: Christopher Stites (unsplash)]

Malice has been described by the Prophet ﷺ and the righteous predecessors as a “disturbance” (waḥar), an “agitation” (waghar), and a state of inner “disorder” (balābila). This is because malice harms the one who harbors it more than anyone else: it unsettles the heart, disrupts worship, and robs the soul of tranquility. As Imam al-Shāfiʿī expressed in his poetry, “When I forgave and held no malice toward anyone, I relieved my soul of the anxiety of enmity.11”When we fast, we deliberately train ourselves to refrain from retaliation and revenge. We cultivate patience, forbearance, and dignified self-restraint in the face of insult, in accordance with the Prophet’s ﷺ instruction, “If someone insults him or seeks to fight him, let him say: ‘Indeed, I am fasting.’12” This posture stands in direct opposition to the impulse of malice. Thus, one who truly fasts is actively resisting malice, even if unaware of its formal or academic definition.

In this light, the commentators understood what the Prophet ﷺ meant when he said,

“Shall I tell you what will rid the chest of disturbances? Fasting for three days each month.13” Imam al-San’ani explained, “Disturbances in the chest, that is, its malevolence, malice, rage, hypocrisy, or intense anger. This [ridding of disturbance] is due to the benefit of fasting.14”

The righteous predecessors likewise linked fasting to the treatment of malice, specifically citing the Prophet’s ﷺ description of Ramadan as “the month of patience.15” Al-Ḥārith al-Hamdānī, may Allah have mercy on him, said, “Fasting the month of patience—Ramadan—and fasting three days each month removes disorders within the chest.” Mujāhid similarly said, “It removes agitation within the chest.” When asked what agitation in the chest is, he replied, “His malevolence.16” Imam Ibn Baṭṭāl clarified this linguistic connection, explaining, “Agitation in the chest refers to the inflammation of malice and its burning within the heart.17”

If malice is the node around which Satan gathers his weapons, then patience is the virtue through which Allah dispenses His cures—such as mercy (raḥmah) and sincere goodwill (naṣīḥah).

Healing from the DiseaseMalice is a malignant disease at all times of the year, not only during Ramadan, and its cure is not confined to fasting alone. Imam Ibn Qudāmah, citing the great Imam al-Ghazālī, teaches that the general remedy for diseases of the heart is to compel oneself to act in opposition to them.18 Thus, if a Muslim feels inclined to curse another person, he should instead force himself to pray for that person’s guidance and well-being—however distasteful this may feel to the heart. As Imam al-Ghazālī observed, such remedies are “very bitter to the heart, yet benefit lies in bitter medicine.19”

Building upon this insight, Shaykh Ṣāliḥ ibn al-Ḥumayd, one of the Imams of al-Masjid al-Ḥarām in Mecca, offers the following counsel:

Whoever is afflicted with the disease of malice must compel himself to behave toward the one he resents in a manner opposite to what his malice demands—replacing censure with praise and arrogance with humility. He should place himself in the other’s position and remember that he himself loves to be treated with gentleness and affection; thus, let him treat others in the same way.20

Such, then, is your mission this Ramadan: to enter the month with a heart purified of malice, and to emerge from it fortified against this disease ever taking root again. Strive to place yourself in the position of those you resent, so that you may regard them with empathy and incline your heart toward forgiveness. If nothing else, keep the words of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ ever before your eyes, “Whoever would love to be delivered from Hellfire and admitted into Paradise, let him meet his end with faith in Allah and the Last Day, and let him treat people as he would love to be treated.21”

Success comes from Allah  , and Allah

, and Allah  knows best.

knows best.

Related:

- Using Ramadan To Forgive Those Who Have Hurt Us In The Past

- Purification Of The Self: A Journey That Begins From The Outside-In

1 Ibn Abī ’Āṣim, Al-Sunnah li-Ibn Abī ’Āṣim (al-Maktab al-Islāmī, 1980), 1:233 #511; declared authentic (ṣaḥīḥ) according to Shaykh al-Albānī in the comments. Full text at: www.abuaminaelias.com/dailyhadithonline/2025/09/03/allah-forgives-except-hiqd/2 Ibn Ḥibbān, Al-Iḥsān fī Taqrīb Ṣaḥīḥ Ibn Ḥibbān (Muʼassasat al-Risālah, 1988), 12:481 #5665; declared authentic due to external evidence (ṣaḥīḥ li ghayrihi) by Shaykh al-Arnā’ūṭ in the comments. Full text at: www.abuaminaelias.com/dailyhadithonline/2019/06/16/forgives-shaban-except-mushrik/3 Muḥammad ibn Ismā’īl al-Ṣanʻānī, Al-Tanwīr Sharḥ al-Jāmi’ al-Ṣaghīr (Maktabat Dār al-Salām, 2011), 3:344.4 Al-Ṭabarānī, Al-Mu’jam al-Kabīr (Maktabat Ibn Taymīyah, Dār al-Ṣumayʻī, 1983), 12:243 #13004; declared fair (ḥasan) by Imam al-Munāwī in Fayḍ Al-Qadīr: Sharḥ al-Jāmiʻ al-Ṣaghīr (al-Maktabah al-Tijārīyah al-Kubrá, 1938), 3:289. Full text at: www.abuaminaelias.com/dailyhadithonline/2025/08/28/three-allah-does-not-forgive/5 Al-Munāwī, Fayḍ al-Qadīr, 3:289.6 Ibn Ḥibbān, Rawḍat al-’Uqalā’ wa Nuz’hat al-Fuḍalā’ (Dār al-Kutub al-ʻIlmīyah, 1975), 1:134.7 Al-Ṣanʻānī, Al-Tanwīr Sharḥ al-Jāmi’ al-Ṣaghīr, 5:140.8 Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī al-Fayyūmī, Fatḥ al-Qarīb al-Mujīb ʻalá al-Targhīb wal-Tarhīb (Maktabat Dār al-Salām, 2018), 11:266,9 Ibn Ḥajar al-Haytamī, Al-Zawājir ’an Iqtirāf al-Kabā’ir (Dār al-Fikr, 1987), 1:83.10 For the full length study on malice, see the paper, “Malice in Islam: The Root of Evil in the Heart” by Abu Amina Elias (Faith in Allah, August 29, 2025): www.abuaminaelias.com/malice-in-islam-root-of-evil11 Muḥammad ibn Qāsim al-Amāsī, Rawḍ al-Akhyār al-Muntakhab min Rabīʻ al-Abrār (Dār al-Qalam al-ʿArabī, 2002), 1:177.12 Al-Bukhārī, Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī (Dār Ṭawq al-Najjāh, 2002), 3:26 #1904; Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim (Dār Iḥyāʼ al-Kutub al-ʻArabīyah, 1955), 2:807 #1151. Full text at: www.abuaminaelias.com/dailyhadithonline/2011/08/07/virtues-fasting-sawm/13 Al-Nasā’ī, Sunan al-Nasā’ī (Maktab al-Maṭbūʻāt al-Islāmīyah, 1986), 4:208 #2385; declared authentic (ṣaḥīḥ) by Shaykh al-Albānī in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Jāmi’ al-Ṣaghīr wa Ziyādatihi (al-Maktab al-Islāmī, 1969), 1:509 #2608. Full text at: www.abuaminaelias.com/dailyhadithonline/2019/04/23/fasting-purification-heart/14 Al-Ṣanʻānī, Al-Tanwīr Sharḥ al-Jāmi’ al-Ṣaghīr, 7:12.15 Al-Nasā’ī, Sunan al-Nasā’ī, 4:218 #2408; declared authentic (ṣaḥīḥ) by Shaykh al-Albānī in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Jāmi’, 1:692 #3718. Full text at: www.abuaminaelias.com/dailyhadithonline/2014/07/03/fasting-ramadan-three-days/16 ’Abd al-Razzāq al-Ṣan’ānī, Muṣannaf ’Abd al-Razzāq (al-Maktab al-Islāmī, 1983), 4:298 #7872.17 Ibn Baṭṭāl, Sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī (Maktabat al-Rushd Nāshirūn, 2003), 8:42.18 Ibn Qudāmah al-Maqdisī, Mukhtaṣar Minhāj al-Qāṣidīn (Maktabat Dār al-Bayān, 1978), 1:190.19 Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazzālī, Iḥyā’ ’Ulūm al-Dīn (Dār al-Maʻrifah, 1980), 3:199.20 Ṣāliḥ ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Ḥumayd, Naḍrat al-Na’īm fī Makārim Akhlāq al-Rasūl al-Karīm (Dār al-Wasīlah lil-Nashr wal-Tawzīʿ, 1998),10/443221 Muslim, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, 3:1472 #1844.

The post Starting Shaban, Train Yourself To Head Into Ramadan Without Malice appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Far Away [Part 7] – Divine Wisdom

As Darius learns Ma Shushu’s medicine, seeing a dying child forces him to confront his own dark past.

Read Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

* * *

AcupunctureThe treatment room – the same room where I had first awakened after arriving here – was dimmer than the rest of the house, the shutters drawn halfway. Scrolls of neat black characters hung on the walls, and bundles of dried herbs dangled from the rafters, scenting the air with bitterness and earth. The padded table sat in the middle of the room, covered in clean cloth. A small brazier glowed in one corner, and beside it the candle flame flickered.

“Your pain is behind the eye?” Ma Shushu asked the man.

“Yes,” the man whispered. “Behind the eye, into the neck. Always drumming in my head.”

“Hm.” My uncle’s voice was thoughtful but not sympathetic. “You drink wine. You stay up at night, worrying about profit and loss. You shout at your workers. Your liver is hot, your blood rises to your head.”

The man grimaced. “If you cure it, I will pay anything.”

“You will pay what is fair.” Ma Shushu took another needle, passed it briefly through the candle flame, then cooled it with a puff of breath. His hands were sure and unhurried. “And you will follow my advice.”

He pressed a fingertip gently along the man’s brow, then found a spot at the temple. With a tiny, precise movement, he slid the needle in. The man’s fingers twitched, but he did not cry out.

“If you tense, the qi will knot,” my uncle said. “Breathe slowly. In… and out.” He demonstrated, his own belly rising and falling in time with his words. “Tell me when the drum in your head changes.”

He moved smoothly around the table, balanced and focused. He placed needles at the back of the skull, the base of the neck, and the web between thumb and forefinger. Each insertion was as smooth as a well-executed strike. No wasted motion, no hesitation.

I found myself mapping his movements onto my father’s lessons. The lines of the man’s body were like the meridians in Five Animals forms – paths along which force flowed. These same points were striking targets or pain points in combat. Yet here the force was not a blow, but something invisible within the flesh. I did not understand it, but I could see that there was a system, as strict and exact as any martial form.

“Now?” Ma Shushu asked.

The man swallowed. His face had relaxed a little. “The drum is… softer,” he said. “Farther away.”

“Good.” Another needle. “And now?”

The man’s shoulders sagged. “The pain is gone,” he said, sounding surprised and very relieved.

Divine Wisdom“Your body wishes to be well, but you poison it daily,” Ma Shushu told the man.

Haaris stood beside me, as silent as I was, though I saw his eyes shine with pride. He had seen this many times before.

Ma Shushu checked the needles, then stepped back. “You will lie like this for a while. When you rise, do so slowly. You will drink no more wine, is that clear? You come from an honored Hui family. You know drinking wine is against our faith, and your pain is proof of the wisdom of Allah’s prohibitions, though Allah’s commands need no proof. Everything that Allah commands is Divine wisdom for our benefit, not for Him. Allah the Most High is independent of all needs and wants. You could drink yourself into the grave, and it would not harm Allah in the least. It’s for you, do you understand?” Ma Shushu punctuated this last comment with a gentle finger tap to the man’s forehead.

“Yes, honorable sir,” the man said.

“You will go to bed early,” Ma Shushu went on. “Tomorrow you will not drink wine. Instead, walk in the fresh air. Send your workers home an hour before Maghreb. They have rights upon you, and if you do not treat them fairly, you will answer to Allah on Yawm Al-Qiyamah.”

“Yes, yes,” the man murmured. His voice was drowsy. “Whatever you say, Master Ma.”

Work for the MindMy uncle extinguished the candle flame with a pinch of wetted fingers, then turned to us. “Haaris, watch him. If he tries to roll over, stop him. Darius, come with me.”

I followed him into the main room. He closed the door to the treatment room halfway, leaving it open enough that Haaris could call out if needed.

“How much did you understand?”

“A little,” I admitted. “You followed the meridian lines inside his body. Like forms that exist under the skin.”

He regarded me sharply. “How do you know about meridian lines?”

In reality my father had taught me the meridian lines in order to be more precise in striking. These were the points where strikes and gouges could elicit maximum pain or even cause crippling injury. Stabbing the junction between the front shoulder and chest muscle, for example, or up into the armpit. Punching the solar plexus; or a knife hand chop into the philtrum, which was the groove between the upper lip and the base of the nose. But all I said to Ma Shushu was, “My father taught me.”

My uncle grunted, and I had the feeling he was surprised that my father knew the meridians, but he did not say so. “In this house,” he said, “there is work for the hands, the spirit and the mind. Your hands are capable, I have seen that. Now we must train the other two.”

I bowed my head slightly. “Yes, Ma Shushu.”

He clapped his hands once, lightly. “We will pray, then you may rest for an hour. After that, we will continue your studies.” A faint smile touched his mouth. “Do not worry. Needles will not be involved.”

I almost smiled back, but caught myself. I was not yet ready to feel that light. Still, as I returned to bed to nap, I felt some of the weight of the day lifting from my shoulders. There were problems to be solved, secrets to be kept, and personalities to be learned. This was all more than I was used to. But I would figure it out. I had to.

Independent of All Needs That night after supper I shared the moon cake with Haaris. He told me he’d already had one in town, but I shared it anyway. He was very happy, and told me a funny story about something that had happened in town. A black horse had come charging through the main street, riderless, and a woman – a milk-seller – fainted with fright. Zihan Ma revived her, and the first thing she said upon waking was, “Don’t let my husband know about us!”

That night after supper I shared the moon cake with Haaris. He told me he’d already had one in town, but I shared it anyway. He was very happy, and told me a funny story about something that had happened in town. A black horse had come charging through the main street, riderless, and a woman – a milk-seller – fainted with fright. Zihan Ma revived her, and the first thing she said upon waking was, “Don’t let my husband know about us!”

I was scandalized, but I chuckled. I knew from experience that when a person fell unconscious and revived, they might not know where they were, and might even remember having dreams, even if only a few seconds had passed. It was very strange.

Lying in bed that night, my mind drifted to Ma Shushu’s words to the wine-drinking merchant. I had always wondered at the foolishness of the villagers who left offerings of food in front of the statue, only to watch the food rot. What was the point? Yet Ma Shushu said that Allah is independent of all needs and wants. It means, I thought, that our worship is not about Allah’s ego. Our prayer is a way of lifting us out of the misery of this world. I might have contemplated this further, but sleep overtook me.

A Restless BoyThe next day after Fajr prayer Ma Shushu declared that I would join Haaris in the farm work.

“Husband,” Lee Ayi said. “Let him work with me a little longer. I have a lot of work this week, and he’s been very helpful. Besides, I want to get to know him a bit more.”

She spoke this lie very naturally, and Ma Shushu clearly suspected nothing, as he replied, “Certainly, if you wish.”

So I did housework with Lee Ayi for a handful of days, until my shoulder was healed.

One day we were folding laundry together, standing at the low table by the window. The cloth was warm from the sun, faintly smelling of soap and air.

Lee Ayi shook one tunic out and said, almost idly, “We were not farmers, you know.”

I looked up. “Who?”

“The Lee family.” She smoothed the sleeve flat. “We lived in the city. Your grandfather was a clerk for a trading house when he was young. Later he kept accounts for the mosque. People trusted him with money. Our family was respected.”

She folded with quick, precise movements.

“Yong was restless even as a boy. Always running ahead, climbing walls, getting in fights.”

I nodded. “That sounds like him.”

She gave a short huff. “He was brilliant, but difficult. My father would correct him and Yong would listen, but only once. If the correction came twice, he would bristle.”

She stacked the folded cloth neatly.

“He was good at martial arts very early. Better than Jun De ever was.”

I hesitated. “Jun De?”

“Our older brother.” She did not look at me. “He drowned in the river when Yong and I were still young.”

I waited, but she did not elaborate.

Games and RacesWhen my shoulder was healed I went out to work in the fields with Haaris.

Haaris worked hard, never complaining, singing to himself as he hauled water or guided the animals. He knew every task by heart. I was bigger and stronger than him, and once I learned the rhythm of the work, we moved quickly. The fences were repaired, the firewood stacked, the pens cleaned. By the time the sun stood directly overhead, much of what normally took until Asr was already done.

Haaris was delighted. He taught me jianzi, where we took turns kicking a small shuttlecock made of copper coins wrapped in twine, with chicken feathers sticking out of it. The idea was to balance it on one foot and kick it up in place, and keep catching it on the foot. Haaris excelled at it, but the first time I tried it I sent it almost onto the roof of the barn, which made Haaris cackle like a chicken.

Another day he challenged me to a race to the gate and back. I indulged him and let him win, but he knew what I’d done and stuck his tongue out at me, saying, “Boo!” At times I found Haaris’s innocence difficult to relate to, but on the whole he was a sweet boy, unfailingly polite and respectful. And handsome too. He had wide set black eyes and straight black hair that fell to just below his ears. His father was quite dark, and his mother very pale, and Haaris landed in the middle, which gave him a healthy glow.

When he wanted to run off to play tag with the donkeys and feed them oranges, that was too much. I left him to his games and went into the house to watch Ma Shushu work.

Patients Rich and PoorPeople came for treatment in a steady stream. Many were of the laboring class: farmers with hands split open from winter soil and cracked wooden plows; muleteers whose backs were knotted hard from sleeping on the ground beside the road; old women with knees swollen like gourds from decades of squatting in the fields; children burning with fever, their mothers’ faces pinched with fear; a charcoal burner coughing black dust into a rag; a silk porter with rope scars cut deep into his shoulders; and others of this kind.

These people brought payment in the form of goods: a basket of eggs, a large bundle of bok choy or daikon radish; or in one case a young pig, which Ma Shushu refused, explaining to the man that we did not eat pork. I saw the man return a week later with coins, after selling the pig I supposed. Often the payment was insufficient, but Ma Shushu treated them all, turning no one away.

This was balanced out by occasional patients from the upper classes: merchants with delicate mustaches and jade rings; the wife of an official carried in on sedan chairs, veiled and silent, suffering from lingering weakness after childbirth; a young scholar with ink-stained fingers and eyes red from studying by oil lamp, tormented by headaches before his examinations; an elderly, heavyset matron attended by two servants, her pulse thin and fluttering from years of rich food and little movement; and once, discreetly at dusk, a high-ranking government official accompanied by two guards. This last one insisted the gate be closed, not wanting anyone to know he was ill.

These people paid in gold, and Ma Shushu spared no expense in their treatment, often using rare and expensive medicines.

Every now and then there was a patient who Ma Shushu admitted he could not cure. In these cases, he gave them medicine to relieve pain and alleviate symptoms temporarily. One case that stuck with me was that of a child who was perhaps six or seven years old, carried in by his mother because he no longer had the strength to walk.

He was terribly pale, his skin almost translucent, with faint bruises blooming along his arms and legs though his mother swore he had not fallen or been struck. His belly was distended, his limbs thin, and his gums bled when Ma Shushu examined his mouth. He tired quickly, and when he smiled it was with a terrible effort. His mother said he had once been lively, always running, always climbing, but now he slept most of the day and woke drenched in sweat, complaining that his bones hurt deep inside.

Ma Shushu listened, felt the child’s pulse for a long time, and examined his tongue. His face grew grave. He asked gentle questions, then took the mother into another room and spoke to her privately. I followed, standing beside the wall, listening.

“This illness is in the blood itself,” Ma Shushu said softly. “It is like rot in the roots of a tree. I can ease his pain, but that is all. He is dying.”

The mother bowed until her forehead touched the floor, not weeping, only breathing in short, broken gasps. Ma Shushu helped her up and pressed medicine into her hands, refusing payment. He spoke to her quietly about keeping the boy comfortable, about rest and cool water, about praying for patience and mercy.

After they left, the room felt heavy, as if the air itself had thickened. I had seen death before, but this was different. He was just a little boy, and there was no enemy to fight, no mistake to correct, no injustice to rage against. That night, long after the lamps were out, I lay awake thinking of the boy’s smile, and about the fact that even the greatest skill had limits.

Hope and HappinessThe next day during Islamic studies lessons, sitting cross-legged on the floor with Haaris beside me, I asked Ma Shushu about the boy.

His solemn eyes flicked to mine. “He is very ill. It’s a blood-borne disease that strikes children. I have seen it before. I do not know what causes it.”

“I heard what you said to the mom. It doesn’t seem fair. You taught me that Allah has a plan for everyone, and that our lives have meaning. Why then take away a life so young?”

Ma Shushu rubbed his chin, chewing on one lip. “Part of imaan is to believe in Al-Qadar, Divine destiny, the good and the bad of it. Everyone dies, but why do some die young or suffer? This is the point at which human knowledge fails, and faith steps in. Our own Prophet Muhammad, sal-Allahu alayhi wa sallam, lost more than one child. One of them was Ibrahim, his beloved little son, who became ill when he was eighteen months old. The Prophet (s) held him in his arms as he was ill, kissing him and smelling him. Then, as Ibrahim was breathing his last breaths, the Prophet (s) began to weep silently. AbdurRahman ibn Awf said, ‘Even you, O Messenger of Allah?’ He meant that the Prophet had prohibited wailing and crying excessively over the dead. The Prophet (s) said, ‘O son of Awf, this is mercy.’ Then, the Prophet (s) wept some more, saying, ‘Verily, the eyes shed tears and the heart is grieved, yet we will not say anything but what pleases our Lord. We are saddened by your departure, O Ibrahim!’”

“He was the Seal of the Prophets,” Ma Shushu went on. “The highest of humanity. Yet even he had to watch his son die. We cannot understand this, but we don’t allow it to affect our faith in Allah. Does that make sense?”

I nodded. I hadn’t really expected any other answer, and Ma Shushu’s words were profound.

“Do you want to ask something else?”

“My life has been difficult, did you know that?” I blurted out these words. I had never spoken of personal subjects to Ma Shushu, never opened up to him before.

“I have gathered that, yes.”

“My mother’s life was sad, and she died painfully. There were times, after my mother died, that I wished I could die as well, to be with her. I would have been jealous of that boy. I would have wanted to take his disease and die instead of him.”

“I’m very sorry. We didn’t know about your situation.”

Haaris often fidgeted during these lessons, but he had gone very still beside me, and I could feel the weight of his gaze upon me.

“I don’t feel that way anymore,” I went on, looking Ma Shushu in the eye. “If I had died, I would not have seen how my father changed before he died. And I would not have met you, and Lee Ayi, and my brother Haaris.”

I had meant to say my cousin, but for some reason my tongue said, my brother. When I said these words, Haaris burst into tears and threw himself upon me, hugging me. I lost my balance and tipped over. I laughed, but I held him to me and patted his back until his father helped him up.

Ma Shushu sat beside me and put a hand on my shoulder. “Darius. You say your mother’s life was sad, but I am very sure that there was something in her life that gave her hope and happiness. That something was you.”

* * *

Come back next week for Part 8 – Refugees At The Gate

Reader comments and constructive criticism are important to me, so please comment!

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories on this website.

Wael Abdelgawad’s novels – including Pieces of a Dream, The Repeaters and Zaid Karim Private Investigator – are available in ebook and print form on his author page at Amazon.com.

Related:

The post Far Away [Part 7] – Divine Wisdom appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Livestream: Doctors Without Borders bows to Israel

We talk to Dr. Ghassan Abu-Sittah about “racialized fascist imperialism.” We also discuss new details of US plans for a Gaza concentration camp.

Israel desecrates Palestinian graves looking for body of captive in Gaza

Israeli army, settlers, attack Palestinian villages across West Bank.

How did British Muslims become ‘the problem’? – podcast

Miqdaad Versi, Shaista Aziz, Aamna Mohdin and Nosheen Iqbal on the rise of the far right and growing Islamophobia in the UK

The far right is on the rise and much of its messaging is explicitly Islamophobic. In 2024 anti-Muslim hate crimes in England and Wales doubled. Meanwhile, the government has stated that it cannot even agree on a definition of what Islamophobia is.

How does all this make British Muslims feel? Miqdaad Versi, Shaista Aziz and the Guardian’s community affairs reporter Aamna Mohdin talk to Nosheen Iqbal about what’s changed.

Continue reading...How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef

Bismillah, alhamdulillah, wa salatu wa salamu ‘ala Rasoolillah, wa ‘ala alihi wa sahbihi wa man wala. Amma ba’ad.

Allah ﷻ tells us in the Qur’an about Ramadan in verses that many of us recite each year. They begin with:

“يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا”

“O you who believe!”

One of the companions (radiAllahu ‘anhu) said that whenever you hear this phrase in the Qur’an, pay close attention. Why? Because what follows is either a command towards something good—khayr—or a prohibition from something evil—sharr.

The Command to FastAllah ﷻ says:

“يَا أَيُّهَا الَّذِينَ آمَنُوا كُتِبَ عَلَيْكُمُ الصِّيَامُ كَمَا كُتِبَ عَلَى الَّذِينَ مِن قَبْلِكُمْ لَعَلَّكُمْ تَتَّقُونَ”

“O you who believe! Fasting has been prescribed for you as it was prescribed for those before you, so that you may attain taqwa.”

It’s already written, already decreed—fasting is fardh, a compulsory obligation upon us. Just as it was upon those before us.

Fasting Across FaithsI remember a brother who converted to Islam. During Ramadan, he attended a school gathering with various religious leaders. When he declined the food, someone from another religious group approached him and said:

“I know why you didn’t eat. It’s Ramadan, isn’t it? You’re fasting.”

The brother replied yes. Interestingly, he had converted from that man’s own religion. The man then said something remarkable:

“Fasting is such a noble thing to do. It’s too bad our religion changed it over the years.”

Many religions have remnants of fasting—maybe avoiding certain drinks or foods—but the tradition has been diluted over time.

The “Criticism” of IslamPeople often criticize Islam by saying: “You Muslims are still practicing the same Islam from 1400 years ago.”

SubhanAllah. What a beautiful “criticism”! That’s exactly what we want—to follow the Islam practiced by the Prophet ﷺ and his companions.

Ramadan: A Month of Qur’an and Du’aIn the verses about Ramadan, there’s a powerful interjection. Between the verses on fasting, Allah ﷻ says:

“وَإِذَا سَأَلَكَ عِبَادِي عَنِّي فَإِنِّي قَرِيبٌ”

“And when My servant asks you concerning Me—indeed, I am near.”

“أُجِيبُ دَعْوَةَ الدَّاعِ إِذَا دَعَانِ”

“I respond to the du’a of the supplicant when he calls upon Me.”

Allah ﷻ will answer your du’a. Every single time.

The Power of Du’aYou might make du’a for a Cadillac Escalade. And either:

- You get it.

- You get something even better.

- Allah protects you from a harm you didn’t know about.

Even if your du’a isn’t answered in this life, it’s stored for the Hereafter.

The Prophet ﷺ told us: on the Day of Judgment, when people see the stored rewards of unanswered du’as, they will wish that none of their du’as had been answered in the dunya!

The Cost of Du’a and IntentionWhat does it cost to make du’a? Nothing.

What about making a good intention? Also nothing.

But the reward? If you make a sincere intention to do good, it’s recorded as if you did it. And if you actually do it? You get 10 times the reward.

Imagine the power of simply sitting down and making lofty intentions:

- “I want to build 1,000 masjids.”

- “I want to donate a billion dollars to da’wah.”

- “I want to bring a thousand people back to Allah.”

Even if only 1% of people fulfilled those intentions, our community would be transformed.

Don’t Let Others Deflate Your IntentionsSometimes when you make big intentions, someone will say, “That’ll never work. Be realistic.”

That kind of mindset deflates ambition. But the Sahaba didn’t think like that. In fact, the Battle of Badr happened during Ramadan. And what did they do? They fasted and fought.

The Prophet ﷺ made du’a:

“O Allah, if this group is destroyed, You will not be worshipped on Earth.”

Ramadan wasn’t just about fasting—it was about striving.

The Spectators and the ParticipantsMasajid are packed on:

- The first night of Ramadan.

- The last 10 nights.

These are the spectators—the ones watching from the sidelines. But the real participants are in the masjid every night. They push through, read Qur’an while others sip tea, and spend time feeding others—not just feeding themselves.

Shahr al-‘It’am vs. Shahr al-Ta’amRamadan is Shahr al-‘It’am—the month of feeding others. But many of us have made it Shahr al-Ta’am—the month of eating!

There’s so much pressure, especially on our sisters, to raise food quality. But is that the essence of Ramadan? Going to dinner parties? Eating more than usual?

The Prophet ﷺ performed i’tikaf in Ramadan—not social dinners. In his last Ramadan, he did 20 days of i’tikaf.

No More ExcusesPeople often say:

- “I can’t go to the masjid daily.”

But in Ramadan, they show up every night. - “I can’t pray Qiyam—it’s too hard.”

Yet during Ramadan, they wake up early for Suhoor and Qiyam. - “I can’t live without coffee or cigarettes.”

But in Ramadan? They go cold turkey from dawn to dusk.

The same goes for Qur’an. A person might read nothing all year, but in Ramadan they finish the entire Qur’an.

Training the SoulFasting trains the soul to obey Allah. You’re avoiding things normally halal—like food and drink—because Allah said so.

After Ramadan, avoiding haram becomes easier. Ramadan is about developing taqwa through spiritual training.

What Makes a Ramadan Unforgettable?Try to remember a Ramadan you’ll never forget. What made it unforgettable?

For most people, it’s tied to Taraweeh:

- A special imam.

- A deep focus.

- Consistent attendance.

But what if that imam isn’t there next year? Will you give up? No. You have to be the one who brings the focus—you extract the benefit, not wait for it.

Behind the Scenes: Life of the ImamLet me take you backstage—what is Ramadan like for the imam?

- After Fajr: Reviewing Qur’an while everyone else sleeps.

- Daytime: Resting intentionally to preserve energy for night prayers.

- Afternoon: More Qur’an review.

- Iftar: Light meal. If he eats too much, he can’t lead Taraweeh. He might literally vomit—no joke.

- Taraweeh: Complete concentration.

- Post-Taraweeh: Brief rest. Then the cycle continues.

Why? Because the Qur’an is his priority.

Be Like the ImamWhether you’re leading or not, you can live like the imam.

Let Ramadan become a month of:

- Qur’an

- Discipline

- Du’a

- Intention

- Ibadah

You can even aim to memorize 10 ajza’ this Ramadan. It’s not impossible. People have done it.

Final ThoughtsDon’t be the person who shows up at the airport and says, “I haven’t decided where to go yet.”

If you don’t know your destination, you’ll go nowhere.

Make your intention now. Plan your Ramadan today. Prioritize Qur’an and ibadah above all else. And with Allah’s help, you’ll make this Ramadan unforgettable.

Jazakum Allahu Khayran.

May Allah grant us all a truly epic Ramadan. Ameen.

Related:

The post How to Make this Ramadan Epic | Shaykh Muhammad Alshareef appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Germany grovels to Trump

A plan to train Gaza’s police will reinforce the occupation.

Scott Morrison accused of ‘deeply ill-informed’ attack on religious freedom after Islam speech

Former PM called for national register and accreditation for imams, sparking backlash from Muslim leaders

Get our breaking news email, free app or daily news podcast

Leading Islamic community groups have condemned Scott Morrison as “deeply ill-informed” and “dangerous” after the former prime minister demanded a national register and accreditation for imams, and expanding foreign interference frameworks to capture foreign links in religious institutions.

The former Liberal leader, speaking at an antisemitism conference in Jerusalem on Tuesday, claimed the measures were needed in the wake of the Isis-inspired Bondi terror shooting at a Hanukah event, which left 15 people dead. Morrison demanded a focus on “radicalised extremist Islam”, noting the two alleged Bondi shooters “were Australian-made” and demanding local Muslim bodies do more to stamp out hate.

Continue reading...Livestream: Trump's Board of Genocide

We talk to journalist Ahmed Al-Najjar in Gaza, where harsh conditions and Israeli attacks belie Davos claims that “war” is over. We discuss Trump’s “Board of Peace” and more.

[Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy

What does every new Imam need to know about being an imam? What do you do if you’re in a small community with minimal resources? How do you manage joining a new community, learning the ropes, and not biting off more than you can chew? In this episode, Sh. Mohammad Elshinawy shares his advice for new imams, community building, and reflections on his own imam experience.

Shaykh Mohammad Elshinawy is a Graduate of English Literature at Brooklyn College, NYC. He studied at College of Hadith at the Islamic University of Madinah and is a graduate and instructor of Islamic Studies at Mishkah University. He has translated major works for the International Islamic Publishing House, the Assembly of Muslim Jurists of America, and Mishkah University.

Related:

Don’t Take For Granted Your Community Imam I Sh. Furhan Zubairi

The Rise of the Scholarly Gig Economy and Fall of Community Development

The post [Podcast] The Parts of Being an Imam They Don’t Warn You About | Sh Mohammad Elshinawy appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Access denied: why Muslims worldwide are being ‘debanked’ | Oliver Bullough

Innocent people are being frozen out of basic banking services – and it all traces back to reforms rushed through after 9/11

Hamish Wilson lives a few miles away from me, in a cosy farmhouse in the damp hills of mid Wales. He makes good coffee, tells great stories and is an excellent host. Every summer, dozens of Somali guests visit Wilson’s farm as part of a wonderfully wholesome project set up to celebrate their nation’s culture, and to honour his father’s second world war service with a Somali comrade-in-arms.

Inadvertently, however, the project has revealed something else: a deep unfairness in today’s global financial system that not only threatens to ruin the Somalis’ holidays, but also excludes marginalised communities from global banking services on a huge scale.

Continue reading...Op-Ed: Bitterness Prolonged – A Short History Of The Somaliland Dispute

A longstanding aspirant statelet in the Horn of Africa shot to international attention this month when Israel announced its recognition of Somaliland, an otherwise unrecognized defacto state in northern Somalia that has existed since war engulfed the region in the 1990s. Because the issue of Somaliland secession is widely unknown to Muslims outside the region, this article will give a short summary of its history.

Colonial ContrastsSomalis constitute one of East Africa’s major ethnic groups, organized in clans and clan confederations and tracing their history back centuries in the region: major clan confederations included the Isaq, who dwell largely in Somaliland, the Hawiye in central Somalia around Mogadishu, the Rahanweyn in western Somalia, and the Darod, scattered around the region.

Today, Somalis are split across several countries beyond the eponymous Somalia. In part, this is a legacy of colonialism, when the British, French, and Italian empires waded into the Horn of Africa, where Somali clans and sultanates had already had a long history of opposition with Ethiopia. Djibouti became a French enclave; Somaliland and Kenya were British colonies; and the rest of Somalia was under Italian rule, with the exception of the Ogadenia region, named for the Ogaden clan within the Darod confederation that predominates in a region ruled by Ethiopia as its southeast province.

Italy’s defeat in the Second World War bequeathed most of Somalia to British rule, where it remained for a decade before official independence in 1960. The first British thrust into the region, some fifty years earlier, had been countered by the daring preacher and adventurer Mohamed Hassan, disparaged as the “Mad Mulla” for his twenty-year resistance. Hassan, from the Darod, had a mutual enmity with the Isaq confederation, which, unlike most others, Somalis do not remember him fondly. Somaliland had been a British colony for much longer than the rest of Somalia, and in fact was given independence a few days earlier in the summer of 1960.

Somalilweyn and its DiscontentsThat independence came after a long period of activism from Somali opposition parties, notably the Somali Youth League, which called for Somali independence and where support for the independence of the Somali peoples at large, not just those under British rule, was widespread in what became known as Somaliweyn or Greater Somalia.

A key roadblock to this idea was not just friction with neighbouring powers, notably an imperial Ethiopia whose rule of Ogadenia was widely unpopular, but also the balance of power within Somalia itself. Somaliland had become independent under its leading colonial politician, Ibrahim Egal, who was soon persuaded to join the rest of Somalia, for which he became prime minister. As a rule, Somaliland was a backwater, and much of the Isaq populace chafed; as early as 1961, there was a coup attempt that was speedily suppressed. In fact, as one of the few parliamentary democracies in 1960s Africa, Somalia’s first decade was generally marked by chaotic factionalism and in 1969 army commander Siad Barre led a coup; prime minister Egal, at the United States at the time, was imprisoned on his return as one of the many elites of his generation purged by the military regime.

Though Siad promised revolutionary change, siding at first with the Soviet Union in the Cold War against a Western-backed Ethiopia; what socioeconomic improvements he oversaw would be drowned by his own recourse to repression and corruption. A change in family law that contravened Islamic law in 1975 was an early flashpoint, and after a momentous war for Ogadenia in 1977-78 failed – where Somalia’s former Soviet allies switched sides to decisively join a newly communist Ethiopia – Siad’s dictatorship began to crumble from within. An early sign of the rupture came when Majerteen officers from Siad’s Darod confederation, led by Abdullahi Yusuf, attempted a coup immediately after the Ogadenia defeat; in its wake, Yusuf fled to Ethiopia, which supported him in a 1982 incursion into Somalia.

Corrosion under SiadThe 1982 campaign came even as Siad repressed another coup and purged his Isaq deputy, Ismail Abukar. Though Abukar was one of a number of cross-clan leaders imprisoned in this period, the Isaq clan in particular objected to Siad’s dictatorship; the previous year, a rebel Somali National Movement or Wadaniya had been founded by exiles in Britain. Though its membership was overwhelmingly Isaq – including former officials such as Ahmed Silanyo, police officers such as Jama Ghalib, army officers such as Abdulqadir Kosar, and clan leaders such as Yusuf Madar – the group importantly claimed to represent Somalia at large and, unlike its heirs today, rejected claims of secession.

Siad, by now bolstered with considerable weaponry by the United States, responded with an outsize cruelty that overwhelmingly targeted Isaq in the north and drove more into the insurgency’s ranks. By the late 1980s, an insurgency was in full swing and had overrun much of Somaliland. In response, in spring 1988, Siad’s son-in-law, Said Morgan, cut a deal with the Ethiopian regime to stop supporting one another’s insurgents before turning on Somaliland with savage ferocity.

The Harrowing of the North

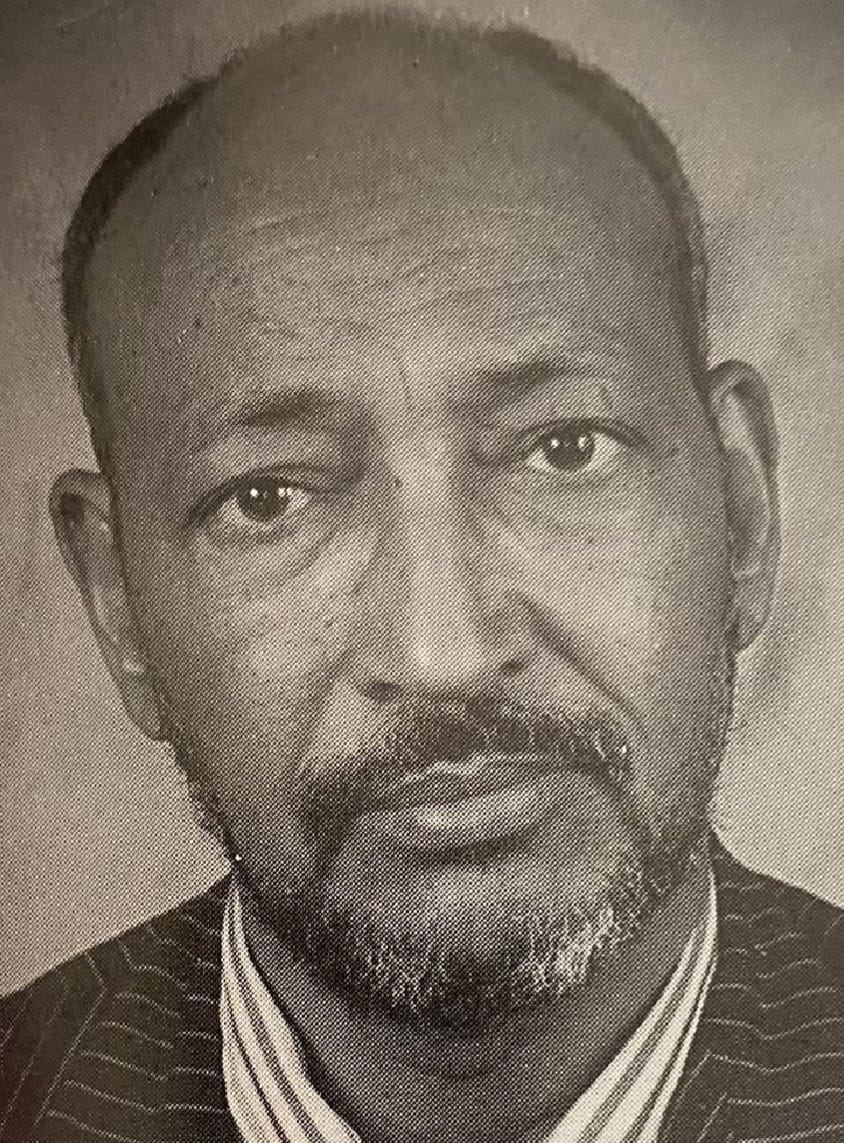

Said Morgan, the “Butcher of Hargeysa”

Morgan’s destruction of Somaliland carries parallels with the Iraqi Baath regime’s meantime harrowing of its own, Kurdish northland, during the same period. Like the Baath’s murderous governor-general, “Chemical” Ali Majid did with the Iraqi Kurds, there is no doubt that Morgan and his lieutenants saw Isaq as a fifth column to be bloodily crushed. As with supposed voice recordings of “Chemical Ali”, there are letters supposedly from Morgan that call for the elimination of the Isaq confederation; whether or not these are genuine, there is no question, and ample reliable evidence, that Morgan and his lieutenants were willing to butcher the population in droves. One particularly infamous call by an officer was to “kill everything but the crows” that came to feast on corpses. In the process, Morgan flattened Hargeysa and killed thousands, particularly through aerial bombardment.

As did Iraqi Kurdish opponents of the Baath regime, Siad’s opponents characterize this massacre as a genocide of the Isaq. It did, however, occur among a general narrowing of the regime where Siad, despite his rhetoric of shunning clan prejudice, narrowed his group of loyalists to not only his clan but his own family; it is no coincidence that his son-in-law, Morgan and son, Maslah Barre, were increasingly prominent in the army. The Isaq clan were the most brutalized but by no means the only victims; Siad had already frozen out the Majerteen clan within his own Darod confederation, and his favouritism also alienated much of the Darod’s Ogaden clan, whose army officers increasingly defected. Similarly, the major Hawiye confederation predominant in Mogadishu was increasingly disconsolate. By the early 1990s, a mixture of revolts and mutinies ousted Siad and helped plunge Somalia into what was unprecedentedly described as a “failed state”.

Freedom and Independence?In the process, the Wadaniya insurgents managed to capture Somaliland under the leadership of Abdirahman Tur; along with the Isaq confederation, the Darod Dhulbahante clan, led by such cooperative chieftains as Abdulghani Jama, now joined them. Wadaniya was more of a coalition than a fixed group, however, and its constituent camps began to fight for power. That this struggle was not as destructive as that of the remaining Somalia owed largely to the mediating role of chieftains and elders, who organized a number of conferences and elections.

Isaq chieftains such as Ibrahim Madar, son of the former Wadaniya leader Yusuf, were especially important and, with the rest of Somalia in disarray, began to push increasingly for secession. Somaliland was already de facto separate from the rest of Somalia, but the persistent agenda from the mid-1990s onward was for its recognition as a separate country. Since Somaliweyn had collapsed and Somalis were already split between other countries like Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Kenya, the argument ran, there was no point in Somaliland staying in a dysfunctional Somalia either. The moment also seemed propitious; in 1993, Eritrea broke away from Ethiopia after a long, difficult independence war.

Jama Ghalib

Even as the United States was leading a United Nations incursion into the rest of Somalia, Tur was removed in favour of the former Somalia prime minister Egal. Isaq commanders Tur and Ghalib, a former police inspector-general, opposed the secessionists and joined forces with Farah Aidid, Mogadishu’s preeminent commander who had first ousted Siad, and then the United States. However, in 1994-95, Somaliland “loyalists” of Egal managed to bloodily root out these Isaq dissidents in a series of battles at Hargeysa and Burao.

As a former prime minister of Mogadishu who had originally negotiated Somaliland’s addition to Somalia, Egal struggled to convince hardline separatists of his bona fides. Yet as his power increased, sidelining competitors by the late 1990s, he did indeed press toward a separatist agenda, and was even reported to have contacted the infamously anti-Muslim Israeli regime by offering cooperation against “Islamic radicalism”: this despite the fact that the original Wadaniya resistance against Siad had criticized his irreligiosity and dealt heavily in Islamic slogans, styling themselves “mujahids”; indeed, the Somaliland flag retains the Islamic shahadah. Somaliland was nonetheless seen favourably among foreigners wary of the conflict in remaining Somalia, and a considerable foreign lobby grew for its separation from Somalia and its recognition as an independent state. A year before his death in 2002, Egal held a referendum that opted for Somaliland’s secession as an independent state.

Somaliland, Puntland, and the Occupation of SomaliaHowever, secessionism was unpopular among the Dhulbahante who predominated in the Sool region of northern Somalia, between Somaliland and the coastal region of Puntland. Many Dhulbahante dissidents gravitated east toward Puntland, where Ethiopia’s former vassal Yusuf, had set up his own fiefdom and aimed to form Puntland as part of a federalist but united Somalia. When the American “war on terror” began, Puntland, and Yusuf more specifically, became a favoured client of the United States as a “counterterrorism” partner. In 2006, both the United States and Ethiopia invaded Somalia and ousted Mogadishu’s short-lived Islamist government, installing Yusuf in its place under a foreign occupation.

Yusuf’s place at the helm of an American-Ethiopian-backed regime in Mogadishu ensured that Puntland had Washington’s ear, but Somaliland’s major foreign lobby persistently argued for independence, while periodically cracking down against dissidents who favoured a united Somalia. The fact that the original 1980s Wadaniya resistance had rejected separatism was now conveniently forgotten; the fact that unionist Somalilanders such as Ghalib opposed the 2006 invasion ensured that they could be frozen out of the political elite with little repercussions.

On the other hand, even after Yusuf’s resignation, the Somali government and its Puntland wing attracted largely Dhulbahante dissidents in Sool who wanted their region to be separate from Somaliland and part of Somalia, either as part of Puntland or as a separate region. During the 2010s, when Somalia’s new federalist constitution was arranging new regions, the Sool region pressed its case: led by Ahmed Karash, the Sool region announced its loyalty to Somalia under the name “Khatumo” or finality, with support from both the central government in Mogadishu and the regional government in Puntland. There have been repeated clashes over this region, particularly Lasanod, since 2007.

Regional RivalriesThe replacement of relatively conciliatory Somaliland leaders such as Silanyo with hardline separatists like Musa Bihi, a former Wadaniya commander, helped harden this dispute. So did the attitudes of strongly unionist Somali leaders such as Mohamed Farmajo, who ruled Mogadishu in 2017-22, and Puntland leaders such as Said Deni, who was a rival to both Mogadishu and Hargeysa.

Regional rivalries also played into these disputes. A staunch centralist, Farmajo was long backed by Turkiye and Qatar, and opposed the United Arab Emirates, which was supporting a number of separatist actors in the region. He also tried to cultivate better ties with the new, similarly centralist Ethiopian ruler Abiy Ahmed. Ethiopia, which had a longstanding rivalry with Cairo, had meanwhile long found it convenient to play off the rivalry between Puntland and Somaliland, and the United States did the same. Saudi Arabia initially supported the United Arab Emirates in its dispute with Qatar, but has recently moved closer to Ankara, Cairo, and Doha.

The Somali government’s case was widely recognized abroad, but its own legitimacy was weakened by its reliance on the multipronged foreign occupation that had ousted the Islamists in 2006. Although a compromise brought back many Islamists, including the ousted former ruler Sharif Ahmed and his successor Hassan Mohamud, to the fold in 2009, cyclical squabbles over the makeup of the state and over an unpopular but essential foreign occupation have persisted. At their most extreme, Somali unionists resorted to the untrue claim that Shabaab, the main insurgent group, was a Somaliland agent, because many of its leaders were Isaq northerners. This was fantasy, but the claim’s very existence pointed to the difficulty of legitimation during a foreign occupation.

Road to DisgraceAfter returning to power to remove Farmajo, Mohamud managed to secure Lasanod and announced the new Sool-Khatumo region as a separate region, under Abdulqadir Firdhiye. However, Puntland leader Deni, closely affiliated with Abu Dhabi, threatened secession in 2024. And at the end of 2025, Israel, closely linked by now with the United Arab Emirates, followed up its support for secessionists in other Muslim countries by recognizing Somaliland.

In a move whose criticism within Somaliland was swiftly suppressed, Somaliland leader Abdirahman Irro welcomed Israeli foreign minister Gideon Saar and oversaw a generally shameless spree of welcomes for this new, supposedly groundbreaking relationship. Like other pro-Israel governments in the Muslim world, Hargeysa evidently supposes that ties to Israel will strengthen its international position, particularly with the United States. It is a disgraceful denouement to a political experiment that began with genuinely valid grievances but has morphed into an autocratically ruled fiefdom.

The fact is that the Somalia regime that ravaged Somaliland in the 1980s ceased to exist decades ago, and that the current Somaliland programme bears little resemblance to the Wadaniya insurgency of that period. Even as its government loudly cites the savagery of a long-extinct dictatorship in the 1980s to justify its separatism, Somaliland cracks down on dissidents and aligns itself with the most vicious regime of the 2020s.

[Disclaimer: this article reflects the views of the author, and not necessarily those of MuslimMatters; a non-profit organization that welcomes editorials with diverse political perspectives.]

Related:

– History of the Bosnia War [Part 1] – Thirty Years After Srebrenica

The post Op-Ed: Bitterness Prolonged – A Short History Of The Somaliland Dispute appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Far Away [Part 6] – Dragon Surveys His Domain

Lee Ayi reveals a disturbing secret, and Darius is pushed to demonstrate his abilities.

Read Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

* * *

Training GroundWhen the clothes were stacked in a hamper and the lines had been taken down, Lee Ayi said, “Wait here.” She disappeared into the house and returned with a wooden training dao that I had not known existed, as well as my own spear.

I froze, remembering my father’s ruthless training. What was this? Like brother, like sister? The blood rushed to my head, and my face turned hot. I was not that little boy anymore, and even my father had stopped abusing me eventually. My entire body tensed. In that moment, I could hear the cowbells as the animals grazed in the far field. I smelled the faint, sweet musk of the safflowers, and could feel my own heartbeat in the wound on my shoulder.

Lee Ayi handed me the weapons. “Yong trained you, yes?”

I stood mute, one weapon hanging limply in each hand.

“You don’t have to answer. I can see it in every step you take. Even the way you work. Your balance, poise and economy of motion. The subtle flourishes you add when sweeping the floor. The way you shift your weight. Well, my father trained me as well, though not as thoroughly as Yong.”

I swallowed. “Okay, so?” The words came out dry and hoarse.

She waved to the circle of clear earth where the clotheslines had hung. “This is my training ground. I need to practice.” She clenched a fist, a gesture so unlike her that I shifted my weight to the back foot. “It’s part of me,” she continued. “It’s in my blood. But Husband does not approve of martial arts, nor any form of violence. So every Friday I wait until he goes to Jum’ah and I practice alone. This is my secret. Maybe the farmworkers see but they mind their own business. But you are here now. Will you keep my secret?”

“And what do you need me to do?”

“What?” She shook her head. “Nothing. Just keep my secret. Will you do that?”

A Negotiation“What is the real reason Ma Shushu did not take me to town?”

Lee Ayi tipped her head back, regarding me. A slow smile appeared. “You’re a negotiator, eh? My brother taught you many things.” The smile vanished, replaced by a serious expression. “Can we just say that he wants your shoulder to heal, and leave it at that?”

“Is that the truth?”

“Part of it.”

Lee Ayi looked down, spotted a small stone that had found its way into her training space, picked it up and chucked it. Then she stood straight and looked me in the eye. “Your Ma Shushu does not want the Shahs to know you exist.”

I frowned. I didn’t know what answer I had expected, but this wasn’t it. “Why?”

“Nur was Shah Zheng’s only daughter. He married three wives, but he apparently lost his fertility and could not sire another child. He is an old man now, and you, as his grandson, are his only surviving descendant. You are thus heir to the family fortune. But Zheng has a younger brother, Osman. He now runs the family business in all but name. He is a ruthless, unprincipled man. Husband is afraid that if Osman knew about you, he would kill you.”

The thought that my mother’s family, instead of being happy to know me, might want to kill me, made me feel empty inside. I walked to the washing basin and sat on the stone rim, putting my chin in my hand.

“I’m sorry,” Lee Ayi said. When I did not reply, she said, “And my secret?”

I waved to her to go ahead and practice.

A Single StepShe began with empty hands, and at first I barely watched.

My thoughts were still tangled in what she had told me about the Shahs, about my mother’s family and the danger attached to my very existence. I sat on the stone rim of the washing basin, my chin in my hand, staring at nothing in particular while Lee Ayi stepped into the cleared circle of earth.

Her movements were confident enough, practiced, familiar. She knew the basic Five Animals stances, strikes and forms. Tiger, Crane, Snake, Praying Mantis, Dragon. The transitions were there, but sometimes incomplete. One time she flowed from one posture into the next and forgot the intervening strike entirely, leaving a small emptiness in the form that my eye snagged on instinctively. Her stances were serviceable but shallow, her steps sometimes too short, as if she were reluctant to fully commit her weight.

I watched without comment.

When she stretched a hand and requested the wooden dao, and I tossed it to her, something changed. Her posture straightened. She turned her hips fully into the cuts, using her whole body rather than her arms alone. The blade whistled softly as it passed through the air. She was not elegant, and her repertoire was limited. But she was effective. There was intention behind every strike.

With the spear, however, she struggled. Her grip was too far down toward the end, and her hands did not slide smoothly enough on the wood as she changed grips. She overextended on slashes and used her muscles to slow the spear down at the end of the movement, rather than using her body to bounce it back or whip it around, which resulted in slow recoveries. A couple of times I winced involuntarily. My father would have beaten me if I’d done that.

When she finished, she stood in the middle of the circle, hands on her thighs, breathing hard. Sweat darkened the collar of her tunic and ran down her temples.

“Well?” she asked. “What do you think?”

I gave a half shrug. “You’re strong. And fit.”

She gave me a sharp look. “That’s not an answer.”

“You’re pretty good with the dao.”

“And the rest?”

I threw up my hands and blurted, “Why are you asking me? I’m just a kid.”

She snorted. “You are that. But you know more than you reveal.” She wiped her face with her sleeve and regarded me steadily. “Show me something of your own.”

I felt my shoulder throb in warning. “What do you mean?”

“Something small,” she said. “One form. Slowly. We can’t risk you opening that cut.”

I should have refused. Every lesson my father had drilled into me screamed that this was a mistake. We kept our skills secret, we did not show them off. But something in her gaze held me there, not challenging, not pleading, simply certain. And anyway, she was family.

I stepped into the circle.

Dragon Surveys His DomainThe earth felt different beneath my feet, packed and bare. I took one wide step forward and dropped into a deep stance, sweeping my hands down to one hip, then drawing them up in a wide arc. The movement finished with my hands snapping back into a tight guard, balanced and ready.

I straightened and saluted, one fist against an open palm. The hand of war and the hand of peace.

“Dragon surveys his domain,” I said.

Lee Ayi stared at me. Her face had gone very still. “You are highly trained.”

I did not answer.

She extended the dao, handle toward me. I pursed my lips and grimaced. “You know I’m injured.”

“Your left shoulder is injured. Use your right hand.”

My nostrils widened as I inhaled deeply, then let it out. “Why?”

“I want to see.” Her tone was deadly serious.

I swallowed. “Only a little.” I took the dao and twirled it easily in my hand, closing my eyes, warming up my muscles.

I saluted with the dao, raising it above my forehead and parallel to the ground, then stepped slowly to my left, bringing the dao up in a number one roof block that flowed into a slash to the neck of an imaginary enemy. I continued with this slow motion dance, reaching around with my hand and pulling, slashing, then spinning away into a thrust that was only a feint that turned into another slash.

I stopped and faced Lee Ayi. “Crane circles the hill.”

She regarded me solemnly. “You killed two men.”

Shock widened my eyes as I remembered the two robbers I’d killed and buried in the peanut field. But how could she know? My brain raced, then I realized – feeling like an utter fool – that she meant the movement I had just done. It was a form, a prearranged sequence in which I killed two imaginary opponents.

“Yes.”

She gestured. “More.”

I twisted my mouth to one side. “Why?”

“My father taught me that sequence, but I forgot it. I want to see more.”

River FlowI let out a breath that was almost a sigh. Then I took a long diagonal shuffle step one way then the other, attacking with a series of slashes from different angles as my feet danced lightly across the dirt.

As I moved, I fell into River Flow. There were no more cowbells, no afternoon sun heating my face. No Lee Ayi, even. Without plan or awareness, my movements sped up. I leaped up and came over the top with a thrust, but it was a feint that pivoted into a cutting diagonal slash at the last instant. My body had missed this. I was a flame of fire, my movements too fast for an untrained eye to follow. The dao was a part of me. Anything I could envision, I could do.

Many mediocre fighters fought with nothing but the blade, but I was better trained than that, and I threw kicks that snapped out and back, punches that made my wounded shoulder ache, and hits with the pommel of the sword that flowed into elbow strikes that flowed into short-range slashes and thrusts. Never was I out of balance, never did I hesitate or falter.

The dao was a shadow that darted behind my back and around my head, surged high and dropped low, and struck from unexpected angles. In River Flow my parents were not dead, and Far Away was not lost. There was only the movement and my imaginary enemies, and I was in harmony with them. When they pushed forward I slipped to the side to let them pass. When the enemy charged I parried and let him run into the point of my sword. When he slashed I side stepped and matched his slash, cutting along the length of his arm. There was no opposition, no clash. My father had repeated this many times: “The enemy tells you how to kill him.”

I forgot that my aunt was there. My movements became more dramatic. I moved as I used to in my solitary practice sessions, after my father had gone. At one point I did a forward somersault in the air, coming down with a vertical slash, which reversed into an upward slash intended to catch the enemy’s hand. These were movements my father could no longer perform himself, but had coached me through, and some were movements I myself had invented when I practiced alone, after he had gone.

I stopped when the pain in my shoulder reminded me where I was. I stood in the circle, breathing deeply but comfortably. I did not know how much time had passed. Perhaps enough to lower a bucket into the well twice and pull it back up.

Turning, I saw Lee Ayi’s face. She looked stricken. I knew immediately I had done the wrong thing. Stepping forward, I bowed deeply and offered her the sword with both hands, the edge facing me.

Not GentleShe snatched the dao out of my hands. Her face was pale, her jaw tight. “You shame me.”

I looked away, my gaze alighting on the tall elms that sheltered the house. “That was not my intention.”

“I know.” She exhaled once, sharply. “I have never witnessed such skill. Not even from Cai Lee, and he was a grandmaster. How did you learn that?”

I met her eyes. My gaze was uncompromising. “My father trained me from the time I could walk. He was not gentle.”

“Fathers are sometimes not gentle. That doesn’t mean they -”

“Haven’t you seen my scars?” I nearly shouted. My nostrils flared as I yanked my sleeves up, showing her the many scars on my arms, from cuts my father had given me with the spear, the wooden dao and even the live dao. Some were pale and faded, while others were pink and raised.

She blinked. “I thought from the rough peanut vines, or the hoe.”

I pulled my shirt up and threw it on the ground. “And these?” My stomach and chest also bore long scars.

Her anger was gone, replaced by dismay. “Yong did that?”

“I told you. He was not gentle.”

Her lower lip trembled, and a pair of tears rolled down her dusty cheeks, leaving clean tracks. “I’m sorry.”

I didn’t know what to say, so I said nothing.

“Your cut has reopened.”

I looked at my shoulder and indeed she was right. The bandage was stained deep red.

Gently, my aunt took my hand, led me into the house, washed my wound and re-bandaged it.

Gently, my aunt took my hand, led me into the house, washed my wound and re-bandaged it.

“You rest,” she said. “I will finish today’s housework. Don’t tell Husband about what we did today. Or about your wound.” She began to leave, then turned and said, “I’m sorry.”

When she was gone I lay in my bed, wishing that Far Away was here to cuddle up next to me and purr. I knew I had hurt Lee Ayi in more ways than one. I felt like my past was a heavy chain around my neck. It would always be there. I would never be free.