On a Ramadan afternoon, a stressed Muslim man nearly runs over a young Sikh—and learns a lesson about gratitude, and what makes a life truly blessed.

* * *

1. You’ll Sing And You’ll Cry

It was a late Saturday afternoon in Ramadan, and Hamza was in a foul mood as he sped through the parking lot. Driving his Lexus, he gunned the gas, searching for a free space near the grocery store. In his pocket was a long shopping list his wife had given him.

As if he didn’t have better things to do. His boss was pressuring him with more work every day, multiple bills were due with insufficient money to pay them, and his marriage was coming apart. Maybe coming apart was too strong, but his wife May, who he loved like a tree loves the sun, was increasingly distant. One by one they’d given up on all the things they used to enjoy doing together, until their shared life had shrunk to a single evening meal and a shared bed.

In normal circumstances all of this would be depressing, but in Ramadan – when he was hungry, sleep-deprived and running on fumes – it made him angry and bitter.

Then, the fact that he was angry and bitter in Ramadan made him feel hopeless, because this was a sacred month. It was supposed to be a time of sacrifice, healing, and familial togetherness. What was wrong with him? Was he the only one who experienced Ramadan this way?

His father, a stocky Pakistani Punjabi with a beard like a horse’s mane, used to say, “Gaana te rona sabh nu aunda ae.” You’ll sing and you’ll cry. That is human.

Truer words had never been spoken.

2. An Argument

He turned a corner and swerved around a car trying to back out of a parking space. The car honked at him, and he gave it an annoyed flick of his hand. He sped past the dollar store, the pet store, and the drug store. As he approached the pot store – a fancy dispensary that sold art along with marijuana in various forms – a tall young man wearing a turban stepped out of the store and straight into the road.

Hamza jammed his foot onto the brake pedal, skidding to a stop barely a few feet from the man’s legs. Before he even knew what he was doing, he flung open the car door and leaped out, hands balled in fists.

“Hey! I almost ran over you! Are you blind?”

The man, a Sikh with dark brown skin and a long black beard, looked Hamza over slowly. He was thin, and wore a dark blue track suit and white sneakers. A slow smile spread over his face.

“Naw, man. I’m high.”

Hamza’s face twisted in outrage. “What is wrong with you? Do you have a car? Are you driving in this condition?!”

The Sikh shrugged. “What’s wrong with you?” He spoke slowly, like he was half asleep. “You drivin’ like your car’s on fire. Takes two people to have a fight.”

Hamza took a deep breath and let it out. Ramadan, he reminded himself. Remember Allah.

“You know what?” he said. “I’m fasting.”

The Sikh shrugged again. “So what? I’m high.”

“That’s your problem. I’m fasting.”

“And I’m high.”

Hamza gestured to the Sikh’s turban. “You’re Khalsa Sikh, right? Aren’t drugs against your religion?”

The Sikh studied him. “And you’re Muslim, right? You a walking paragon?”

Hamza threw up his hands in exasperation. “Get your act together.”

He returned to his car and drove slowly until he found a parking spot. Shutting off the engine, he sat in the car. His calves were trembling, not with anger but with fear. If he’d been a second slower… He imagined the sound of the impact, the Sikh’s body flying, the blood on his car. “Astaghfirullah,” he said, closing his eyes. “Astaghfirullah.”

3. A Chance Encounter

Three days later, May sent him to a Pakistani restaurant to pick up a few trays of food. They had guests coming over for iftar in a few hours. He was tired. He’d been fasting and working all day long. He was an electrical engineer working for a company that designed lighting systems. There were very few firms in their particular area of specialization. Demand was high, and the work mounted every day. Right now, they were designing a system for a new delivery warehouse, and the pressure to complete it on time was immense. Once his guests left tonight, he would have to return to the office, no matter how exhausted he was.

The pay was good, but he wasn’t sure how much more he could take.

The only bright spot was something his wife had done that day. When Hamza had been about to leave the house to pick up the food, she’d stopped him and caressed his shoulder. “Allah bless you,” she said in Punjabi. “You do so much for us.”

It had nearly made Hamza cry.

Now, entering the restaurant, his eyes passed over the few customers. Normally, this place was full of Muslims chowing down, but it was daytime in Ramadan, so the only diners were a young American couple and a tall young Sikh sitting by himself by the window, eating a plate of sag paneer and a side of samosas. Hamza’s steps slowed as he took in the Sikh’s black turban, jeans, and sneakers. The man wore a Led Zeppelin concert t-shirt, and his black beard nearly touched his chest.

It was him. The very same man Hamza had almost run over.

On impulse, not knowing why he was doing it, Hamza walked up to the man, pulled out a chair, and sat at the small table.

The Sikh looked up, frowning as he chewed. “I know you?”

Hamza looked the man over. His skin was dark, and his nose pronounced, with a slight hook. He wore a steel bracelet on one wrist. His eyes seemed alert – not sleepy, like the other day.

“I guess you’re not on drugs today,” Hamza said in Punjabi.

The man’s frown deepened. “Your Punjabi sounds weird. Are you Sikh?”

“I’m Pakistani Punjabi. I’m Muslim.”

“Oh.” The Sikh nodded in a friendly way. “Cool. So what’s up?”

4. The Conversation

“You don’t remember me at all, do you?”

The Sikh tipped his head to one side, studying Hamza. “Are you on one of the cricket teams? I played against you?”

“I nearly ran you over the other day.”

The Sikh snapped his long fingers. “Gotcha! The angry fasting guy.”

Hamza felt a flush of embarrassment. Those two states of being – angry and fasting – weren’t supposed to go together.

“Yeah, um. Sorry about that. I was driving too fast. I was…” He shrugged. “Stressed out. Upset.”

“My fault too,” the Sikh said. He gestured to the smaller plate. “Have a samosa. They’re good here. Crispy on the outside, but not heavy.”

Hamza waved a hand. “Thanks, but I’m fasting.”

“Still?” The Sikh was incredulous. “Don’t you ever eat?”

Hamza laughed. “After sunset.”

“You want a drink at least? I’ll get you one. What do you want?”

“Can’t drink either.”

“Whoa. That’s dedication, bro.”

Hamza shook his head slowly. “Except I’m blowing it. It’s supposed to elevate me spiritually, but I’m just irritated and on edge.” He lifted a hand, then let it flop onto the table. “I don’t even know why I’m telling you this.”

“What are you on edge for? Can’t be money, I saw that sweet ride of yours.”

“Work. Home life.”

“You’re married?”

Hamza nodded. “Love of my life. Most beautiful woman in the world.”

The Sikh laughed, then punched Hamza in the shoulder as if they were old friends. “Waheguru ji da shukar hai. Thank God for that.”

Hamza smiled. “Yeah. You’re right.”

The Sikh took a bite of the sag paneer. “Sorry about eating in front of you. I’m hungry.”

Hamza laughed. “It’s a restaurant.”

The Sikh chewed. “You own your own home?”

“Getting kind of personal, but yes.”

5. Sikh Wisdom

“Well then.” The Sikh clapped his hands together, then spread them out wide. “What are you stressed about? Banday di khushi chaar cheezaan vich hundi ae: changi biwi, khulla ghar, changa padosi, te changi sawari. That’s Sikh wisdom for you.”

Hamza smiled. “That’s not Sikh wisdom, that’s a hadith.”

“A what?”

“A saying of the Prophet Muhammad. Four things are part of happiness: a righteous spouse, a spacious home, a righteous neighbor, and a comfortable mount.”

“Doesn’t surprise me,” the Sikh said. “There’s a lot of Islam in Sikhism. Point is, you’re blessed, brother. The wife, the house, the ride. You have all the goodness of this world. I don’t have none of that. Nothing. Why do you think I get high? Because I’m a failure.”

“I’m sure it’s not that bad.”

The Sikh nodded grimly. “Yeah. It is.”

“Maybe you should get off the weed.”

The Sikh gazed at him coolly. “Maybe so. I only started recently, when our product failed.”

“What product?”

“I’m a game designer. Spent three years working for a startup, building a single game. My UI was gorgeous, I’ll tell you that. But the programming had fatal flaws – that was Anika’s responsibility, our co-founder – and we ran out of funding. Three years wasted.”

“That’s rough.”

“But I’ll tell you what. I wouldn’t care about anything else if I just had a good woman.” He grabbed a samosa and held it up in the air. “That’s the golden heart of existence, right there. The love of a sincere woman.” He rotated the samosa one way and another as if it were a shining gold nugget he’d just pulled out of the earth.

“Speaking of women.” Hamza tapped the table twice. “I have to pick up this food and get home.” He stood.

“Hold up,” the Sikh said. “Take my number. Come play cricket with us sometime.”

They exchanged numbers. The man’s name was Jagdeep, but – he said – people called him Jag. After a quick goodbye and a handshake, Hamza retrieved the food May had ordered and headed for home. He was very hungry, and the smell of the food made his mouth water. Yet he felt more relaxed than he had in weeks.

“The golden heart of existence,” Jag had said, with a samosa in his hand. Hamza laughed thinking of it.

6. Homecoming

As he walked into the house, balancing the two large trays, his wife called from the kitchen.

“What took you so long? It’s only a half hour until iftar. Our guests will be here soon.”

He set the trays on the kitchen counter. The kitchen was redolent with the scents of chicken karahi, creamy lentils, and basmati rice. He saw that May had also made an onion salad and spiced roti.

“I ran into someone.”

“A friend?” May pulled two jugs of juice from the fridge – guava and mango – and handed them to him. “Put these on the table.”

Hamza regarded her. May was studying for her master’s in education. After being in class most of the day, she had hurried home to prepare this meal. She was perfectly dressed, and wore her best gold bracelets and earrings. But her eyes were red, and her face was drawn.

Hamza set the juices down on the counter, then pulled May into his arms. He embraced her tightly – more tightly than he had in a long time – then gave her a kiss and released her.

May broke into tears. “Why did you do that? Now my makeup is messed up.”

He took her hand and kissed it. “Because you are the golden heart of my existence.”

More tears. She smacked his shoulder. “Stop it, you dummy.” She retreated to the bathroom.

They busied themselves preparing the table. The guests arrived, and when Maghreb time came all broke their fasts. Hamza set prayer rugs down in the living room. Some of the men were older than him, but they insisted that he, as head of the household, lead the prayer.

Later, as they sat around the dining table eating, Hamza’s eyes kept returning to May. Her back was straight, and her face shone. He hadn’t seen her this happy and carefree in a long time. Once, as he watched her, she looked his way. Seeing him watching her, she blushed like a newlywed.

Holding his phone under the table, Hamza texted his boss: “Can’t make it back to work tonight. I need a little break.”

The phone buzzed in his pocket a minute later. Expecting a rebuke from his boss, he saw instead that it was a message from Jag.

“You eating now?”

“Yes,” Hamza replied.

“Respect.”

Smiling, Hamza slipped the phone back into his pocket, and reached for another piece of roti.

THE END

* * *

Come back next week for another short story InshaAllah.

Reader comments and constructive criticism are important to me, so please comment!

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories on this website.

Wael Abdelgawad’s novels – including Pieces of a Dream, The Repeaters and Zaid Karim Private Investigator – are available in ebook and print form on his author page at Amazon.com.

Related:

Cover Queen: A Ramadan Short Story

Impact of Naseehah in Ramadan: A Short Story

The post The Sikh – A Ramadan Short Story appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

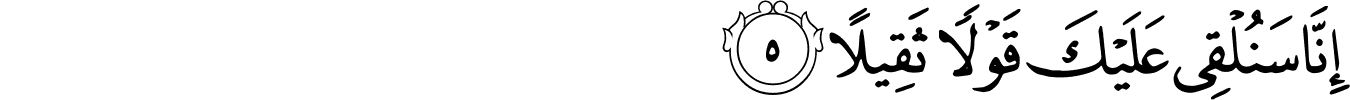

. With two weeks already behind us, we may be reassessing our Qur’anic goals. Are we behind? If yes, by how many pages? We may readjust these figures accordingly and move on with the new plan. But is that all?

. With two weeks already behind us, we may be reassessing our Qur’anic goals. Are we behind? If yes, by how many pages? We may readjust these figures accordingly and move on with the new plan. But is that all?

would sometimes recite

would sometimes recite

was sitting next to the Prophet

was sitting next to the Prophet