Aggregator

Livestream: Mossad not hiding role in Iran violence

We talk to Mohammad Marandi, cover resistance in Gaza, UK hunger strikes, pro-Palestine backlash in Australia and much more.

[Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid

Muslims swept off the street by ICE, Somalis in Minnesota targeted by racism from the President of America, Palestinian activists illegally detained: post-Trump America is a hellish dystopia… yet one that many Muslims voted for.

In this episode of the MuslimMatters Podcast, Zainab bint Younus speaks to Imam Dawud Walid about the political and cultural pendulum swinging to the right after the leftist allyship of the 2010s, and the phenomenon of Muslims voting for Trump in the last election. She asks him about his book “Towards Sacred Activism” and what priorities Muslims need to keep in mind before choosing to engage with or seek allyship with political and cultural groups in the West. Are Muslims meant to be right-wing or left-wing? Tune into this episode for a deep dive into this contentious discussion.

Imam Dawud Walid is currently the Executive Director of CAIR-Michigan, member of the Imams Council of Michigan, and advisory board member of Muslim Endorsement Council (MEC) which is a national endorsement and support organization for Islamic chaplaincy. Imam Dawud has ijazaat in various disciplines of the Islamic sciences, has served an imam for many years, in addition to writing several books, authoring essays, and speaking at multiple institutions around the world.

Related:Podcast: Priorities and Protest | On Muslim Activism with Shaykhs Dawud Walid and Omar Suleiman

The post [Podcast] Should Muslims Ally with Conservatives or Progressives? | Imam Dawud Walid appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Iron Principle Under Pressure: A Profile Of Naledi Pandor

The principal role for which Naledi Pandor of South Africa is known is politics, but her principal interest lies in education. During the final year of her career in 2024, the septuagenarian foreign minister of South Africa gave an education in principled politics with perhaps the most concrete step of any government minister against Israel’s assault on Palestine when she took them to an international court for genocide.

There were personal costs to pay, of course, given the ferocity of Zionist propaganda that has accompanied the genocide. Most recently, in November 202,5 her visa to the United States was revoked in an extraordinarily petty move, which was nonetheless celebrated by Zionist organizations, many of which had spent months attacking both South Africa in general and her in particular for having had the temerity to challenge their bloody assault on Palestine.

But for Pandor, the vindication of being on the right side of history was well worth it. Speaking at Ottawa during a whirlwind trip through Canada just days before the cancellation of her visa, she described the feeling when, after months of personal attacks, professional snubs, and outright mistreatment by both local rivals and foreign peers, her case was found to have been valid all along: “Thanks be to Allah, it’s a wonderful feeling.”

Not that there was any let-up in the urgency of the Palestinian cause, of course. With the genocide still afoot, she emphasized the importance of civil society and mass, organized international solidarity. Palestine’s plight required, she said, that its supporters “build a united global front” in support. This front can not afford parochialism, sectarianism, tribalism, and hatred.

BackgroundPandor grew up amid the downtrodden black majority in apartheid South Africa in a family with both educational and political roots. Her grandfather, Zachariah Matthews, was a professor renowned throughout Africa, who was exiled from his homeland after opposing apartheid in 1956 and became a diplomat for the newly independent Botswana before he passed away. Though he was also exiled, Zachariah’s son Joseph Matthews, Pandor’s father, ended up taking a different route: after apartheid ended, he left his father’s party, though he served a few years as minister in charge of police in a subsequent coalition cabinet. By contrast, Pandor, like her grandfather, spent her political career in the African National Congress, which has ruled South Africa for the past three decades.

The African Congress’s rise to power in 1994 came at the end of several generations’ worth of struggle, where they were the main, banned party representing South Africa’s downtrodden majority against the apartheid regime. Their leader, Nelson Mandela, is renowned in anticolonial circles for, among other things, his unfettered solidarity with Palestine, famously remarking, “We know too well that our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians.” It was this internationalist solidarity that Pandor inherited; speaking at an event arranged by the Justice for All organization, she emphasized the need for human dignity and freedom across borders – highlighting, along with Palestine, the cases of Rohingya, Uyghurs, and Kashmiris as oppressed people deprived of their rights.

From South African Apartheid to Israeli Genocide

“Pandor stressed the importance of civil society as nimbler, more flexible form of activism than reliance on officialdom” [PC: Al Jazeera]

Israel’s supremacist regime over Palestinians has often been likened to apartheid; Pandor recounted the similarities in militarized townships, forcibly separated places for different races, and the seizure of land for European settlers. In some respects, the current situation is even more ludicrous: where the apartheid regime in South Africa handpicked puppets to impose on the majority black population, today Tony Blair, the former British prime minister and notorious neoconservative ideologue, is being trotted out as a prospective viceroy for a Gaza that does not want him.But Pandor also emphasized certain key differences. In South Africa’s minority rule, the majority workers in unions were able to organize and protest on account of their importance to the South African economy, thus pressuring the same apartheid regime that deprived them. This is not applicable to Palestine, especially under the current genocide, where the role of international solidarity becomes that much more important.

Pandor stressed the importance of civil society as nimbler, more flexible form of activism than reliance on officialdom: civil society can also afford to stick to its principles in ways that officialdom may not. In taking political stances on principle, she remarked, “For some of us, we are there for freedom, for others we are there for the selfie – and actions will tell which one [is which].”

As an experienced diplomat, she lamented the limitations of even multilateral international bodies and particularly urged the reform of United Nations institutions to break free of the control of the major powers: “It is tragic that the body we rely on for peace and security,” she said, was dominated by five member states more responsible between them for global insecurity and war than the others put together.

The role of principled activism was therefore paramount for Pandor, who quoted Mandela’s advice to youth: “Be a person who makes trouble, but make good trouble.”

South Africa’s Fight for Justice, Home and AbroadFighting for a just cause dovetailed neatly with Pandor’s understanding of Islam, to which she converted earlier in life. The African Congress had a considerable amount of support among South Africa’s Muslim minorities, many of whom had been engaged in the campaign against apartheid. For Pandor, faith in Allah enabled her to withstand frequent barbed attacks from political opponents. These could go from sweeping bigotry, as evidenced by much of the attacks on South Africa’s current government in recent years, to the pettily personal: she drily recounted how rivals attacked a slight British inflection in her accent, having studied and taught in Britain in her youth.

Education was Pandor’s first job, and after a stint leading South Africa’s equivalent of a senate, the first woman to do so, she held a number of ministries largely related to educational advancement. She also served a brief stint as interior minister, and ended her ministerial career with five years as South Africa’s foreign minister. As a veteran politician well-versed in the cut and thrust of power, her initiative in a principled cause meant that much more. So too did her emphasis on the importance of civil society, something located well outside the realm of the corridors of power.

Since it threw off apartheid in the 1990s, South Africa has generally been seen as a leader on the African continent and is often catalogued among rising states in the international system. With that system having long been dominated by first colonial, and then Cold War superpowers’ competition, Pandor emphasized the importance of this moment in history: when these “Global Northern” powers, who have dominated international relations for centuries, are in flux. It was a huge opportunity, she said, for the “Global South” to reconfigure international relations to a more equitable keel.

It was only a few days later, after her trip to Canada, that Pandor found that her visa to travel to the United States had been revoked. This stemmed partly from a general hostility toward South Africa by the United States, especially during Donald Trump’s current reign, where far-right activists regularly and speciously claim that Pretoria’s anti-apartheid measures discriminate against the white minority.

This reached such a stage that Trump personally berated South African leader Cyril Ramaphosa for this fictitious oppression and offered asylum to white South Africans fleeing the country, a ludicrous proposition that even baffled many of its intended beneficiaries. And it also stemmed from a linked Zionist campaign against South Africa, which is accused of being in cahoots with Hamas to malign the Israeli state. Pandor, the highest-profile Muslim minister, a black veteran of the anti-apartheid movement, and the lady who took Israel to court, was a central target.

Throughout it all, the South African has kept a dry wit, a stiff upper lip, and an iron will. “Remain engaged until freedom is won,” she said at Ottawa. “That is all.”

Related:

– Who’s Afraid Of Dr Naledi Pandor? – Zionist Panic and a Visa Revoked

– When News Becomes Propaganda: Gaza, Genocide, And The Media

The post Iron Principle Under Pressure: A Profile Of Naledi Pandor appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

New Year’s rituals in Gaza transformed

Far Away [Part 5] – There Is Only Work

A day of prayer, work, and long-buried family truths ends with Darius left behind, wondering what he is not being told.

Read Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

* * *

Darius’s First PrayerAs ordered, I rose at dawn without prompting – I could almost hear my own cow back home calling, wanting to be milked – and dressed to tend to the morning duties.

As I walked toward the door, Haaris took my hand to stop me. “Not yet,” he said. “We have to pray Fajr.”

I had no idea what he was talking about, but Zihan Ma entered from the front door, sleepy-eyed, but with his face and beard dripping water. He said gently, “Make wudu’. Haaris, show him how.”

Haaris led me out into the cold, to the outhouse. It was a long walk, as the outhouse was on the edge of the property next to the safflower fields, in an area where the land sloped downhill. There was a hedge planted in front of it, shielding it from view, and I saw that there were actually two of them. Haaris explained that it was a twin-pit system, in which one pit was allowed to decompose while the other was in use. When fully decomposed, it would be emptied and the waste would fertilize the fields. The latrines stank a bit, of course, and flies buzzed about. That was normal.

We relieved ourselves, then walked back to the house. On the western side of the house there was an open space with clothes lines strung up. The well was there, surrounded by a circle of flat stones, and with a large stone basin beside it. Using a ladle to scoop the water, Haaris showed me how to wash my hands, mouth, nose, face, arms, hair, ears and feet.

“You do this every morning?” I was amazed, for I had typically not bathed more than once every three or four days.

“More than that,” Haaris said.

Inside, a large bamboo fiber mat had been laid down in the living room. We arranged ourselves in a formation, with Ma Shushu in front, myself and Haaris behind him, and Lee Ayi behind us. I understood that we were about to begin a religious ritual of some kind. Lee Ayi had assured me that they did not pray to statues, and that was obvious, as there was no statue in sight. According to her, they prayed to Allah, an eternal, all-powerful being.

“What if I am not yet ready to participate in this ritual?” I asked.

Ma Shushu gazed at me solemnly. “Nothing will happen. There is no compulsion in religion. You will still be a part of the family.”

I remembered my father’s words: “The only one to worship is Allah.” He had not explained, but my heart told me that if he were here, he would not object to this ritual, even if he himself did not participate. I exhaled, feeling my chest relax. “I will pray with you. But I don’t know what to do.”

“Just imitate Haaris’s movements for now. We will teach you the words later.”

I raised my hands as Haaris did, and Ma Shushu began to recite. The words were foreign, but his voice was deep and pleasant, and the rhythm of the chanting was hypnotic. I felt myself falling into River Flow, just as I did when practicing Five Animals. We bowed, stood, prostrated, sat, prostrated, and stood again. At one point we looked right and left, and I did not know the prayer was finished until Ma Shushu turned in his place and sat cross-legged.

“How do you feel?” he asked me.

I felt close to tears, was the truth. All those times I had stopped and watched the people in the temple, and felt envious of them in spite of their stupidity, and felt a pull to join them – now I understood why. I felt small and humble, but not humiliated, and certainly not stupid. Rather I felt elevated, not in a literal sense, but as if my heart had grown in my chest. I could not express any of this, and in the end I only said, “I feel calm.”

Ma Shushu nodded. “That is a good way to feel.”

Women’s WorkI was prepared to go out and start the farmwork, but Ma Shushu stopped me. “Not yet. Your shoulder is not ready. Only light housework for now.”

First I swept the entire house. Then Lee Ayi set me to work at the low table near the window, where the morning light poured in, deep and yellow. I sifted a huge sack of rice to remove small stones, and when that was done I shelled peanuts into a clay bowl, the dry skins crackling softly between my fingers. I worked quickly but methodically, not missing anything. My shoulder still ached, but the work was slow and did not strain it.

The scent of the peanuts reminded me of home, and I found myself missing Far Away and Lady Two. My poor cat. Where was he now? Running from house to house at night, pawing through the garbage for a scrap? A dairy cow was valuable, someone would always care for her. But a stray cat with no parents who loved him, no home, no job? They would throw stones and chase him away. I sighed.

“What’s wrong?” Lee Ayi asked as she rinsed a pile of vegetables.

I shook my head, saying nothing.

Outside, I could hear goats bleating and the dull thump of hooves, the steady noises of a working farm that went on without me.

Lee Ayi moved quietly in and of the room, taking the vegetables outside to dry on woven trays, and lifting lids to check simmering pots. Every so often she glanced at me, not to hurry me, but to be sure I was not favoring the wounded arm too much.

“You work like your father,” she said at last.

I looked up, startled. “Is that good or bad?”

She smiled faintly. “Both.”

She sat across from me and began stripping safflower petals from their heads, her fingers quick and practiced. The petals fell into a shallow basket like small flames.

“I feel bad,” I said, “that I am doing women’s work, while Haaris is outside by himself.”

Lee Ayi gave an annoyed click with her tongue. “There is no men’s work and women’s work. There is only work. All work holds dignity. A cook and a floor sweeper are no less dignified than a horse trainer or an army general. As Muslims, we serve Allah by serving humanity. When you work to benefit others you are working for Allah, and that is the highest calling.”

This was a foreign concept to me. What did humanity have to do with me? My father had never believed in serving anyone nor benefitting anyone except himself, me and my mother. Perhaps a compromise would be to understand it as service to family. By serving this family, I served Allah. I could accept that.

Highway Robbery“Yong was always restless,” Lee Ayi said, as if reading my mind. “Even as a boy. Cai Lee tried to beat it out of him. It did not work. The harder Father pushed, the more Yong pushed back.”

I said nothing. I had never heard my father spoken of as a child.

“He had no patience for books,” she went on. “Nor for rules. The only things that ever held his attention were fighting and gambling. Martial skill came to him as easily as breathing. Gambling too. He was very lucky. Or perhaps very cursed.”

Her mouth tightened briefly, then relaxed again.

“He never cared for religion. Not even a little. When he began drinking as a teenager, Father said enough was enough. He cast him out. No food, no money, no place by the hearth.”

She did not look at me as she said this, but at the safflower petals.

“I used to meet him in secret,” she said quietly. “I would bring him steamed buns, or rice wrapped in cloth. A few coins. He always said he would pay me back one day.”

She gave a short, humorless laugh. “He never did.”

I would have smiled at the ridiculous notion of my father paying anyone back for anything, but the image of him as a hungry youth wandering the roads sat badly in my chest. As my father had lived, so had I as well. Was that the curse my aunt spoke of? Would I pass the same curse on to my own children?

“One day,” she continued, “Yong came upon a carriage stopped on the road, surrounded by three thieves. Highwaymen. Atop the carriage sat a noble Hui family, the Shahs. Among them was their daughter, Shah Nur. She was sixteen years old and beautiful. Yong fell in love at first sight.”

I froze, watching Lee Ayi intently. Shah Nur was my mother. I had never heard this story before, nor did I know anything about my mother’s family.

Lee Ayi went on: “I suspect if not for the beauty of Shah Nur, Yong would not have interfered. But he took it upon himself to attack the highwaymen. He carried nothing but a staff, while the highwaymen were armed with swords. Yet Yong killed one of the robbers in seconds. Seeing this, your grandfather, Shah Zheng, dismounted and joined in, taking the dead robber’s sword. Between them they drove the other two off.”

It was easy for me to imagine my father doing that. In my mind I could picture the entire battle, and could describe precisely what moves Yong had performed. This was the only incident I’d ever heard of in which my father’s fighting skills had been used to help someone. I felt proud of him.

The Shahs“The Shahs,” Lee Ayi went on, “are descended from Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas, the companion of the Prophet, peace be upon him, who brought Islam to our land. They are the most noble of us all, and the most wealthy, as they organize and finance huge caravans that carry goods from here to India, Persia and Turkey.”

“I saw a caravan once,” I enthused, pleased to be able to tell Lee Ayi something she did not know. “We passed it on the road from my family’s town to the city. It had fifty horse-drawn wagons, can you believe it? They were loaded up with textiles, spices, armor, pistachios, and other things I could not see. It was guarded by many men. I never thought there could be so many armed men outside of the army.”

“Did the wagons bear an emblem of a mountain peak surrounded by five stars?”

“Yes!” I grinned at her. “How did you know?”

“Those wagons belong to the Five Stars Trading Company. That is the Shah family’s company.”

I gaped. “One family owns all of that?”

“And much more. Anyway, Shah Zhen rewarded Yong well for saving their lives. It was more money than he had ever seen. It happened, however, that as he had fallen in love with Nur, she too was captivated by him. For the Shah family, such a match was out of the question. Yong was nominally Muslim, but he was a nobody, a lout. So Yong met with Nur secretly and convinced her to leave with him. It was madness. But she was young and brave, and ready for an adventure. They used the money to buy a farm in another town. They disappeared.”

She resumed stripping petals.

“After you were born, Yong came back only once, alone, to give us the news. But the Shah family had never stopped looking for Nur. They put a price on Yong’s head. He knew if he stayed, he would bring danger to us all. So he left again and never returned. We knew that you existed, but that was all.”

I set the last peanut into the bowl and rubbed my fingers together, brushing away the skins. A multitude of thoughts swirled in my head. I didn’t think my poor mother had gotten the adventure she dreamed of. My father had never been cruel to her, had never beat her, but neither had he been the loving husband she must have hoped for. He had a temper, he shouted at times, he went to town to drink and gamble, and he was in and out of jail as far back as I could remember. Our farmhouse was decrepit and non-productive, and we had been very poor. And now Shah Nur, daughter of a great and noble family, was buried in a small flower-lined plot behind an abandoned, broken-down farmhouse.

I must have been silent for a long time, because I found Lee Ayi beside me, rubbing my shoulder. “It’s okay,” she said. “What’s done is done. Your mother is with Allah, just as we all will be one day. The best thing you can do is remember her love for you. That is her legacy.”

I nodded. Feeling the need to defend Yong Lee, I said, “My father did better in the end. He changed.”

Lee Ayi nodded. “I believe it. He joined the army to provide for you. That was an act of love.”

My lower lip trembled at that, but I managed to stifle it.

DhuhrAt that moment, Ma Shushu came in from outside, his arms and face again dripping water. “Time for Dhuhr,” he said simply.

We laid out the mats. Lee Ayi adjusted my cushion so I would not strain my shoulder. Haaris was still out in the fields, his voice carrying faintly as he called to the animals.

“What about Haaris?” I asked.

“He is tending to the animals,” Ma Shushu said. “He will pray on his own.”

I felt a flush of heat rise up my neck. The boy was outside working while I was in here, clean and sheltered, shucking peanuts and sifting rocks out of rice. I reminded myself of Lee Ayi’s words: All work holds dignity.

When the prayer was over, Ma Shushu – seeing my obvious embarrassment – said, “You will be back in the fields soon enough. Do not borrow tomorrow’s pride today.”

After prayer, we ate a simple meal. Rice, greens, a little salted fish. I ate slowly, forcing myself to be mindful.

Lee Ayi made a plate and asked me to take it out to Haaris. I found him in a wide, grassy field on the other side of the outhouses. I hadn’t even known this field existed. The scent of the grass was rich in my nostrils. Haaris sat on a boulder, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, holding a bamboo switch and watching the cows, donkeys, and goats as they grazed. His boots were dirty, and he looked tired. He accepted the plate eagerly and began to devour it.

“Watch the baby goat.” He indicated with the chopsticks. “It keeps trying to headbutt the calf.”

I squeezed in next to him on the boulder and watched. The goat was more than a baby – maybe six months old, I would guess, though my eye was unpracticed – while the cow’s calf was younger but much bigger. As I watched, the goat bleated loudly, reared up on its hind legs and aimed its forehead at the calf, which was busy grazing. At the last instant the calf moved its head to the side and the goat missed. Haaris laughed out loud, spitting a bite of green beans.

I smiled as well. “The goat is a fighter.”

“Say ma sha-Allah.”

“What is that?”

“Oh, it’s like, this is something good that Allah made.”

“Repeat it.”

Haaris repeated the phrase, and I did my best to pronounce it.

“I’d better get back,” I said.

“I’ll see you soon,” Haaris promised. “We have studies.”

StudiesI changed the sheets on the beds then took the food scraps – vegetable peels and such – out to the compost pile. Outside, the sounds of the farm went on. Inside, the day settled around me like a garment I was still learning how to wear.

A few hours later Haaris and I sat on woven mats in Ma Shushu’s study, the afternoon light slanting in through the window and laying a pale rectangle across the floor. A low desk stood before him, its surface worn smooth, with a stack of books neatly arranged at one corner. Haaris sat cross-legged beside me, already alert, his back straight and his hands folded in his lap as if lessons were a form of prayer in themselves.

Ma Shushu began with numbers.

He drew figures in charcoal on a wooden board, simple at first. Counting, grouping, dividing. Haaris answered quickly, eager to please. I was slower, unused to putting numbers to paper, but the logic of it came easily enough. When Ma Shushu shifted from grain tallies to weights and measures, I leaned forward without realizing it. This was useful knowledge. Real knowledge. The kind that kept accounts honest and prevented quarrels.

“Math is justice,” Ma Shushu said, tapping the board once. “If you cannot count, someone else will count for you, and it won’t be in your favor.”

After that came reading and writing. Haaris fetched brushes and ink while Ma Shushu laid out a sheet of paper. He wrote a single character and explained its strokes, the order, the balance. Haaris practiced carefully, tongue caught between his teeth. When it was my turn, my hand felt clumsy around the brush, but Ma Shushu corrected my grip without comment and had me try again.

“Slow,” he said. “Meaning comes from care.”

My father had taught me to read and write by drawing characters in the dirt, using the wooden training dao. I had literally grown up writing with a sword. However, I was not used to the brush, or the small scale. Once my hand became accustomed to the grip, and I learned to ease the pressure and make everything smaller, my hand began to flow. The brush whispered across the page.

“Have you done this before?” Ma Shushu asked. “You pick it up fast.”

“My father taught me using a – “ I stopped myself. “A stick.”

“A stick?” Ma Shushu sounded offended. He shrugged. “Well. Not everyone has resources.”

I stiffened for a moment, not sure if my father was being criticised. Then I took a breath and relaxed. I did not want to see my father and Zihan Ma as opposites or opponents. My father’s lessons in Five Animals had literally saved my life. Once, at the town fair, I had seen a relay race, where the teammates passed a red ribbon from one to the next. I imagined my father passing a ribbon on to Zihan Ma. I was that ribbon. That was my hope, anyway.

When the ink was set aside and the brushes rinsed, Ma Shushu poured water into three small cups. He drank first, then gestured for us to do the same.

“Now,” he said, “we speak of deen.”

Haaris shifted closer, his expression changing. This was his favorite part, I could tell.

Ma Shushu did not open a book. He rested his hands on his knees and looked at us, first at Haaris, then at me.

“All of it begins with tawheed,” he said. “The Oneness of Allah.”

He did not raise his voice or dramatize the words. He spoke as if stating a fact as simple as the sun rising in the east.

“There is one Creator. Not many. Nor should anything else in the creation be worshiped. When you understand this, many other questions become smaller.” He went on to explain the concept of tawheed, the Oneness of God, and its many applications to our lives. I began to understand that this central belief of Islam was deep and all-encompassing.

“That is enough for today,” he said eventually. “Tomorrow we continue.”

“What do you think?” Haaris asked me when the lesson was over.

“I think I have a lot to learn.” That was the best I could offer.

Jum’ahThe next day was Friday. Once again I was relegated to housework. Once the early morning tasks were done, Ma Shushu and Haaris began hitching the donkeys to the carriage. The carriage was piled high with safflowers that the farm laborers had harvested yesterday.

“Are we going to town?” I asked.

“Haaris and I are going,” Ma Shushu said. “It’s market day, and it’s Jum’ah, the main day of prayer for Muslims. We will deliver the safflowers to my sister and a few others, then attend prayer.”

“What about me?”

Ma Shushu did not meet my eyes. “Your shoulder is not healed yet. The jostling of the carriage would not be good for you.”

As they departed, all I saw was the back of the wagon and a heap of flowers. I waved, but no one saw me. The whole thing was very strange, and I couldn’t feeling there was something I wasn’t being told.

They were hardly out of sight when Lee Ayi called me to the west side of the house. She nodded to the clothes on the lines.

“Help me take these clothes down and fold them,” she said, speaking quickly. “Then take the lines down.”

“Some of the clothes are still damp,” I remarked as I took down a pair of Haaris’s trousers.

“Doesn’t matter,” Lee Ayi replied. “We’ll put them back up later.”

This made no sense to me, but I did as ordered. Lee Ayi worked fast, rushing, which was not like her at all.

* * *

Come back next week for Part 6 – A Single Step

Reader comments and constructive criticism are important to me, so please comment!

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories on this website.

Wael Abdelgawad’s novels – including Pieces of a Dream, The Repeaters and Zaid Karim Private Investigator – are available in ebook and print form on his author page at Amazon.com.

Related:

The post Far Away [Part 5] – There Is Only Work appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Who counts?

A Maccabi Tel Aviv fan gives a Nazi salute at a match in Stuttgart, Germany

A Maccabi Tel Aviv fan gives a Nazi salute at a match in Stuttgart, Germany Last week the chief constable of West Midlands Police, Craig Guildford, retired after admitting presenting inaccurate information sourced from an artificial intelligence app, Microsoft CoPilot, in a report on the security situation that would ensue if the away fans of the Israeli football team, Maccabi Tel Aviv (MTA), were to be allowed to travel to Birmingham to see their team play Aston Villa. The information included mention of a fixture between MTA and West Ham, an east London side, which had never taken place. The mainstream media has been full of angry debate about who was a threat to whom in the event of the MTA fans coming; pro-Israel outlets and figures claim that the police, whom they claimed are under the sway of local ‘Islamists’, were underplaying the threat of local “Islamist thugs” to the Israeli fans while local MPs and Palestine supporters point to the club’s actual record of racist violence, both inside and outside Israel. In the event, the club withdrew the fans itself after a riot between their fans and another local team’s fans in Tel Aviv, but the latest revelations have prompted an orchestrated outrage from Zionists, securocrats and racists who claim that the MTA fans were blameless and that the opposition to them attending was motivated by antisemitism, or was antisemitic regardless of motive; this includes sections of the ‘official’ Left, notably including this sickening article by Gaby Hinsliff in the Guardian last Friday, who tells us that the affairs “stirs deep-seated fears” of being “obliged to retreat from mainstream spaces to spare everyone else the awkwardness of having to battle for their inclusion”.

How many times do we have to say that this is not about the right of Jews to walk any street they like, but about the ‘right’ of a group of foreign football supporters, most of whom have served in an army whose principal role is oppressing people, supporting violent settlers as they encroach on more and more native Palestinian land, and who have for the past two and a half years been slaughtering Palestinians in Gaza, to travel through the streets of Birmingham or indeed any other city in the UK where there is a large Muslim population? Let’s not forget that Russia has been excluded from international sport since its invasion of Ukraine in 2022, so there is no danger of its fans antagonising Polish or Ukrainian communities, and its war crimes, though still dreadful, do not approach genocide. Everyone who has been on a Palestine demonstration will know there are Jewish allies; you would not know who was Jewish and who was not unless they wore Haredi clothing and you do not know which of them supports Israel or not unless you ask or they tell. When it’s Jews who claim to feel threatened, of course, it’s another matter: when anti-genocide demonstrators wanted to demonstrate outside the BBC’s Broadcasting House on a Saturday, the day most people have off work, it was banned because there was a synagogue a few streets away.

The same people expecting Birmingham’s Muslims to tolerate this complain constantly about “fighting-age males” from Muslim countries being offered asylum, accusing them without any evidence of being a stealth invasion. We have been told that the real threat was to the Israeli fans and came from “Islamist thugs”, a phenomenon unseen in this country and who went unnamed but no doubt referred to the potential for demonstrations: actual peaceful demonstrations against Israel’s genocide of the Palestinians of Gaza and its ongoing ethnic cleansing of the West Bank are referred to as “hate marches” while the media refers to actual thugs who stop aid reaching Gaza as ‘demonstrators’ or ‘protesters’. There has been outrage that the panel which selected Craig Guildford included an imam; it would, surely, have included other faith leaders as well. It was meant to represent the community and Muslims are a major part of the community in Birmingham. Matthew Goodwin (who until recently was a senior fellow of the UAE-funded Legatum Institute, which now trades as Prosperity Institute) lectures us that “Islamists” are starting to have influence, not bothering to distinguish between Muslims and “Islamists”; it is natural, in a democracy, that sections of the community have influence over decisions that affect their lives.

Jews do not have a right to be cosseted if they choose to throw in their lot with violent football hooligans and a foreign power that is oppressively and murderously racist. They deserve to be held accountable. Over the past several years, we have been lectured endlessly that their feelings are all-important, that they must feel safe and they alone have the right to dictate what constitutes antisemitism (and it must be the right kind of Jews, i.e. not dissenting ones). David Baddiel wrote an entire book called “Jews Don’t Count”, castigating the Left for failing to acknowledge Jews’ feelings of oppression or to count them among the oppressed, regardless of their whiteness in an age when that matters more than anything else, their ample access to media and to power; people who question their status as an oppressed minority stand to lose out, as Diane Abbott did in the years before the 2024 election. Meanwhile, a drumbeat campaign goes on to drive Muslims out of public life, which has now culminated in a senior police officer losing his job for failing to treat Muslims with the contempt they believe we deserve. Yes, he made some stupid mistakes, but none of these are the reason he was forced out. We all remember the quote about Islamophobia “passing the dinner-table test”; we are now entering an age in which it is less risky to be racist than not.

Winter strikes with a vengeance

Palestine expert joins think tank funded by Britain's war industry

Julie Norman accepts post with Chatham House, which counts BAE Systems as a major donor.

Reform UK’s London mayor candidate condemned for burqa stop and search remarks

Laila Cunningham accused of endangering Muslims after saying it ‘has to be assumed’ people hiding their face for a criminal reason

Reform UK’s mayoral candidate for London has been accused of endangering Muslims after she said women wearing the burqa should be subject to stop and search.

Laila Cunningham, who was announced as Reform’s candidate for the 2028 mayoral elections last week, said no one should cover their face “in an open society”, adding: “It has to be assumed that if you’re hiding your face, you’re hiding it for a criminal reason.”

Continue reading...Babies die of hypothermia in Gaza as Israel blocks shelters

At least 100 children killed during “ceasefire” period.

Keeping The Faith After Loss: How To Save A Grieving Heart

Grief, an emotion, an exclusive state of being; a membership to which one never wants, but is nevertheless served. Thousands and thousands before me have lived through it, and many thousands more will come after me who will experience the aching pain of grief. I know for sure, each one of those lived experiences will be as unique as the leaves that drop from the trees at this time of year. As I finish yet another salah where I’m wiping away tears with my prayer garment, I feel an intense throbbing, deep inside my heart, a struggle that erupts out as tears. It seems to have no end.

It is a Sunday night, which means work tomorrow; the beginning of yet another week where I will carry my invisible yet ever-so-heavy grief around with me: finding that smile when greeting others, listening attentively, and communicating, because, as expressed in every language, life must go on. It’s now a little over a year since I lost my father. I have carried on in the best way I can, making sure I only cry behind closed doors. You see, the problem with that is, you are then always expected to carry on – so the invisible weight of grief becomes even heavier on the already constricted heart.

Understanding FateAt times, usually when I’m driving, I remind myself of the immense blessing of grieving for my father well into my forties. Allah  , Ar-Rahman, blessed me with a kind and loving father for over four decades – a gift many hundreds of people have not been privileged to have. I have seen close friends and family lose loved ones at much younger ages, and they have carried on beautifully. Why then does my heart hurt in this way? Am I an ungrateful soul? I’m not sure I know the answer to this. Can a grateful heart not feel pain? Isn’t pain also an emotion felt by the living, just as gratitude is? Just because I cry, does it mean I am not accepting of Allah’s

, Ar-Rahman, blessed me with a kind and loving father for over four decades – a gift many hundreds of people have not been privileged to have. I have seen close friends and family lose loved ones at much younger ages, and they have carried on beautifully. Why then does my heart hurt in this way? Am I an ungrateful soul? I’m not sure I know the answer to this. Can a grateful heart not feel pain? Isn’t pain also an emotion felt by the living, just as gratitude is? Just because I cry, does it mean I am not accepting of Allah’s  beautiful and perfect decree in my life?

beautiful and perfect decree in my life?

It is the human in us. The very thing that differentiates us from all of Allah’s  Creation is our ability to feel continuously. We love and are loved, but this does not mean that we don’t experience sorrow or are exempt from hurting others. We can be grateful, yet have endless tears. This is what makes us humans with hearts: a heart that is more than an organ, a heart that feels. This is what my year-long exclusive membership to the emotional field of grief has taught me. It is one of the many emotional states that will now be with me – until I myself leave this dunya. I can hide it, but I cannot avoid it. I may never find the right words to describe it, but every inch of my beating heart will feel it every single day.

Creation is our ability to feel continuously. We love and are loved, but this does not mean that we don’t experience sorrow or are exempt from hurting others. We can be grateful, yet have endless tears. This is what makes us humans with hearts: a heart that is more than an organ, a heart that feels. This is what my year-long exclusive membership to the emotional field of grief has taught me. It is one of the many emotional states that will now be with me – until I myself leave this dunya. I can hide it, but I cannot avoid it. I may never find the right words to describe it, but every inch of my beating heart will feel it every single day.

“Life has to go on, but how should a heart carrying the badge of grief carry on?” [PC: Duniah Almasri (unsplash)]

Life has to go on, but how should a heart carrying the badge of grief carry on? The Qur’an and the Seerah of Prophet Muhammad are my answer. You would think worship is easier for the one who loses someone dear, but no one talks about how you freeze with worship when grieving. How the heart has a yearning to connect with its Lord, but the mind remains still, lost and struggling to move. It is then that the years of holding the mus’haf close to the heart help revive it for worship. It is then, -knowing that the tears running down Muhammad’s (saw) face after losing his infant child, knowing he continued with his role as the last Prophet of Islam-, that this helps you take steps towards living life. We know about all the losses in his life, from before his birth; from the death of his father, to losing his mother, grandfather and then later his beloved wife and uncle. The seerah weighs heavily with death and grieving, but life, purpose and calling upon Allah

are my answer. You would think worship is easier for the one who loses someone dear, but no one talks about how you freeze with worship when grieving. How the heart has a yearning to connect with its Lord, but the mind remains still, lost and struggling to move. It is then that the years of holding the mus’haf close to the heart help revive it for worship. It is then, -knowing that the tears running down Muhammad’s (saw) face after losing his infant child, knowing he continued with his role as the last Prophet of Islam-, that this helps you take steps towards living life. We know about all the losses in his life, from before his birth; from the death of his father, to losing his mother, grandfather and then later his beloved wife and uncle. The seerah weighs heavily with death and grieving, but life, purpose and calling upon Allah  continue. It is then that you are reminded of what a real human experience of grief is, because in the example of the Prophet Muhammad

continue. It is then that you are reminded of what a real human experience of grief is, because in the example of the Prophet Muhammad  , we know is for us the ideal believer and human.

, we know is for us the ideal believer and human.

I don’t think anyone truly learns to live with grief. I think it can be soul-consuming; we either park it somewhere or find a way to carry it with us – but it is always there. At times, the intensity of missing someone, remembering their face, the pain they lived with, the sacrifices they made, all of this and more, can make us feel lost and detached from the every day of life. It is for these moments that having a daily relationship with the Qur’an brings focus back into our day, allowing us to understand how life can feel bearable.

For many years now, I have run a group of daily Qur’an recitation with other sisters. We recite ten verses a day and read the translation of the same ten verses. This has been running for over a decade now, but it was in my year of grief that the group was my anchor and I realised the true blessing of having a daily relationship with the Qur’an. For all the verses I had read and learnt about, they came as a soothing balm in my time of hurt. It allowed me not to be dismissive of feelings but rather gave meaning and purpose to the overwhelming fear that comes with mourning someone we love. It is a form of therapy, but with the Words of Allah  – His Speech – how can we not find comfort in it?

– His Speech – how can we not find comfort in it?

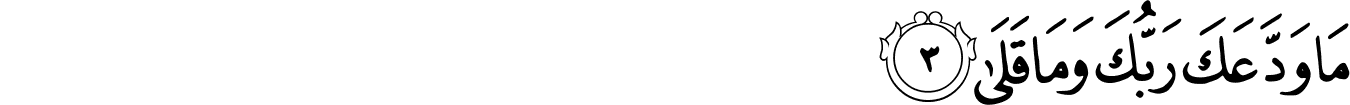

“Your Lord has not forsaken you” [ Surah Ad-Duha;93:3]

Dua’ – A Gift For The Deceased And For The LivingAfter a year-long journey of wiping away tears at night and walking with a forced smile during the day, I have taught myself to make dua’ for my father’s soul in a way I have not done so before. There is an enormous comfort in knowing that when we make dua’ for a departed soul, they benefit from it.

Abu Huraira

narrated that “The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, ‘Verily, Allah Almighty will raise the status of his righteous servant in paradise, and he will say, ‘O Lord, what is this?’ Allah will say, ‘This is (due to) your child seeking forgiveness for you.’” [Sunan Ibn Majah]

I cannot express in words how much relief this provides me. To know that my good actions can aid my father now allows me to continue; it allows me to want to do good, and it also helps this private experience to feel acceptable.

Allah  , The Most Wise, in His Wisdom permitted us, His servants, to know about this; to know that we can benefit those who have left the dunya. This knowledge that He has shared with us of the unseen is of great benefit for both the living and the dead.

, The Most Wise, in His Wisdom permitted us, His servants, to know about this; to know that we can benefit those who have left the dunya. This knowledge that He has shared with us of the unseen is of great benefit for both the living and the dead.

Abu Huraira

reported: The Messenger of Allah (saw) said: “When the human being dies, his deeds end except for three: ongoing charity, beneficial knowledge, or a righteous child who prays for him.” [Sahih Muslim]

It is by knowing this that a grieving believer can refresh and re-intend to carry out good. It is by knowing that I shall make every tear a means of dua’ for my father, but also live such a life that I do both: attempt at being a righteous child of my father’s, but also leave behind children who will also pray for me in this way. In order for this to happen, there is much work. And this is faith. This is what faith is like for us Muslims. It is not something confined to our prayer mats, but has to be present when we do everything else; and this includes when and how we grieve, too. It is only because of faith that I am able to navigate the waves of sorrow and understand its permanent residence in my life.

Related:

– Unheard, Unspoken: The Secret Side Of Grief

– Sharing Grief: A 10 Point Primer On Condolence

The post Keeping The Faith After Loss: How To Save A Grieving Heart appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

So much for a ‘final battle’ – once again the Iranian people’s peaceful and democratic demands have been silenced | Behrouz Boochani and Mehdi Jalali Tehrani

The protests were hijacked by Reza Pahlavi and notions of Persian supremacy, then brutally repressed by a violent regime

In late December, Iran experienced the beginnings of an uprising driven primarily by economic pressures, initially emerging among merchant bazaaris and subsequently spreading across broader segments of society. As events unfolded rapidly, calls for regime change became the focus of international attention. Consistent with its response to previous protest movements, the Iranian government once again opted for repression rather than engagement, violently suppressing demonstrations instead of allowing popular grievances to be articulated and addressed.

As visual evidence circulated depicting the accumulation of bodies at Kahrizak, it became increasingly evident that the primary instigator of the violence leading to these fatalities was the Islamic Republic itself, which has refused to tolerate civil unrest and has consistently responded to popular mobilisation with force.

Behrouz Boochani is a Kurdish writer. Mehdi Jalali Tehrani is an Iranian political commentator

Continue reading...Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism

Every dictatorship eventually collides with a problem it cannot solve by expanding prisons, perfecting surveillance, or laundering repression through emergency laws. That problem is conscience. Not the decorative conscience wheeled out in constitutional preambles or Friday sermons, but the dangerous, embodied kind: people who insist on calling crimes by their proper names, who refuse to perfume mass violence with the language of “security” or “complexity,” and who behave — almost scandalously — as if power were still accountable to principle.

Pakistan’s rulers understand this problem well. They have built an entire governing philosophy around neutralizing it.

In Pakistan today, Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan occupies precisely this intolerable space. He does not command mobs. He does not control institutions. He does not benefit from the romantic mythology reserved for martyrs or political prisoners. What he possesses instead is far more destabilizing to a regime addicted to fear and confusion: moral coherence. He behaves as if ethical clarity were not a public-relations liability to be managed but a responsibility to be exercised.

That posture — quiet, disciplined, unyielding — explains why he matters. It also explains why he is dangerous.

Moral Presence in an Age of Managed BrutalityAuthoritarian systems are, above all, management projects. Pakistan is no exception. It manages narratives, crises, alliances, dissent, and public memory with the meticulousness of a corporate risk department. What it cannot manage — what consistently escapes its spreadsheets and talking points — is moral presence.

Moral presence is disruptive because it refuses translation. It refuses to convert injustice into “context,” mass killing into “geopolitics,” or repression into “stability.” It insists that some acts are wrong regardless of who commits them, how eloquently they are justified, or how many uniforms are involved.

Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan’s politics operate in this register. His participation in the Gaza solidarity flotilla was not a publicity stunt or an exercise in symbolic humanitarianism. It was a direct refusal to outsource solidarity to press releases. At a moment when Muslim rulers perfected the art of condemning genocide in the passive voice — where Palestinians are always “dying” but never being killed — he chose presence over prose.

He crossed a line Pakistan’s generals, bureaucrats, and their Western patrons desperately prefer remain blurred: the line between rhetorical sympathy and embodied accountability.

That decision reverberated far beyond Gaza. It landed squarely in Islamabad and Rawalpindi, and in the quiet calculations of a regime that understands — perhaps better than its critics — how contagious moral consistency can be.

Two Consciences, Two CellsPakistan’s current moment is defined by a grim symmetry. Its two most morally resonant political figures now occupy opposite sides of a prison wall.

Imran Khan, jailed, censored, and methodically erased from public life, embodies the conscience of mass politics: the inconvenient truth that popular legitimacy cannot be indefinitely manufactured, managed, or extinguished. Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan, still free for now, embodies something the regime finds equally threatening: proof that ethical clarity does not require state power, mass rallies, or electoral machinery.

The regime grasps this distinction instinctively. Mass leaders can be isolated, demonized, or imprisoned. Moral leaders are harder to neutralize. They do not rely on crowds or cycles. Their authority travels horizontally, through example rather than command. It accumulates quietly, beneath the regime’s noise, until it becomes impossible to contain.

This is why Senator Mushtaq’s activism has sharpened rather than softened. Through the Pak-Palestine Forum and the Peoples Rights Movement, he has rejected the regime’s preferred compartmentalization — one in which Palestine is mourned abstractly while Pakistan is governed brutally, one in which foreign oppression is lamented while domestic repression is normalized.

He insists, instead, on linkage. That insistence is unforgivable.

The Crime of ConsistencyDictatorships do not fear hypocrisy. They depend on it. Hypocrisy is the lubricating oil for authoritarian rule. What they cannot tolerate is consistency.

“Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan’s politics operate in this register. His participation in the Gaza solidarity flotilla was not a publicity stunt or an exercise in symbolic humanitarianism. It was a direct refusal to outsource solidarity to press releases.” [PC: @SenatorMushtaq, US Social Media Company X]

To denounce Zionist apartheid rhetorically while collaborating with its regional enablers is acceptable. To mourn Palestinian corpses abroad while disappearing Pakistanis at home is standard operating procedure. To oppose domination — imperial, military, or ideological — without qualification is destabilizing. It deprives power of its favorite alibi: “context.”This is what unites the figures Pakistan’s current rulers find most intolerable.

Barrister Shahzad Akbar’s insistence that law should function as principle rather than weapon cost him safety and exile. Imaan Mazari’s defiance — amplified rather than tempered by her mother, Dr. Shireen Mazari — ruptures the convenient fiction that human rights must be suspended in imperfect governments. Dr. Mazari’s tenure as minister for human rights is dismissed not because it failed, but because acknowledging it would complicate the intellectual laziness of liberal gatekeepers.

Dr. Yasmin Rashid’s endurance, Ammar Ali Jan’s principled radicalism, and the courage of Baloch and Pashtun leaders resisting erasure under conditions bordering on colonial occupation all represent variations of the same threat: they refuse to turn politics into branding. They insist on substance where power prefers symbolism.

The regime’s response is uniform: criminalization, vilification, disappearance. Consistency is met with coercion because it cannot be bargained with.

The Unnamed Majority and the Regime’s Real FearTo focus only on prominent figures, however, is to miss how resistance actually survives.

Dictatorships are not undone by heroes. They are undone by accumulation — by the steady aggregation of small refusals. A taxi driver who speaks honestly despite surveillance. A teacher who refuses to recite official lies. A lawyer who takes a case she knows she will lose. A journalist who documents one more testimony before the knock comes.

These people will never be celebrated. That is precisely why they terrify power.

Authoritarianism survives by convincing people that their courage is singular. Fear isolates. It interrupts accumulation. It persuades individuals that resistance is futile when, in fact, it is shared.

Pakistan’s rulers invest obsessively in fear because they understand this arithmetic.

Palestine as a Moral X-RayLinking Palestine to Pakistan’s internal crisis is not a rhetorical excess. It is an analytical necessity.

Palestine functions as a moral X-ray of the contemporary world order. It reveals how easily states abandon principle when convenience beckons. It exposes the vocabulary through which mass murder is sanitized — “security,” “self-defense,” “rules-based order” — how those same vocabularies migrate seamlessly into domestic repression.

Zionism, as practiced by the Israeli state, is not an aberration. It is a concentrated expression of a global logic that treats some lives as disposable and others as strategically valuable. The same logic that justifies the annihilation of Gaza authorizes the pacification of dissent in Pakistan.

When Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan speaks against apartheid-genocidal Israel, he is not performing internationalism. He is diagnosing a system. That diagnosis unnerves Pakistan’s rulers because it collapses the distance they rely on. It reveals that the victims of empire recognize one another — even when their oppressors coordinate discreetly.

The Regime’s DilemmaPakistan’s rulers depend on fragmentation — between causes, movements, and moral vocabularies. They prefer activists who choose single issues and avoid dangerous connections. They are deeply threatened by figures who connect dots.

Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan does exactly that. He refuses to choose between Palestine and Pakistan, between anti-Zionism and anti-dictatorship, between faith-based ethics and universal human dignity. He insists these struggles are not adjacent but inseparable.

That insistence is his protection and his peril.

For now, he remains outside prison. History suggests this is rarely permanent.

The Final AccountingA reckoning will come. Prisons will open. Files will be read. Silence will be reclassified as collaboration.

When that day arrives, many will rediscover their principles retroactively. Some will plead ignorance. Others will invoke “complexity.” A few will insist they were merely pragmatic.

Very few will be able to say they spoke plainly when plain speech carried a cost.

Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan will be among them.

So will the thousands whose names will never appear in essays like this.

Dictatorships do not fall because they are exposed. They fall because they are exhausted by the relentless refusal of ordinary people to surrender their moral vocabulary.

That refusal is Pakistan’s most valuable resource.

And it remains — despite everything — uncaptured.

[Disclaimer: this article reflects the views of the author, and not necessarily those of MuslimMatters; a non-profit organization that welcomes editorials with diverse political perspectives.]

Related:

– Allies In War, Enemies In Peace: The Unraveling Of Pakistan–Taliban Relations

The post Op-Ed: From Pakistan To Gaza – Why Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan Terrifies Power And Zionism appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Livestream: US-Led aggression from Gaza to Venezuela

We talk to Justin Podur about imperialism and collaborators and US “victories.”. Palestine’s resistance salutes Venezuela. Ali Abunimah wins a court victory in Switzerland and more.

New wall threatens thousands of Palestinian families

Has New York really ended Betar's campaign of Zionist terror?

Pro-Israel extremists perpetrated violence, intimidation and harassment targeting Palestinian, Arab, Muslim activists, state finds.

The Sandwich Carers: Navigating The Islamic Obligation Of Eldercare

The sandwich generation, or ‘sandwich carers’, refers to adult individuals who provide unpaid care to ageing parents or older relatives while simultaneously raising their dependent children. In the UK, around 2% of the population1 provides “sandwich care,” balancing responsibilities for both children under 16 and older adults in need of support. Whereas in the US, the percentage is much higher, with 23% of adults “sandwiched between their children and an ageing parent.”2

This study proved that – unsurprisingly – sandwich generation carers are at a greater risk of mental health struggles and need support.

Equity In EldercareIn my youthful naivete, I strongly believed that when it came to looking after one’s ageing parents, it had to be distributed equally according to the number of children. By my logic, if an elderly couple had four children, then all four of them had to take turns to look after their parents. Only children have the responsibility of caring for both ageing parents with no siblings to lean on, except for a loving and supportive spouse, if they have one.

Many decades later, I have come to realize that no matter how many children there are in a family, except in rare circumstances, the bulk of eldercare usually falls on one adult child and his/her spouse and children. One of my friends, a Malaysian cardiologist who encounters many ageing elders, echoes seeing the same thing in her clinical practice across both Muslim and non-Muslim families.

The rise of individualism in today’s world is probably a driving force in elder neglect. When families lived closer together, the norm was for all children to help in the care of their elders. With the rise in economic migration and diaspora Muslim communities, the elders who did not move with their children are often left behind in their old age.

Cultural Expectations vs Islamic ObligationsThere seem to be many cultural “myths” when it comes to caring for elders. In Malaysia, where I live, the responsibility for eldercare often lies with adult daughters, even if families have sons. This may be due to the strongly matriarchal society and women often being the main income earners. In other parts of the world, the emphasis is on adult sons looking after their parents, even if they also have daughters. Desis have an expectation of the eldest son caring for his parents, when the actual work gets shifted onto his wife.

The reality is this: Islamically, eldercare responsibility lies on all adult children, regardless of gender. Caring for one’s parents is a fardul ‘ain (individual responsibility), and not a fardul kifayah (communal responsibility). One child caring for an ageing parent does not lift the responsibility from other children.

An Unfortunate Bias

“The reality is this: Islamically, eldercare responsibility lies on all adult children, regardless of gender.” [PC: Raymond Yeung (unsplash)]

Often, the hidden subtext of the adult son looking after his parents is this: while he goes to work and earns an income to support his family, it’s actually his wife who is expected to look after his parents. She’s the one already looking after their children, after all, so the cultural expectation is for her to extend her caregiving duties to her in-laws. Why not? She’s already at home, anyway, right?Caring for her in-laws is not her Islamic obligation – her obligation is to care for her husband, children, and her parents! Undoubtedly, she will be rewarded for caring for her in-laws, but once again, that is not her obligation. A daughter-in-law caring for her husband’s parents is a recommended act which is not lost on Allah  .

.

However, it’s important to realize a burnt-out daughter-in-law will be less likely to fulfil her actual obligations: her husband and children. May Allah  guide and have mercy on all of our families, and help us all do better.

guide and have mercy on all of our families, and help us all do better.

When it comes to equitable eldercare, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for families who are spread throughout the globe. Even with all adult children in the same city, eldercare is probably not distributed equitably either. Someone will have to sacrifice something for an unknown period of time.

In the best case scenario, all adult siblings step up in their best ways possible, put their differences aside, and work as a team to care for their ageing parents. Sadly, this is not always the case. When eldercare is left to only one adult child and his/her household, it can be so frustrating to ask for help, only to have minimal response from other siblings.

What helps is always turning to Allah  and making choices that align with His Pleasure. If you are bearing the load of eldercare, please know that this is a sign of Allah’s Love and honouring of you, through service to your elderly parents. Their dua’s for you will bring about tremendous goodness to you – even if it may not be immediately apparent.

and making choices that align with His Pleasure. If you are bearing the load of eldercare, please know that this is a sign of Allah’s Love and honouring of you, through service to your elderly parents. Their dua’s for you will bring about tremendous goodness to you – even if it may not be immediately apparent.

If you are the main carer for both elders and young children, here are some tips that may help:

1) Build a strong support network: Nobody can look after elders or children on their own without burning out, let alone when looking after both age groups! Please don’t wait until you are on the brink of a mental breakdown, but rather proactively have a conversation with family and/or loved ones, and discuss how everyone can help support you in caring for the elders under your care.

2) Build in breaks: Try your best to build in regular daily, weekly, monthly and yearly ‘pressure release valves’ – for lack of a better term. When family comes to visit and spends quality time with your ageing elder, use that opportunity to rest and recharge.

3) Elder vacations: Before elders struggle with more severe health issues, arrange for them to go for a holiday in another adult child’s household. Even if they might be reluctant to leave their comfort zone, this break will give a much-needed respite for the main household of carers.

4) Acceptance: Sadly, as health issues often worsen in old age, there will come a time when ageing parents will no longer be able to travel. This is the time for them to be visited and cared for, especially by adult children who live far away or are absent for other reasons.

ConclusionImam Ahmad narrated that Usamah bin Sharik (may Allah be pleased with him) said, “I was with the Prophet Muhammad (Alla when the Bedouins came to him and said, ‘O Messenger of Allah, should we seek medicine?’ He said, ‘Yes, O slaves of Allah, seek medicine, for Allah has not created a disease except that He has created its cure, except for one illness.’ They said, ‘And what is that?’ He said, ‘old age.’” [Ahmad, Tirmidhi, Abu Dawud]

Marriage is a lifelong commitment that not only includes the care and raising of children, but also the care and burying of elders. When families were closer together and Islamic values were more prevalent, discussions around eldercare weren’t even necessary among siblings. Elders were cherished and cared for by their adult children and grandchildren until the end of their long and blessed lives.

Now, there needs to be a revival of more intentional conversations around eldercare, especially with the rise of individualism and the cultural bias that expects only eldest/youngest sons to do the heavy lifting. Every single adult child has a role to play, even if it’s inconvenient. The door of service to our elders is a golden opportunity that only lasts for as long as they are with us in this dunya. Once they pass away, that door closes, never to be opened again.

Related:

– Avoid Financial Elder Abuse Through Islamic Principles

1 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S00333506240049792 https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/04/08/more-than-half-of-americans-in-their-40s-are-sandwiched-between-an-aging-parent-and-their-own-children/The post The Sandwich Carers: Navigating The Islamic Obligation Of Eldercare appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.