A lonely convert quits cigarettes cold turkey in Ramadan, and the brutal withdrawal becomes the fire that burns her into a new life.

Note: This is part two of a two-part story. Read Part 1

* * *

Cold Turkey

Alone in her apartment, the words “cold turkey” tolled in Mar’s head like the call of a body collector during the Black Plague: “Bring out your dead!” The phrase recalled the many attempts she’d made to quit smoking, all of which had failed: the hypnotherapist with the soft voice, the rubber band snapping against her wrist until it left welts, the week she had eaten nothing but grapefruit and smoked twice as much from hunger. The last attempt had been seven years ago. After that she’d given up and resigned herself to a life of addiction, and an early death.

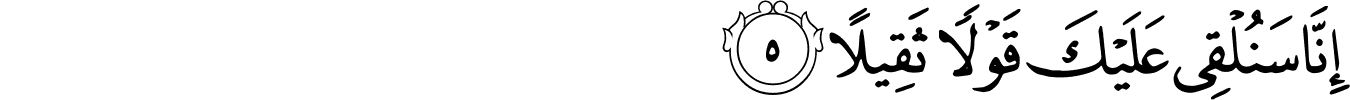

It didn’t matter. She must try again, and she must succeed this time, not for herself but for Allah. For her life, her soul, her hereafter – there was an Arabic word for that, but she didn’t remember. It didn’t matter if quitting cold turkey killed her – and she believed it might. She had to rid herself of the baby god, once and for all.

The thought filled her with such terror that she sat on the bed so she wouldn’t fall.

But beneath the terror there was something else – not relief, not yet, but the faintest sense of a pale ray of sunshine breaking through a wall of iron-gray clouds. For the first time in thirty years, she had hope.

Destroying the Baby Gods

Her resolve was fully formed, like a tornado that had sprung up on a summer day and was ready to tear through everything in its path. The apartment was dim, late afternoon light struggling to slip through the gaps in the smoke-stained curtains. Mar threw the curtains wide open, then went to her closet, where she dug the pack of cigarettes out of the pocket of the old winter coat. There was an entire carton under her bed, and she pulled that out as well.

It was not enough to throw them away. She could always get them out of the trash. Even if she took them to the dumpster downstairs, she wouldn’t put it past herself to go down later and climb in among the wet garbage to retrieve the cancer sticks.

She took all the cigarettes to the bathroom and kneeled over the toilet. Shaping her hands into claws, she began to destroy the beautiful, evil little sticks.

She tore the cigs apart over the toilet, letting the loose tobacco and shredded papers fall in. She flushed the toilet, then tore more cigarettes apart. Flushed. More destruction. Flushed. It was a violent, hateful, triumphant act. Yet she also felt grief. Tears spilled from her chin into the swirling water. These filthy little sticks had been her only friends for so long. They’d been there for her when everyone else had cut her off. And now she was destroying them. The sadness was almost too much to bear.

She held the lighter for a long moment. It was not a cheap disposable piece of junk, but a chrome and 14K gold luxury lighter by Dupont. Refillable. Her one luxury, purchased on credit and paid off over a three month span. It had been her gift to herself when she was promoted to supervisor. She fell to her knees and elbows on the bathroom floor, caressing the lighter with her thumbs. She loved its smooth lines and golden gleam. She brought it to her lips and kissed it sweetly, then rubbed it on her cheeks. Baby gods, she thought. Rising, she unscrewed the lighter and emptied the fuel into the toilet. Then she dropped the lighter on the floor and stomped on it viciously, again and again, until the downstairs neighbor shouted and banged on the ceiling. She picked up the mangled lighter, took the elevator down to the street, and threw it into the dumpster.

She was done. No more smoking, now and forever. No more baby god, no monkey on her back.

She went upstairs and prayed ‘Asr, and asked Allah to strengthen her for what she knew was coming. The dread was deep in her belly, as if she’d swallowed a cannonball with a short, sparking fuse, and the explosion was imminent.

If there was such a thing as damnation on earth, she was about to enter it.

Withdrawal

The first night she did not sleep at all.

Her skin crawled as if ants moved beneath it. Every position in the bed became unbearable after seconds. She threw the blanket off, dragged it back on, kicked the pillow to the floor, retrieved it again.

Her heart raced without reason. By morning her head throbbed so violently she had to crawl to the bathroom to vomit. Did that break her fast? She did not know, but she would continue fasting. It had been 18 hours since she’d smoked.

She prayed Dhuhr sitting on the edge of the bed, her back against the wall, because standing made the room tilt. The hours stretched mercilessly. Every minute seemed interminable. She was absolutely sure that insects were crawling beneath her skin. She scratched feverishly until her arms and legs bled.

She tried to read the Quran and could not hold a single line in her mind. The words blurred. She kissed the book and set it aside.

The cravings did not come as desire but commands:

Smoke now. Go down to the corner store and buy one pack. No one will know. Going cold turkey is insane, you might die. Taper off instead. You could be smoking ten minutes from now. Don’t you want that sweet relief? Who cares about the Dupont lighter, screw the lighter. Buy a cheap Bic instead. Okay, then just one cig. One only, what’s the harm? You’re sick, you have an excuse to break your fast.

And on and on.

Thirty hours without a cig. She lay in bed, curled on her side, and pressed her forehead into the headboard until a towering wave of nausea passed. Her head was splitting down the middle, as if an axe were buried in her skull.

Saturday she did not open the curtains.

Sunday she left the apartment only once, for a frozen burrito and a bottle of apple juice for iftar. The walk to the corner store felt like crossing a desert.

“The usual?” the store clerk asked. Young man with curly blond hair. Surfer type. Healthy. Definitely not a smoker, nor a Muslim. So not one of her people on either count.

“What do you mean?” Her voice came out hoarse.

The cashier studied her with open concern. She hadn’t brushed her hair, and might even have dried vomit on one cheek.

“Your usual brand,” the clerk elaborated. “Filtered, extra long. Two packs?”

The question pierced her. She almost stumbled backward. But instead she put the money on the counter, her hand shaking violently.

“No cigs,” she said. “Just the food.”

Understanding dawned in the clerk’s eyes. He gave her a supportive nod and returned the change.

Trial By Fire

She called in sick to work. “I have the flu,” she told her supervisor’s voicemail, her voice raw and unrecognizable. She took the entire week off.

The nausea, muscle cramps, and dizziness were constant. Pain seeped into her bone marrow. She would have gone to the hospital if she could have gotten out of bed. Yet she continued her Ramadan fast. She’d always considered herself a weak person, someone with no grit, no reservoir of willpower. Yet through it all she continued fasting, like a dog gripping a bone in its jaws, not letting anyone take it away.

Her phone lay beside her like a dead thing. No one called, neither from work nor from the masjid. On Wednesday she was too sick to attend the converts meeting. She felt terrible about it, because she’d promised that charming couple, Layth and Khadijah, that she would be there. Mar had not taken Khadijah’s phone number – she wasn’t brave enough to ask – and had no way to contact them. They would think she’d flaked on them. They were the only people who’d shown her any kind of friendship, and she’d ruined it already.

When she had the energy she read the Quran. When she didn’t, she listened to it on her phone, and it soothed her like water poured over a parched desert plant. The sound of the recitation, even when she did not understand, was honey to her soul.

Thursday she had a massive fit of nausea during the daytime hours, throwing up again and again, until all that came up from her gut was thin streams of liquid.

She got Imam Ayman’s number from the masjid website and called.

“As-salamu alaykum. This is Mar.”

“Sister Maria?” His voice was uncertain. “You sound different.”

She suppressed a surge of irritation that he still didn’t know her name. “It’s Mar, not Maria. Does vomiting break the fast?”

“If it’s unintentional, no. But if you make yourself vomit intentionally, the fast is broken and you must make up the day.”

“Why would I make myself vomit on purpose? I was sick, that’s all.”

“Yes, sorry. Sister Maria – I mean Mar. Are you okay?”

“Thanks brother Imam.” She hung up the phone.

Personal Problems

An hour later sister Juana called. “Ayman was worried about you. Is there anything I can do for you?”

Mar hesitated. “Personal problems,” she said finally, and hung up the phone.

She woke from a nap and noticed a slip of paper under her door. “I knocked but no one answered. Hope you are alright. Enjoy the halal food. – Juana.”

She opened the door and found a covered dish filled with chicken taquitos. She didn’t know how Juana had gotten her address, until she remembered filling out a contact form at a masjid fundraiser her second week there. She put the dish in the fridge. She felt something. Not gratitude. More like a spark of hope that someone actually cared. The married couple, and now Juana. It was something to hold on to, for now.

Passing of the Storm

That relentless vomiting fit was rock bottom. After that the physical agony began to recede. The tremors stopped, and the headaches faded. Her lungs ached, however, and she began to cough heavily. She coughed up gob after gob of dark mucus. She was terrified that her lungs might be coming apart, she might be coughing up pieces of the tender tissue.

The cravings were not gone, but they came now like dark whispers rather than forceful commands.

She felt utterly emptied out. Weak, yes, but mostly just limp and half-broken, as if she had run a marathon, and at the finishing line had been beaten up by a biker gang. It had been nine days since she’d smoked a cigarette. She had never done this before in her adult life. Had never believed she could. If miracles happened to ordinary people, then it was a miracle.

Her appetite returned. She ate some of Juana’s taquitos. They were good. She almost imagined she could taste them, but that was wishful thinking. Her taste buds were dead.

On Monday she was well enough to go to work. The coughing persisted, so she wore a mask. At mid-morning, after catching up on emails, she summoned Sarah Kim to her office.

The young woman stood in front of her, guarded.

Mar rose from her chair, approached the young woman. “I need you to be honest,” she said. “Do I still stink?”

Sarah blinked, caught off guard. She hesitated, then stepped closer and inhaled tentatively. Her nose wrinkled immediately.

“Yes,” she said, almost apologetically. “It’s… in your clothes. And your hair too, I think.”

Mar nodded once, her lips pursed. “Thank you for your honesty.”

The Purge

The discount clothing store was harshly lit and nearly empty. She bought everything in practical colors and sizes. Skirts long enough for salat, loose blouses with long sleeves, underwear, socks. A coat and scarf. A new pair of shoes.

At home she showered and put on the new clothes immediately, the fabric still stiff. Then she began throwing everything out. Every article of clothing she owned went into trash bags. She emptied the closet and dresser, and dumped the dirty clothes out of the laundry hamper.

Then she turned her attention to the linens. Sheets and pillowcases, towels, and even the shower curtain went into trash bags. Maghreb arrived. She broke her fast on a bean burrito and apple juice, prayed Maghreb and went back to work. When she was done there were six full trash bags on the floor.

She carried them down to the dumpster in three trips, her arms shaking from the weight, and threw them in without looking back.

She wasn’t done. In the bathroom she took the trimmer she used for her legs, and shaved all the hair off her head. It fell in clumps into the sink, looking like a mess of half-eaten straw. She stood there looking in the mirror at her bony skull, which she had never seen. She looked like a walking skeleton. She shrugged and said, “La ilaha il-Allah.” Everyone else could judge her, but only Allah’s judgment mattered.

She showered again, then dressed in the new clothes, wrapping the new scarf around her head with clumsy fingers.

Then the biggest jobs of all: She dragged the mattress onto its side and pulled it down the steps. Her lungs heaved, and she broke into repeated coughing fits, but she got it downstairs on her own, and left it beside the dumpster.

Then she mopped the floors on her hands and knees, rinsing the bucket again and again as the water turned the color of weak tea. When she was done with that, she turned her attention to the walls. She worked all night, stopping periodically to drink water or apple juice.

When her phone sounded the adhaan for Fajr, she prayed on the bare floor, then slept on the floor, curled up against the cold.

The Answer

She arrived at work with her eyes rimmed in red, her body moving on its last fumes of energy. She called Sarah Kim into her office again.

“Again,” Mar said. “Please.”

The young Korean-American woman rolled her eyes, half-smiling this time. She stepped close, leaned in, inhaled.

Her expression changed.

She inhaled again, more deeply, as if testing her own conclusion.

“No,” she said, with unmistakable surprise in her voice. “You don’t stink.”

For a moment Mar did not understand the words.

The workspace outside her door hummed with the usual sounds – phones ringing, keyboards clicking, someone laughing too loudly.

“No?” she repeated.

Sarah shook her head. “No. You smell like soap.”

Mar sat down in the chair as if her legs had given out. She pressed her palms against her eyes. When she removed them, Sarah Kim was gone.

Converts Night

It was Wednesday, exactly two weeks into Ramadan. She chose vanilla cupcakes because vanilla was the cleanest smell and flavor, even if she herself could neither smell nor taste. The loss of her sense of taste had happened so gradually that she only knew she’d been affected by the way other people reacted to food and scents. A dinner companion might say, “These rolls are incredible!” Yet to Mar they were flavorless. Her workers would complain on Mondays that the office stank of lemon cleaner, yet she didn’t smell it.

She used no spices or special flavorings. Just flour, sugar, eggs, butter, and a careful hand with the mixer. She washed her hands twice before starting, terrified that some invisible residue of her old life would seep into the food.

She arrived at the masjid early and set the cupcakes on the counter. No one would know they were hers.

She was the first at her table. When others arrived, no one sat near her. They filled the other tables first, then finally a few came to hers when there was nowhere else to sit, even then keeping their distance.

She knew for a fact that she didn’t smell bad. It was as if they were so used to her stinking, they took it as a given now.

Juana was there, but she was busy in the kitchen. Every time someone walked through the door Mar turned her head, hoping it would be Khadijah and Layth. But they did not appear. So she folded her hands in her lap and kept her eyes on sister Ranya at the front of the room as she spoke about Ramadan being the month of mercy.

Where is the mercy for me? she wondered.

When the lecture was done and the food was served, the people ate all her cupcakes. When she collected the empty tray, a short African-American sister named Swiyyah saw her and froze.

“You made those cupcakes?” Swiyyah said. She looked horrified, as if she had eaten poison.

Mar nodded. “Were they good?”

Swiyyah swallowed. “Did you – did you wash your hands first?”

Mar stared at the woman, unable to believe what she was hearing. Is that what people thought? That she was just dirty?

Mar wanted to say… She didn’t even know. What she actually said was, “Allah forgive you, sister Swiyyah. And I forgive you too.”

Swiyyah, looking like a rabbit in the headlights of an oncoming car, scurried away.

Renounce What People Possess

Imam Ayman was talking to a brother in the hallway. She waited until they finished, then approached him. “Brother Imam. Can I ask you something?”

He smiled, giving her his full attention. “Of course, sister Mar.”

She flashed a weak smile. “What can I do…” She paused, trying to keep her voice steady. “To make the sisters like me?”

He nodded slowly. “I have seen that you stay apart.”

“No,” she said softly. “I don’t choose that.”

“Oh. Something happened?”

Mar looked at the ground. There was no way she could tell him that the sisters avoided her because she used to stink of cigarette smoke. No way she could say those words. So she said nothing.

“There is a hadith,” the Imam said, “in Riyadh As-Saliheen. The same question you are asking. A man came to the Prophet ﷺ and said, “O Messenger of Allah, guide me to such an action which, if I do it, Allah will love me and the people will also love me.” He said, “Renounce the world, and Allah will love you; and renounce what people possess, and the people will love you.”

Mar frowned. “I’m supposed to live like a monk? And what does that mean, renounce what people possess? I have no claim on anyone’s property.”

“Renounce the world means give up our hunger for the things of this world. Of course we live in this dunya. We can own homes, have spouses, own cars. But those things can never be more important than Allah.”

“Or they become baby gods.”

Imam Ayman snapped his fingers. “Someone was listening!”

“And the second part? Renounce what people possess?”

“It means have no envy or competitive desire for what other people have.”

“I don’t have that.”

“We could extend it,” the Imam said gently, “to mean have no desire for their approval. Do not seek or chase their love. Chasing approval is like chasing your own shadow, you will never catch it. Release your desire for that. Do that, and they will love you.”

Mar shrugged helplessly. “It’s like a Zen riddle. When the student is ready, the master appears.”

Ayman chuckled. “I don’t know that one, but it’s good. But let’s make it concrete.” He rubbed his chin with one finger. “When the Prophet, sal-Allahu alayhi wa sallam, first arrived in Madinah, the people asked him what they should do. He said, ‘Spread the salam and feed the people.’ That’s the formula. Serve Allah and serve the creation for His sake. Be one of the people behind the scenes, working, asking for nothing.” He nodded to Juana, who was rounding up a few young brothers to put away the folding tables. “Like that.”

“She doesn’t get paid for that?”

Ayman smiled. “I wish. But no. The thing is, when you work only for the pleasure of Allah, and not for the people, then no matter what happens, you will have Allah’s reward, and that’s all that matters.”

“So I shouldn’t worry if everyone hates me?”

“Astaghfirullah, they don’t hate you. But listen. Right now your heart is being trained. Let it attach to the One who does not turn away.”

New Strength

The second half of Ramadan truly came alive for her, just as she herself came alive. She could feel the life flowing back into her veins day by day. The yellow tint faded from her skin, which regained a natural pink hue. The transformation was shocking. New strength flowed into her limbs. Energy coursed through her like water over a waterfall.

She began baking cookies and leaving them in the break room at work. At first only a few people sampled them, but soon the dish was empty by lunch time. One by one she called her workers into her office and apologized for mistreating them in the past. She promoted Sarah Kim to floor manager, and recognized the three most productive workers with generous grocery store gift certificates. One morning as she walked into the building, a few of her workers held the elevator for her. She rode up grinning.

On the BART or bus she listened to the short surahs of the Quran, mouthing the words, memorizing them. At work, she prayed Dhuhr in the break room. She heard some muted laughter the first day, but not after that.

She found herself experiencing hunger for the first time in Ramadan, and took it as a good sign, as if her body was saying, “Forget the cancer sticks, give me food!” She was sometimes low on energy at work, but resisted the temptation to spread a blanket on the floor of her office and nap. After all the times she’d shouted at her workers for being lazy, she didn’t imagine that would go over well.

She was starting to realize that her abusive behavior of the past had been a combination of spiritual emptiness, personal bitterness, and nicotine-fueled anxiety. She wasn’t entirely free of all that yet. She knew that. It was something to work on in Ramadan, inshaAllah.

At home she passed the time praying, reciting dhikr on her sabha, or reading sci-fi novels – an old hobby that she had revived. It astounded her how much free time she had all of a sudden. Not that she’d been a huge eater, but preparing food, eating, and cleaning up all took time, and suddenly that time had opened up for her.

When cooking or baking, she listened to Yasir Qadhi’s lecture series on the life of the Prophet. She bought a second set of clothing, and new sheets and towels. She could not afford a new mattress, but she bought an inflatable camping mattress, leaning it up against the wall during the day. Fair to say, she had renounced the world, for the most part.

Her new bedtime ritual – rather than leaning on one elbow, falling asleep as she inhaled poison – was dua. She sat cross legged in the bed, hands raised, and recited long, improvised duas, asking Allah to guide her, purify her, and keep her on the path. She prayed for the Ummah, and for the people of Palestine. She even prayed for the sisters at the masjid, not asking for them to like her, but asking Allah to grant them a beautiful Ramadan.

Coughing and Cravings

She still had painful coughing fits in which she hacked up brown and black flakes. Sometimes she ended up doubled over and dizzy. She had one such fit at work, and fell down on the floor, in front of everyone. Sarah Kim wanted to call an ambulance, but Mar waved her off. She heard one of her workers whisper, “Looks like the wicked witch is dead.” Apparently the bad old days were not completely forgotten. She couldn’t blame them.

The coughing scared her. Maybe she’d stopped smoking too late. Maybe she had lung cancer or emphysema. She would see a doctor after Ramadan, inshaAllah.

The nicotine cravings still came, especially at night, and with unexpected strength, descending upon her like fugue states. Completely unaware, she’d find her hand reaching for her right front pocket, where she kept the lighter. She would intensely anticipate the first draw of smoke, and would realize with a flare of disappointment that it wasn’t coming.

When this happened, she reminded herself of all that went along with the smoking: standing in dirty alleys in the rain; burning her bed and body; having to drink alcohol to reverse the effects of nicotine so she could sleep; waking up every morning feeling like her mouth was a garbage dump; being unable to breathe or climb a flight of steps; everything she owned stinking of smoke; the failed relationships, the anxiety and nasty temper, and spending ten percent of her income on something that was killing her. All of that was the true face of smoking. There was no glamor, pleasure or peace. It was staccato suicide.

A Time of Service

She went to the masjid on Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays. She got to know the Ramadan routine there, and found ways to serve. She came early and wiped the tables. Before iftar she set out dates and water. She refilled the water cooler, and took out the trash after Ishaa. She stacked the chairs, and learned how to use the chair dolly to move the stacks into the corner. She learned how to put the round tables away by turning them on their sides, folding in the legs and rolling them into the corner. She avoided tasks that required interacting with people, like serving food.

At the convert meetings, the sisters still shut her out. She always brought baked treats, but if the sisters knew which dish she had brought, they avoided it. That hurt.

She often found herself working in close quarters with Juana, and the two of them chatted about Ramadan and their lives. “Jazaki Allah khayr,” Juana would say when they were done. Mar didn’t know the Arabic response, and would reply, “Thanks. You too.”

No one else thanked her for her work. Maybe they thought she was a paid cleaning lady. It didn’t matter, it didn’t bother her. Turn to the One who does not turn away, the Imam had said.

Okay, yes, sometimes it still bothered her. One night she was washing dishes. The meeting had just wrapped up. Juana was not there, and while a few of the brothers were stacking chairs and folding tables, Mar was the only woman tending to cleanup. An Arab sister whose name Mar did not know entered the kitchen and dumped a stack of dirty dishes in the sink, not even acknowledging Mar.

Mar’s nostrils flared. She didn’t need this BS. She smacked the faucet handle to turn off the flow, yanked off the yellow dishwashing gloves and threw them in the sink, then snatched up her things and walked out into the darkness. The bus was approaching. Perfect timing. She waved it down, then hopped in, paying with her pass card. The bus was empty. She sat in the front seat, shaking her head at the rudeness and arrogance of some people. Why was she wasting her time? She could be at home relaxing, not serving a bunch of ingrates.

Renounce the world, she thought. Renounce what people possess. And the Imam’s words: “Be one of the people behind the scenes, asking for nothing. Do it for Allah.”

She pulled the cord to stop the bus, got off at the next stop, then walked four blocks back to the masjid. One of the young brothers had taken over the job of washing the dishes. “I got it,” she told him, and he seemed happy enough to be let off.

She had to wait a long time for the next bus.

She prayed taraweeh at home, reciting the short surahs she had learned. She had memorized the praises for the bowing and prostration. Only in the seated posture did she still have to read the praises from a paper. When standing, her legs were strong, and at times she lost herself in the salat, losing her sense of time.

Widening Circles

Mar was still coughing up colored mucus, and it worried her, but she had noticed that after each coughing fit her breathing was more free. She hoped that her lungs were ridding themselves of thirty years of contamination. She still planned to see a doctor, but she was afraid.

Ramadan ended, and Mar was sad to see it go, for Allah had brought her back to life through it. Next Ramadan she would enter clean inshaAllah, without the anchor of addiction pulling her down. That would be glorious.

At the Eid prayer, held at the Cow Palace, there were a thousand women in attendance. She’d never seen so many Muslims. Random Arab and Pakistani sisters she had never met hugged her, while – ironically – the ones she knew from the converts meeting avoided her. It almost made her laugh. SubhanAllah. It was as if the scope of her faith was steadily widening, from the Wednesday converts meeting to the entire community, the global Ummah, and – most importantly – her relationship with Allah. As the circles widened, the old problems and pettiness lost their power to burn, becoming bee stings rather than bear bites. She had, she realized, renounced what the people possessed.

Toward the end of the Eid gathering, Mar stood outside under the shelter of an awning – it was drizzling slightly – watching the families stream out into the parking lot and head off to their cars. She loved seeing the huge variety of cultural outfits. She knew she was boring and plain by comparison. Just a generic white woman.

Someone seized her from behind, and she let out a yelp.

“You look,” the woman behind her said, “like Mama locked the door and left you out in the cold.”

Mar turned, and gave Khadijah a hug. They chatted happily for a few minutes until Layth came along, wearing jeans, a long Arab shirt and a white and gold kufi.

Khadijah invited Mar to their home for lunch.

“You don’t have to,” Mar said. “I’m okay by myself.”

“That dog won’t hunt,” Khadijah insisted.

Layth and Khadijah had an apartment up in Bernal Heights. Mar and Khadijah talked while Layth cooked. When he set the food out, Mar was astounded. There was grilled carp, slow-cooked lamb and rice, and stuffed grape leaves.

When Layth asked how the food was, she lied and said it was delicious. In reality, it had very little flavor to Mar. She could change her religion and lifestyle, but she couldn’t reverse all the damage she’d done to her body.

The Taste

The lunch at Khadijah’s house encouraged her to learn to cook. Not Arabic food like Layth did – that was too far outside her realm of experience. Since she practically survived on frozen burritos, she decided she’d start by making her own. Her early efforts were basic – beans, cheese, guacamole and pico de gallo in a lightly toasted tortilla. She bought a Mexican cookbook, purchased halal beef and chicken at the Middle Eastern market, and experimented with preparing dishes like carne asada seasoned with simple spices; and shrimp burritos with spicy black beans, rice, tomatoes and cilantro.

Weeks passed. She continued cooking, and serving at the masjid. Nights in the apartment – even with her Islamic lectures, Quran and sci-fi novels – could be lonely. Not always. Just on certain nights, when the old nicotine craving hit, and the shadows in the corners felt deeper. A person needed someone to talk to, sometimes.

Three months after Ramadan ended, Mar was grilling fish to make Baja-style fish tacos. She was on lecture 61 of the seerah series, and as she cooked, she noted how good the food smelled, with the savory scent of fish and grilled onions filling the apartment.

Smelled. The food smelled. She stepped back from the stove and stared at the sizzling pan. She could smell the food! Hurriedly, she took the fish off the stove, assembled a taco with a corn tortilla, cabbage, pico de gallo and mayonnaise, and took it to the little kitchen table. Blowing on the taco to cool it, she took a bite.

The flavor nearly knocked her over in her chair. It was intensely spicy and salty, more than anything she ever remembered eating. It was as if she had never tasted food before. She burst into tears, and had to spit the food onto the plate, as she was crying so hard. Pushing back from the table, she fell into sajdah on the floor. She remained in sajdah for a long time, praising Allah.

When she finally recovered from the shock, she devoured four fish tacos. At moments tears came again to her eyes, and at other moments she laughed.

A Bad Day

Bad day at work. For some reason the nicotine craving had reared its monstrous head last night and she couldn’t shake it loose. She’d barely slept. Today, she found herself making the old little motions – reaching for the lighter in her pocket, and even lifting her fingers to her mouth. The craving was not physical – she no longer experienced withdrawal symptoms. Rather, it was as if the craving had been imprisoned in some dusty corner of her mind, and the prisoner was now making a last-ditch effort to break out and take over.

Dark thoughts fluttered in her mind. How disappointed her mother had been with the mess Mar had made of her life. Her husband, a good man who’d begged her to quit smoking, until she snapped at him to love her as she was, or hit the road. He chose the road. Her aged body was certainly damaged from those decades of smoking, and though she could reverse some of that, she knew she had shortened her lifespan.

Stepping into the break room to get a cup of coffee, she saw Damon and two others clustered together, watching a video on someone’s phone. Damon was a young African-American man who dressed in slacks and colorful shirts, and wore his hair in short dreadlocks. Mar thought – thought she couldn’t be sure – he was the one who’d made the “wicked witch” comment.

“Damn!” Damon said. “You see that? He knocked that boy into the next century.”

Before her Islam, Mar would have berated Damon, called him a slacker, and threatened to fire him. She felt some of that petty resentment now.

“Damon!” she snapped.

The young man jumped. He stuffed his phone in his pocket and said, “I know, I know, get back to work.” There was genuine fear behind his words, but also a trace of contempt.

Mar’s face flushed. I’m not that person anymore, she reminded herself. And Damon was one of her best workers. She cleared her throat. “No. I was going to say that your work was great last month. There will be a bonus for you in this month’s paycheck.”

“Oh! I… don’t know what to say. I mean, thanks.”

“Go ahead,” Mar said. “Watch your video, it’s fine.”

The Request

She started taking more than baked goods to the converts meetings. She’d take halal enchiladas and a tray of cupcakes, or calabacitas – zucchini and corn topped with melted cheese – and homemade oatmeal cookies. She was still focused on service – setting up, and cleaning up. She’d gotten used to it, and found it rewarding in its own right.

New sisters came into the community. Some had recently moved to the city, and others were new converts. Yet, strangely, they avoided her as well. When Juana was there she always planted herself right at Mar’s side, but she was a busy woman and didn’t always attend. Once or twice Khadijah showed up, and those were good nights.

One evening a new sister, a young African-American convert named Abida, approached her, munching on one of Mar’s black and white cookies.

“As-salamu alaykum,” Abida said. “I just want to say… the food you bring every week? It’s amazing. I don’t know if you noticed, if there are any leftovers I always make myself a plate to take home. I hope that’s okay.” She gave an embarrassed laugh. “I don’t know how to cook. I just want to thank you. I mean, you cook, you volunteer, you do everything. You inspire me.”

Mar gaped in shock, then recovered her wits enough to say, “I’m so glad. Of course, you’re welcome to the leftovers.”

“Do you think we could have lunch sometime? I feel like you’re a good person to know.”

Mar smiled so widely it almost hurt her face. “Sure. I’m free on the weekends.”

“How come…” Abida gave an embarrassed wince. “How come you always sit alone?”

“You tell me. You avoid me like everyone else.”

“Oh!” Abida’s face fell in dismay. “I saw everyone else giving you space and just thought you were a very private person.”

Mar smiled. “No, that’s not it. They think I’m dirty.” Her eyes flicked to Swiyyah, the woman who’d asked her if she’d washed her hands before making the food. Swiyyah sat with a knot of other sisters, laughing about something.

Abida’s mouth fell open. “What?”

“I used to smoke heavily. The cigarette smoke made me smell bad. A rumor went around that I was dirty.”

To Mar’s amazement. Abida actually brushed a tear from her eye.

“That’s the worst thing I ever heard,” the young woman said, then gave Mar a tight hug.

A New Skin

Another Wednesday night. Mar put on some perfume oil, and took an Uber. The driver glanced at her in the rear-view mirror. “You smell good,” he said.

Mar smiled. “Thanks.”

She had outdone herself today, making Sonoran cheese soup, and chile rellenos stuffed with beef and tomatoes. She was really starting to get the hang of northern Mexican cooking, especially since she could now taste what she prepared.

She sat at a table with Juana on her left, and Abida on her right. Abida had linked her arm with Mar’s, and Mar was very aware of it. The gesture meant a lot to her, but no one had touched her in a long time, and a part of her was uncomfortable. She ignored that part, and cinched her own arm tighter around Abida’s.

The lecture was over, and Mar took a foil-wrapped packet of semi-sweet chocolate chip cookies out of her purse. She had planned to give them to Khadijah, but the elegant Southern sister was not here. So instead she shared them with Juana and Abida.

A sister approached. It was Swiyyah.

“Do you think I could sit with you?”

Juana pulled out a chair. Swiyyah sat, then turned to Mar. “I’m so sorry. I’m ashamed of what I said. Please forgive me.”

Mar wanted to say… actually, to her surprise, there was nothing bad she wanted to say. She pushed the packet of cookies across to Swiyyah, watching her with an unflinching gaze. Swiyyah snatched one of them up, took a bite, and widened her eyes. “Uhh, so good, mashaAllah.”

A smile spread over Mar’s face. She felt like a snake shedding an old skin. The rough, protective skin sloughed away, leaving a new skin that was soft and gleaming. Even so, she reminded herself not to get too attached to this feeling. “Renounce what the people possess,” she told herself. “Chasing approval is like chasing your own shadow.”

Still, it felt good to have friends.

A Picnic by the Sea

On a Saturday six months after Ramadan, she packed the food into a backpack and took the bus all the way to Ocean Beach. Not Mexican food this time. Just flatbread, cheese, olives, sliced cucumbers, a small container of hummus she had made herself, and a row of oatmeal cookies wrapped in wax paper. She carried a thermos of water and her prayer rug rolled tight beneath her arm.

There was no fog, and the afternoon sun lay golden on the sand. The wind was steady but not harsh, carrying the smell of salt and kelp, and whipping her green dress around her legs. The Pacific stretched away in a sheet of hammered silver, the long lines of surf advancing and collapsing with a sound like the breath of a great beast.

She spread her blanket on one of the dunes at the top of the beach, where she had a long view in each direction. Even in the sun it was a bit chilly. She zipped up her brown cotton jacket, and adjusted the black scarf that concealed her thick blond hair.

The first bite of bread and cheese made her close her eyes. Flavor flooded her mouth: salt, cream, and the sharp green of the olives. She was still not used to how bright and strong everything tasted. Had it been like this when she was young? She couldn’t remember.

She’d seen a doctor, and he said that her lungs were surprisingly healthy, considering. She’d done real damage, but she had also given herself a chance at a future.

When she thought about the woman she’d been before – poisoned, ugly, bitter and alone – it made her grimace. Allah had freed her from that, for reasons she could not understand. It was said that in Jannah everyone would receive a body that would not suffer or age. Sometimes she felt Allah had given her a preview of that mercy here on earth.

For a while she did nothing but eat, watch the waves and feel the air moving across her face. Gulls wheeled overhead, crying out. Far down the beach a child ran after a ball.

A movement to her left caught her eye. A woman had come down to the beach with a large horse on a lead. The horse was chestnut brown with black legs and a white spot on its forehead. The magnificent animal’s coat shone like wet ink in the sun. It stepped delicately at first, ears flicking, nostrils wide as it took in the smells of the ocean.

The woman walked the horse to the edge of the water, then paused and unclipped the line.

For a heartbeat nothing happened.

Then the horse went from stillness to motion so suddenly that Mar’s breath caught in her chest. It leaped forward and broke into a full run along the waterline, hooves pounding the packed sand, mane whipping behind it like a dark banner. The sound of its gallop rolled over the surf.

Mar pushed herself to her feet without realizing she had moved. A cry escaped her throat — not a word, just a sharp sound of astonishment that she could not contain.

The horse ran as if the world had fallen away behind it. Children shouted and pointed. A dog bounded after the horse, barking, and was left behind in seconds. Two other horses stood farther down the beach, held on their leads; the black horse slowed as it approached them, tossing its head in greeting, its chest heaving. For a moment it seemed it might stop.

Then it chose the open shore instead. It surged forward again, muscles gathering and releasing in long, fluid strides, running until it was a dark shape against the glittering edge of the sea.

Mar stood with her hands pressed to her mouth. She felt the deep pull of breath, the expansion and release, and with it came the memory of all the years when she had not been able to breathe.

The horse turned at last and came back at a slower pace, its flanks rising and falling. The woman caught it gently and laid her hand against its neck. The animal stood trembling, alive with its own power.

Mar lowered her hands, then eased herself back onto the blanket. At that moment there was nothing she needed but the pleasure of Allah. No craving gnawed at her, no chains bound her. The wind tugged at her hijab while the sun was warm on her cheeks. The woman and the black horse walked away along the waterline. Somewhere out to sea, a ship’s horn boomed.

A seagull landed nearby and eyed her, enticed by the smell of her picnic basket. Mar took out one of the oatmeal cookies, and the seagull hopped closer. She smiled, tossed the bird a chunk of cookie, and took her own bite. The sweetness was rich on her tongue. She closed her eyes, and took a deep breath.

THE END

* * *

Come back next week for another short story InshaAllah.

Reader comments and constructive criticism are important to me, so please comment!

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories on this website.

Wael Abdelgawad’s novels – including Pieces of a Dream, The Repeaters and Zaid Karim Private Investigator – are available in ebook and print form on his author page at Amazon.com.

Related:

Cover Queen: A Ramadan Short Story

Impact of Naseehah in Ramadan: A Short Story

The post NICOTINE – A Ramadan Story [Part 2] : Cold Turkey appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

. With two weeks already behind us, we may be reassessing our Qur’anic goals. Are we behind? If yes, by how many pages? We may readjust these figures accordingly and move on with the new plan. But is that all?

. With two weeks already behind us, we may be reassessing our Qur’anic goals. Are we behind? If yes, by how many pages? We may readjust these figures accordingly and move on with the new plan. But is that all?

would sometimes recite

would sometimes recite

was sitting next to the Prophet

was sitting next to the Prophet