Islamic History Month Canada: A Bookish Roundup

October is Islamic History Month in Canada, federally recognized since 2007 as an opportunity to “to celebrate, inform, educate, and share with fellow Canadians the rich Muslim heritage and contributions to society.” This year’s theme is “Pioneering Muslim Communities in Canada,” learning about and giving homage to those in our communities who first established Islam in these lands. From small islands to sprawling urban centers, every Muslim community in Canada started with at least one person who believed in Allah  and created space for fellow believers to come together and build upwards.

and created space for fellow believers to come together and build upwards.

In addition to the pioneering history of Muslims in Canada, we must consider more recent history as well: the realities of Muslims in a post-9/11 world, contending with the surveillance state, illegal detention and torture, and ongoing harassment of Muslims in Canada. Figures such as Maher Arar and Omar Khader must have their stories remembered, and lessons learned from, on just how fraught our existence as Muslims in Canada truly is. The work of people like Monia Mazigh must never be forgotten, as it is the work that so many of us will need to draw from in our own confrontations with state-led Islamophobia.

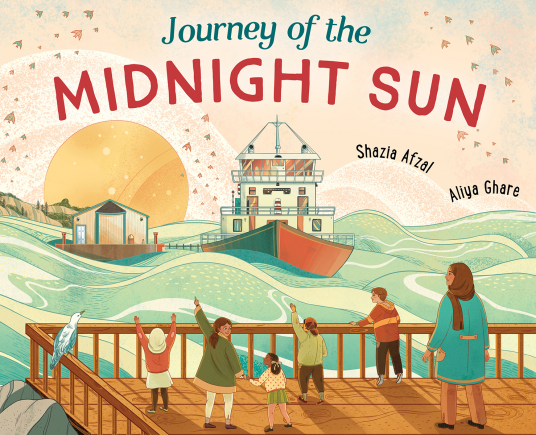

– Journey of the Midnight Sun by Shazia Afzal

In 2010, a Winnipeg-based charity raised funds to build and ship a mosque to Inuvik, one of the most northern towns in Canada’s Arctic. A small but growing Muslim community there had been using a cramped trailer for their services, but there just wasn’t enough space. The mosque travelled over 4,000 kilometers on a journey fraught with poor weather, incomplete bridges, narrow roads, low traffic wires, and a deadline to get on the last barge heading up the Mackenzie River before the first winter freeze.

In 2010, a Winnipeg-based charity raised funds to build and ship a mosque to Inuvik, one of the most northern towns in Canada’s Arctic. A small but growing Muslim community there had been using a cramped trailer for their services, but there just wasn’t enough space. The mosque travelled over 4,000 kilometers on a journey fraught with poor weather, incomplete bridges, narrow roads, low traffic wires, and a deadline to get on the last barge heading up the Mackenzie River before the first winter freeze.

This stunning picture book makes the perfect Islamic History Month storytime choice!

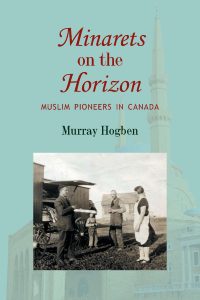

– Minarets on the Horizon by Murray Hogben

This book gives us a detailed look at the Muslim presence in Canada, starting with the pioneer settlers from Syria/Lebanon and the Balkans in the early twentieth century and moving on to the more modern midcentury arrivals from South Asia and Africa. Told in their own words, the stories in this collection give us a rare insight into the lives of these pioneer Muslims.

This book gives us a detailed look at the Muslim presence in Canada, starting with the pioneer settlers from Syria/Lebanon and the Balkans in the early twentieth century and moving on to the more modern midcentury arrivals from South Asia and Africa. Told in their own words, the stories in this collection give us a rare insight into the lives of these pioneer Muslims.

Punjabi men in the timber mills of British Columbia; Lebanese Arab peddlers on foot or horse cart on the rural highways of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba; men venturing north on dog sleighs to trade for fur; young women arriving to start families and soon to become family matriarchs; shopkeepers serving small provincial towns and big cities; and finally, students and professionals arriving in the postwar urban centres.

Wherever they went, they bore the brunt of xenophobia and acknowledged kindnesses, as they adapted and sought out fellow worshippers and set up community centres and mosques.

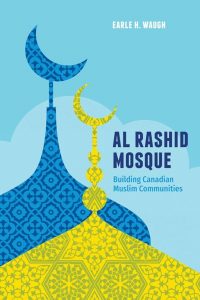

– Al-Rashid Mosque: Building Canadian Muslim Communities by Earle H. Waugh

– Al-Rashid Mosque: Building Canadian Muslim Communities by Earle H. Waugh

Al Rashid Mosque, Canada’s first and one of the earliest in North America, was erected in Edmonton in the depths of the Depression of the 1930s. Over time, the story of this first mosque, which served as a magnet for more Lebanese Muslim immigrants to Edmonton, was woven into the folklore of the local community.

Edmonton’s Al Rashid Mosque has played a key role in Islam’s Canadian development. Founded by Muslims from Lebanon, it has grown into a vibrant community fully integrated into Canada’s cultural mosaic. The mosque continues to be a concrete expression of social good, a symbol of a proud Muslim Canadian identity. Al Rashid Mosque provides a welcome introduction to the ethics and values of homegrown Muslims. The book traces the mosque’s role in education and community leadership and celebrates the numerous contributions of Muslim Canadians in Edmonton and across Canada.

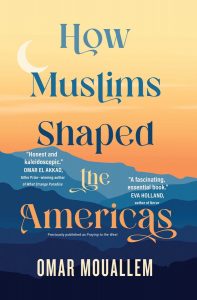

– How Muslims Shaped the Americas by Omar Mouallem

– How Muslims Shaped the Americas by Omar Mouallem

In How Muslims Shaped the Americas, Mouallem explores the unknown history of Islam across the Americas, traveling to thirteen unique mosques in search of an answer to how this religion has survived and thrived so far from the place of its origin. From California to Quebec, and from Brazil to Canada’s icy north, he meets the members of fascinating communities, all of whom provide different perspectives on what it means to be Muslim. Along this journey, he comes to understand that Islam has played a fascinating role in how the Americas were shaped—from industrialization to the changing winds of politics.

Despite my distaste with the author himself, this book does an excellent job of exploring both Al-Rashid Masjid and the Midnight Sun Mosque (the very same one from the picture book!), as well as pausing to pay homage to the victims and survivors of the Quebec City Mosque Massacre in Grande Mosquee de Quebec.

– Hope & Despair: My Struggle to Free My Husband, Maher Arar by Monia Mazigh

– Hope & Despair: My Struggle to Free My Husband, Maher Arar by Monia Mazigh

This book traces the inspiring story of Monia Mazigh’s courageous fight to free her husband, Maher Arar, from a Syrian jail. From the moment Maher Arar, a Canadian citizen, was disappeared into the bowels of Bashar al-Assad’s dungeons, Monia Mazigh worked tirelessly against the Canadian government, security intelligence agencies, and media to bring her husband home and get him justice.

She began a tireless campaign to bring public attention and government action to her husband’s plight, eventually resulting in his release and return to Canada. Arar and Mazigh’s story is a chilling reminder to all Canadian Muslims of the realities of living under systemic Islamophobia, and is an important lesson to us all on resisting and holding our government accountable.

– Systemic Islamophobia in Canada: A Research Agenda

Systemic Islamophobia in Canada presents critical perspectives on systemic Islamophobia in Canadian politics, law, and society, and maps areas for future research and inquiry. The authors consist of both scholars and professionals who encounter in the ordinary course of their work the – sometimes banal, sometimes surprising – operation of systemic Islamophobia. Centring the lived realities of Muslims primarily in Canada, but internationally as well, the contributors identify the limits of democratic accountability in the operation of our shared institutions of government

– Under Siege: Islamophobia and the 9/11 Generation by Jazmine Zine

– Under Siege: Islamophobia and the 9/11 Generation by Jazmine Zine

Under Siege explores the lives of Canadian Muslim youth belonging to the 9/11 generation as they navigate these fraught times of global war and terror. While many studies address contemporary manifestations of Islamophobia and anti-Muslim racism, few have focused on the toll this takes on Muslim communities, especially among younger generations.

Covering topics such as citizenship, identity and belonging, securitization, radicalization, campus culture in an age of empire, and subaltern Muslim counterpublics and resistance, Under Siege provides a unique and comprehensive examination of the complex realities of Muslim youth in a post-9/11 world.

This Islamic History Month, Canadian Muslim communities should take the time to honour our pioneering members, teach our youth about the Islamic history of Canadian Muslims, and educate ourselves on how to navigate living in this country that remains riddled with systemic Islamophobia.

Related:

From the MuslimMatters Bookshelf: Black (Muslim) History Month Reads

The post Islamic History Month Canada: A Bookish Roundup appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.