A day of prayer, work, and long-buried family truths ends with Darius left behind, wondering what he is not being told.

Read Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

* * *

Darius’s First Prayer

As ordered, I rose at dawn without prompting – I could almost hear my own cow back home calling, wanting to be milked – and dressed to tend to the morning duties.

As I walked toward the door, Haaris took my hand to stop me. “Not yet,” he said. “We have to pray Fajr.”

I had no idea what he was talking about, but Zihan Ma entered from the front door, sleepy-eyed, but with his face and beard dripping water. He said gently, “Make wudu’. Haaris, show him how.”

Haaris led me out into the cold, to the outhouse. It was a long walk, as the outhouse was on the edge of the property next to the safflower fields, in an area where the land sloped downhill. There was a hedge planted in front of it, shielding it from view, and I saw that there were actually two of them. Haaris explained that it was a twin-pit system, in which one pit was allowed to decompose while the other was in use. When fully decomposed, it would be emptied and the waste would fertilize the fields. The latrines stank a bit, of course, and flies buzzed about. That was normal.

We relieved ourselves, then walked back to the house. On the western side of the house there was an open space with clothes lines strung up. The well was there, surrounded by a circle of flat stones, and with a large stone basin beside it. Using a ladle to scoop the water, Haaris showed me how to wash my hands, mouth, nose, face, arms, hair, ears and feet.

“You do this every morning?” I was amazed, for I had typically not bathed more than once every three or four days.

“More than that,” Haaris said.

Inside, a large bamboo fiber mat had been laid down in the living room. We arranged ourselves in a formation, with Ma Shushu in front, myself and Haaris behind him, and Lee Ayi behind us. I understood that we were about to begin a religious ritual of some kind. Lee Ayi had assured me that they did not pray to statues, and that was obvious, as there was no statue in sight. According to her, they prayed to Allah, an eternal, all-powerful being.

“What if I am not yet ready to participate in this ritual?” I asked.

Ma Shushu gazed at me solemnly. “Nothing will happen. There is no compulsion in religion. You will still be a part of the family.”

I remembered my father’s words: “The only one to worship is Allah.” He had not explained, but my heart told me that if he were here, he would not object to this ritual, even if he himself did not participate. I exhaled, feeling my chest relax. “I will pray with you. But I don’t know what to do.”

“Just imitate Haaris’s movements for now. We will teach you the words later.”

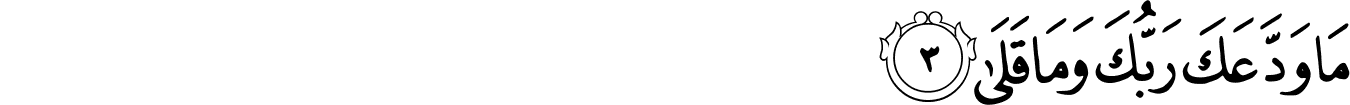

I raised my hands as Haaris did, and Ma Shushu began to recite. The words were foreign, but his voice was deep and pleasant, and the rhythm of the chanting was hypnotic. I felt myself falling into River Flow, just as I did when practicing Five Animals. We bowed, stood, prostrated, sat, prostrated, and stood again. At one point we looked right and left, and I did not know the prayer was finished until Ma Shushu turned in his place and sat cross-legged.

“How do you feel?” he asked me.

I felt close to tears, was the truth. All those times I had stopped and watched the people in the temple, and felt envious of them in spite of their stupidity, and felt a pull to join them – now I understood why. I felt small and humble, but not humiliated, and certainly not stupid. Rather I felt elevated, not in a literal sense, but as if my heart had grown in my chest. I could not express any of this, and in the end I only said, “I feel calm.”

Ma Shushu nodded. “That is a good way to feel.”

Women’s Work

I was prepared to go out and start the farmwork, but Ma Shushu stopped me. “Not yet. Your shoulder is not ready. Only light housework for now.”

First I swept the entire house. Then Lee Ayi set me to work at the low table near the window, where the morning light poured in, deep and yellow. I sifted a huge sack of rice to remove small stones, and when that was done I shelled peanuts into a clay bowl, the dry skins crackling softly between my fingers. I worked quickly but methodically, not missing anything. My shoulder still ached, but the work was slow and did not strain it.

The scent of the peanuts reminded me of home, and I found myself missing Far Away and Lady Two. My poor cat. Where was he now? Running from house to house at night, pawing through the garbage for a scrap? A dairy cow was valuable, someone would always care for her. But a stray cat with no parents who loved him, no home, no job? They would throw stones and chase him away. I sighed.

“What’s wrong?” Lee Ayi asked as she rinsed a pile of vegetables.

I shook my head, saying nothing.

Outside, I could hear goats bleating and the dull thump of hooves, the steady noises of a working farm that went on without me.

Lee Ayi moved quietly in and of the room, taking the vegetables outside to dry on woven trays, and lifting lids to check simmering pots. Every so often she glanced at me, not to hurry me, but to be sure I was not favoring the wounded arm too much.

“You work like your father,” she said at last.

I looked up, startled. “Is that good or bad?”

She smiled faintly. “Both.”

She sat across from me and began stripping safflower petals from their heads, her fingers quick and practiced. The petals fell into a shallow basket like small flames.

“I feel bad,” I said, “that I am doing women’s work, while Haaris is outside by himself.”

Lee Ayi gave an annoyed click with her tongue. “There is no men’s work and women’s work. There is only work. All work holds dignity. A cook and a floor sweeper are no less dignified than a horse trainer or an army general. As Muslims, we serve Allah by serving humanity. When you work to benefit others you are working for Allah, and that is the highest calling.”

This was a foreign concept to me. What did humanity have to do with me? My father had never believed in serving anyone nor benefitting anyone except himself, me and my mother. Perhaps a compromise would be to understand it as service to family. By serving this family, I served Allah. I could accept that.

Highway Robbery

“Yong was always restless,” Lee Ayi said, as if reading my mind. “Even as a boy. Cai Lee tried to beat it out of him. It did not work. The harder Father pushed, the more Yong pushed back.”

I said nothing. I had never heard my father spoken of as a child.

“He had no patience for books,” she went on. “Nor for rules. The only things that ever held his attention were fighting and gambling. Martial skill came to him as easily as breathing. Gambling too. He was very lucky. Or perhaps very cursed.”

Her mouth tightened briefly, then relaxed again.

“He never cared for religion. Not even a little. When he began drinking as a teenager, Father said enough was enough. He cast him out. No food, no money, no place by the hearth.”

She did not look at me as she said this, but at the safflower petals.

“I used to meet him in secret,” she said quietly. “I would bring him steamed buns, or rice wrapped in cloth. A few coins. He always said he would pay me back one day.”

She gave a short, humorless laugh. “He never did.”

I would have smiled at the ridiculous notion of my father paying anyone back for anything, but the image of him as a hungry youth wandering the roads sat badly in my chest. As my father had lived, so had I as well. Was that the curse my aunt spoke of? Would I pass the same curse on to my own children?

“One day,” she continued, “Yong came upon a carriage stopped on the road, surrounded by three thieves. Highwaymen. Atop the carriage sat a noble Hui family, the Shahs. Among them was their daughter, Shah Nur. She was sixteen years old and beautiful. Yong fell in love at first sight.”

I froze, watching Lee Ayi intently. Shah Nur was my mother. I had never heard this story before, nor did I know anything about my mother’s family.

Lee Ayi went on: “I suspect if not for the beauty of Shah Nur, Yong would not have interfered. But he took it upon himself to attack the highwaymen. He carried nothing but a staff, while the highwaymen were armed with swords. Yet Yong killed one of the robbers in seconds. Seeing this, your grandfather, Shah Zheng, dismounted and joined in, taking the dead robber’s sword. Between them they drove the other two off.”

It was easy for me to imagine my father doing that. In my mind I could picture the entire battle, and could describe precisely what moves Yong had performed. This was the only incident I’d ever heard of in which my father’s fighting skills had been used to help someone. I felt proud of him.

The Shahs

“The Shahs,” Lee Ayi went on, “are descended from Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas, the companion of the Prophet, peace be upon him, who brought Islam to our land. They are the most noble of us all, and the most wealthy, as they organize and finance huge caravans that carry goods from here to India, Persia and Turkey.”

“I saw a caravan once,” I enthused, pleased to be able to tell Lee Ayi something she did not know. “We passed it on the road from my family’s town to the city. It had fifty horse-drawn wagons, can you believe it? They were loaded up with textiles, spices, armor, pistachios, and other things I could not see. It was guarded by many men. I never thought there could be so many armed men outside of the army.”

“Did the wagons bear an emblem of a mountain peak surrounded by five stars?”

“Yes!” I grinned at her. “How did you know?”

“Those wagons belong to the Five Stars Trading Company. That is the Shah family’s company.”

I gaped. “One family owns all of that?”

“And much more. Anyway, Shah Zhen rewarded Yong well for saving their lives. It was more money than he had ever seen. It happened, however, that as he had fallen in love with Nur, she too was captivated by him. For the Shah family, such a match was out of the question. Yong was nominally Muslim, but he was a nobody, a lout. So Yong met with Nur secretly and convinced her to leave with him. It was madness. But she was young and brave, and ready for an adventure. They used the money to buy a farm in another town. They disappeared.”

She resumed stripping petals.

“After you were born, Yong came back only once, alone, to give us the news. But the Shah family had never stopped looking for Nur. They put a price on Yong’s head. He knew if he stayed, he would bring danger to us all. So he left again and never returned. We knew that you existed, but that was all.”

I set the last peanut into the bowl and rubbed my fingers together, brushing away the skins. A multitude of thoughts swirled in my head. I didn’t think my poor mother had gotten the adventure she dreamed of. My father had never been cruel to her, had never beat her, but neither had he been the loving husband she must have hoped for. He had a temper, he shouted at times, he went to town to drink and gamble, and he was in and out of jail as far back as I could remember. Our farmhouse was decrepit and non-productive, and we had been very poor. And now Shah Nur, daughter of a great and noble family, was buried in a small flower-lined plot behind an abandoned, broken-down farmhouse.

I must have been silent for a long time, because I found Lee Ayi beside me, rubbing my shoulder. “It’s okay,” she said. “What’s done is done. Your mother is with Allah, just as we all will be one day. The best thing you can do is remember her love for you. That is her legacy.”

I nodded. Feeling the need to defend Yong Lee, I said, “My father did better in the end. He changed.”

Lee Ayi nodded. “I believe it. He joined the army to provide for you. That was an act of love.”

My lower lip trembled at that, but I managed to stifle it.

Dhuhr

At that moment, Ma Shushu came in from outside, his arms and face again dripping water. “Time for Dhuhr,” he said simply.

We laid out the mats. Lee Ayi adjusted my cushion so I would not strain my shoulder. Haaris was still out in the fields, his voice carrying faintly as he called to the animals.

“What about Haaris?” I asked.

“He is tending to the animals,” Ma Shushu said. “He will pray on his own.”

I felt a flush of heat rise up my neck. The boy was outside working while I was in here, clean and sheltered, shucking peanuts and sifting rocks out of rice. I reminded myself of Lee Ayi’s words: All work holds dignity.

When the prayer was over, Ma Shushu – seeing my obvious embarrassment – said, “You will be back in the fields soon enough. Do not borrow tomorrow’s pride today.”

After prayer, we ate a simple meal. Rice, greens, a little salted fish. I ate slowly, forcing myself to be mindful.

Lee Ayi made a plate and asked me to take it out to Haaris. I found him in a wide, grassy field on the other side of the outhouses. I hadn’t even known this field existed. The scent of the grass was rich in my nostrils. Haaris sat on a boulder, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, holding a bamboo switch and watching the cows, donkeys, and goats as they grazed. His boots were dirty, and he looked tired. He accepted the plate eagerly and began to devour it.

“Watch the baby goat.” He indicated with the chopsticks. “It keeps trying to headbutt the calf.”

I squeezed in next to him on the boulder and watched. The goat was more than a baby – maybe six months old, I would guess, though my eye was unpracticed – while the cow’s calf was younger but much bigger. As I watched, the goat bleated loudly, reared up on its hind legs and aimed its forehead at the calf, which was busy grazing. At the last instant the calf moved its head to the side and the goat missed. Haaris laughed out loud, spitting a bite of green beans.

I smiled as well. “The goat is a fighter.”

“Say ma sha-Allah.”

“What is that?”

“Oh, it’s like, this is something good that Allah made.”

“Repeat it.”

Haaris repeated the phrase, and I did my best to pronounce it.

“I’d better get back,” I said.

“I’ll see you soon,” Haaris promised. “We have studies.”

Studies

I changed the sheets on the beds then took the food scraps – vegetable peels and such – out to the compost pile. Outside, the sounds of the farm went on. Inside, the day settled around me like a garment I was still learning how to wear.

A few hours later Haaris and I sat on woven mats in Ma Shushu’s study, the afternoon light slanting in through the window and laying a pale rectangle across the floor. A low desk stood before him, its surface worn smooth, with a stack of books neatly arranged at one corner. Haaris sat cross-legged beside me, already alert, his back straight and his hands folded in his lap as if lessons were a form of prayer in themselves.

Ma Shushu began with numbers.

He drew figures in charcoal on a wooden board, simple at first. Counting, grouping, dividing. Haaris answered quickly, eager to please. I was slower, unused to putting numbers to paper, but the logic of it came easily enough. When Ma Shushu shifted from grain tallies to weights and measures, I leaned forward without realizing it. This was useful knowledge. Real knowledge. The kind that kept accounts honest and prevented quarrels.

“Math is justice,” Ma Shushu said, tapping the board once. “If you cannot count, someone else will count for you, and it won’t be in your favor.”

After that came reading and writing. Haaris fetched brushes and ink while Ma Shushu laid out a sheet of paper. He wrote a single character and explained its strokes, the order, the balance. Haaris practiced carefully, tongue caught between his teeth. When it was my turn, my hand felt clumsy around the brush, but Ma Shushu corrected my grip without comment and had me try again.

“Slow,” he said. “Meaning comes from care.”

My father had taught me to read and write by drawing characters in the dirt, using the wooden training dao. I had literally grown up writing with a sword. However, I was not used to the brush, or the small scale. Once my hand became accustomed to the grip, and I learned to ease the pressure and make everything smaller, my hand began to flow. The brush whispered across the page.

“Have you done this before?” Ma Shushu asked. “You pick it up fast.”

“My father taught me using a – “ I stopped myself. “A stick.”

“A stick?” Ma Shushu sounded offended. He shrugged. “Well. Not everyone has resources.”

I stiffened for a moment, not sure if my father was being criticised. Then I took a breath and relaxed. I did not want to see my father and Zihan Ma as opposites or opponents. My father’s lessons in Five Animals had literally saved my life. Once, at the town fair, I had seen a relay race, where the teammates passed a red ribbon from one to the next. I imagined my father passing a ribbon on to Zihan Ma. I was that ribbon. That was my hope, anyway.

When the ink was set aside and the brushes rinsed, Ma Shushu poured water into three small cups. He drank first, then gestured for us to do the same.

“Now,” he said, “we speak of deen.”

Haaris shifted closer, his expression changing. This was his favorite part, I could tell.

Ma Shushu did not open a book. He rested his hands on his knees and looked at us, first at Haaris, then at me.

“All of it begins with tawheed,” he said. “The Oneness of Allah.”

He did not raise his voice or dramatize the words. He spoke as if stating a fact as simple as the sun rising in the east.

“There is one Creator. Not many. Nor should anything else in the creation be worshiped. When you understand this, many other questions become smaller.” He went on to explain the concept of tawheed, the Oneness of God, and its many applications to our lives. I began to understand that this central belief of Islam was deep and all-encompassing.

“That is enough for today,” he said eventually. “Tomorrow we continue.”

“What do you think?” Haaris asked me when the lesson was over.

“I think I have a lot to learn.” That was the best I could offer.

Jum’ah

The next day was Friday. Once again I was relegated to housework. Once the early morning tasks were done, Ma Shushu and Haaris began hitching the donkeys to the carriage. The carriage was piled high with safflowers that the farm laborers had harvested yesterday.

“Are we going to town?” I asked.

“Haaris and I are going,” Ma Shushu said. “It’s market day, and it’s Jum’ah, the main day of prayer for Muslims. We will deliver the safflowers to my sister and a few others, then attend prayer.”

“What about me?”

Ma Shushu did not meet my eyes. “Your shoulder is not healed yet. The jostling of the carriage would not be good for you.”

As they departed, all I saw was the back of the wagon and a heap of flowers. I waved, but no one saw me. The whole thing was very strange, and I couldn’t feeling there was something I wasn’t being told.

They were hardly out of sight when Lee Ayi called me to the west side of the house. She nodded to the clothes on the lines.

“Help me take these clothes down and fold them,” she said, speaking quickly. “Then take the lines down.”

“Some of the clothes are still damp,” I remarked as I took down a pair of Haaris’s trousers.

“Doesn’t matter,” Lee Ayi replied. “We’ll put them back up later.”

This made no sense to me, but I did as ordered. Lee Ayi worked fast, rushing, which was not like her at all.

* * *

Come back next week for Part 6 – A Single Step

Reader comments and constructive criticism are important to me, so please comment!

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories on this website.

Wael Abdelgawad’s novels – including Pieces of a Dream, The Repeaters and Zaid Karim Private Investigator – are available in ebook and print form on his author page at Amazon.com.

Related:

Searching for Signs of Spring: A Short Story

A Wish And A Cosmic Bird: A Play

The post Far Away [Part 5] – There Is Only Work appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

A Maccabi Tel Aviv fan gives a Nazi salute at a match in Stuttgart, Germany

A Maccabi Tel Aviv fan gives a Nazi salute at a match in Stuttgart, Germany  , Ar-Rahman, blessed me with a kind and loving father for over four decades – a gift many hundreds of people have not been privileged to have. I have seen close friends and family lose loved ones at much younger ages, and they have carried on beautifully. Why then does my heart hurt in this way? Am I an ungrateful soul? I’m not sure I know the answer to this. Can a grateful heart not feel pain? Isn’t pain also an emotion felt by the living, just as gratitude is? Just because I cry, does it mean I am not accepting of Allah’s

, Ar-Rahman, blessed me with a kind and loving father for over four decades – a gift many hundreds of people have not been privileged to have. I have seen close friends and family lose loved ones at much younger ages, and they have carried on beautifully. Why then does my heart hurt in this way? Am I an ungrateful soul? I’m not sure I know the answer to this. Can a grateful heart not feel pain? Isn’t pain also an emotion felt by the living, just as gratitude is? Just because I cry, does it mean I am not accepting of Allah’s

are my answer. You would think worship is easier for the one who loses someone dear, but no one talks about how you freeze with worship when grieving. How the heart has a yearning to connect with its Lord, but the mind remains still, lost and struggling to move. It is then that the years of holding the mus’haf close to the heart help revive it for worship. It is then, -knowing that the tears running down Muhammad’s (saw) face after losing his infant child, knowing he continued with his role as the last Prophet of Islam-, that this helps you take steps towards living life. We know about all the losses in his life, from before his birth; from the death of his father, to losing his mother, grandfather and then later his beloved wife and uncle. The seerah weighs heavily with death and grieving, but life, purpose and calling upon Allah

are my answer. You would think worship is easier for the one who loses someone dear, but no one talks about how you freeze with worship when grieving. How the heart has a yearning to connect with its Lord, but the mind remains still, lost and struggling to move. It is then that the years of holding the mus’haf close to the heart help revive it for worship. It is then, -knowing that the tears running down Muhammad’s (saw) face after losing his infant child, knowing he continued with his role as the last Prophet of Islam-, that this helps you take steps towards living life. We know about all the losses in his life, from before his birth; from the death of his father, to losing his mother, grandfather and then later his beloved wife and uncle. The seerah weighs heavily with death and grieving, but life, purpose and calling upon Allah

narrated that “The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, ‘Verily, Allah Almighty will raise the status of his righteous servant in paradise, and he will say, ‘O Lord, what is this?’ Allah will say, ‘This is (due to) your child seeking forgiveness for you.’” [

narrated that “The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, ‘Verily, Allah Almighty will raise the status of his righteous servant in paradise, and he will say, ‘O Lord, what is this?’ Allah will say, ‘This is (due to) your child seeking forgiveness for you.’” [