Aggregator

Heroic and traumatized: A volunteer paramedic’s story

Gaza out of baby formula, hundreds slaughtered at US-Israeli "aid" sites

Israel kills leading doctor, one of only two remaining cardiologists in northern Gaza.

A horrific Monday in Gaza City

Settler urging extreme violence enjoys high-level access in Brussels

“Recalling” Israel’s crimes is an empty gesture.

Turkish cartoonists arrested over satirical drawing allegedly depicting prophet Muhammad – video

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan condemned as a 'vile provocation' a cartoon in a satirical magazine that appeared to depict Prophets Mohammad and Moses, amplifying an outcry by religious conservatives after the arrest of four cartoonists. In a statement on X, LeMan said: 'The work does not refer to the Prophet Muhammad in any way'

Turkish police arrest cartoonists over drawing ‘showing prophet Muhammad’

Clashes and arrests in Turkey over magazine cartoon allegedly depicting prophet Muhammad

‘Dad, imam, God’: children living with self-declared pope in former UK orphanage

Followers of the Ahmadi Religion of Peace and Light urged to sell possessions and donate their salaries to the cause

A religious sect, whose leader claims to be the new pope and whose followers say he can make the moon disappear, is operating out of a former orphanage in Crewe, Cheshire, where at least a dozen children are being home schooled.

The Ahmadi Religion of Peace and Light (AROPL) was founded by Abdullah Hashem, a former documentary maker turned self-proclaimed “saviour of mankind” who uses YouTube and TikTok to proselytise to potential recruits.

Continue reading...Turkish police arrest cartoonists over drawing ‘showing prophet Muhammad’

Four artists held over magazine illustration alleged by critics to depict Muhammad and Moses shaking hands

The Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has condemned a cartoon in a satirical magazine as a “vile provocation” for appearing to depict the prophets Muhammad and Moses, amplifying an outcry by religious conservatives.

The cartoon, published a few days after the end of a 12-day conflict between Israel and Iran, appears to show Muhammad, Islam’s chief prophet, and Moses, one of Judaism’s most important prophets, shaking hands in the sky while missiles fly below in a wartime scene. Four cartoonists were arrested on Monday over the illustration.

Continue reading...How a new vocabulary is emerging in the genocide

Clashes and arrests in Turkey over magazine cartoon allegedly depicting prophet Muhammad

Turkey police face demonstrators after prosecutor orders arrests at LeMan magazine, whose editor-in-chief denies allegation and says image has been deliberately misinterpreted

Clashes erupted in Istanbul with police firing rubber bullets and teargas to disperse a mob on Monday after allegations that a satirical magazine had published a cartoon of the prophet Muhammad.

The clashes occurred after Istanbul’s chief prosecutor ordered the arrest of the editors at LeMan magazine on grounds it had published a cartoon that “publicly insulted religious values”.

Continue reading...Nationalism And Its Kurdish Discontents [Part II of II]: Kurds And Turkiye After Ottoman Rule

[…contd.]

As Turkiye mends its fences with a long-running Kurdish insurgency led by the Partiya Karkeren Kurdistan (PKK), the first part of this two-part series focused on Kurdish activity in and immediately after the First World War, where European powers occupied much of the former Ottoman realm only to be driven from Turkiye. This second part will focus on the first major Kurdish revolt against the modern Turkish state, the revolt of Naqshbandi preacher Mehmed Said in 1925, and its aftermath.

From Independence to SubjugationHaving fought the European powers to a standstill in the early 1920s, by the mid-1920s the Anatolian resistance was in a much stronger state and recognized as the government of Turkiye, seen as both an independent power and a useful bulwark to the Bolshevik Soviets who had taken over Russia and northern Eurasia. This gave Kemal Atatürk tremendous room to manoeuvre; rather than live up to the rhetoric of jihad and Muslim brotherhood that had marked the independence war. However, he would resort to far more limited and limiting aims of forming a Turkish nation-state.

At the 1923 Lausanne Accord, Atatürk agreed to relinquish Iraq and Syria, with the ownership of Mosul deferred till later. Muslims, Arabs, Kurds, and Turks outside Turkiye who had fought under an Islamic banner were left to their own devices. The rise of nation-states over the next decades would automatically split up the Kurds between Turkiye, Iraq, and Syria in addition to the prior frontier with Iran. An early step in the consolidation of the Turkish nation-state was the removal of Vahdettin Mehmed VI (Wahiduddin Muhammad) as sultan and then his successor, Abdulmecid (Abdul-Majeed) II, who had supported the resistance against the occupation, as caliph.

These measures, coupled with an increasingly open secularism and centralization of power around his own personage, alienated many of Atatürk’s original colleagues in the revolt against the occupation. An astonishing number of these Turkish leaders, in fact, went into opposition: they included Kazim Karabekir, Fuat Cebesoy, Ibrahim Refet, and Huseyin Rauf – who had most recently served as Atatürk’s “prime minister” in the last years of the war. Other dissidents included Nurettin Konyar, corps commanders Tayyar Egilmez, who resigned from the army to join this party, and Deli Halit (Deli Khalid)- who was bizarrely killed in a fight at parliament by Atatürk’s enforcer Ali Cetinkaya.

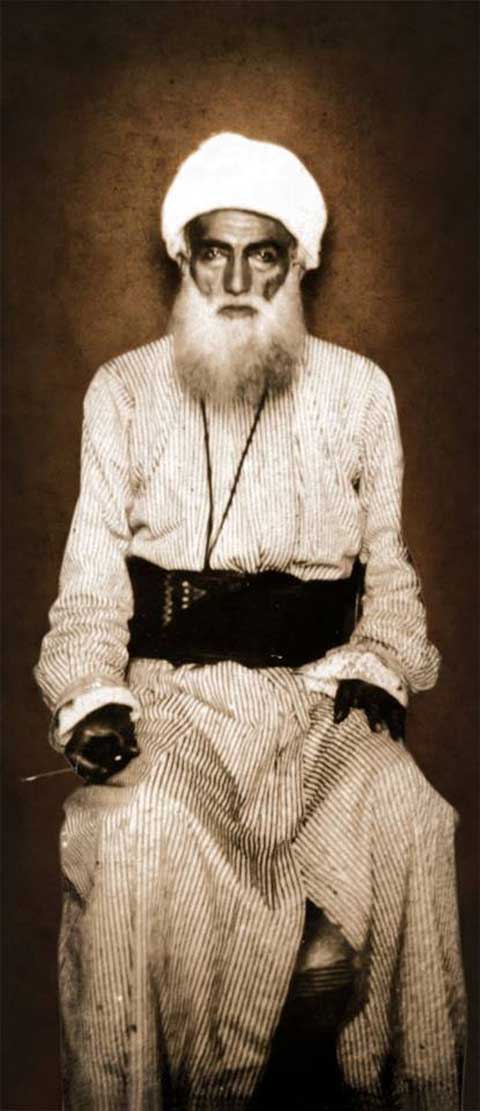

The Kurdish uprising leader Sheik Said Efendı

These were not the only quarters of discontent. Kurds had supported the new Turkish state against an Assyrian revolt, led by a Christian minority whose leaders were heavily supportive of Britain in both Iraq and Turkiye at this time, now Kurdish officers, including Halid Cibran (Khalid Jibran), from the Cibran clan, and Ihsan Nuri, planned a revolt. Halid’s brother-in-law was a revered Naqshbandi preacher, Mehmed Said (Muhammad Saeed) of Piran, who in early 1925 mounted a revolt in the region around Diyarbakir.

The revolt employed both Islamic and nationalist characteristics: Said abhorred Ataturk’s abolition of the caliphate and secularization, but echoed the nineteenth-century sheikh Ubaidullah Khalidi in his advocacy of Kurdish separatism. Said’s brother Sheikh Abdurrahim engaged an army patrol ahead of schedule, but once lit, the fire spread rapidly. Notably and unusually, not only the sheikh’s followers but also chieftains from various clans -including Begs Kadir, Mustafa, Rashid, Salih, and Yado Aga- joined the revolt. Said himself was influential among the region’s Zaza Kurds, and one major follower, Sheikh Serif (Sharif), was both a religious and clan leader. There were, of course, exceptions: Musa Beg opposed the revolt and was killed in battle. The minoritarian Alevi Kurds in Dersim also opposed the Sunni rebels, and longstanding Kurdish activists such as the Cemilpasazade family also kept their distance. Said’s attempt to contact Mahmud Ibrahim, the son of the Millan chieftain and Ottoman militia commander, went unanswered.

Nonetheless, the revolt initially captured Bingol, Elazig, and Palu to lay siege to the region’s major city Diyarbakir. The city’s tough corps commander was Hakki Mursel, a veteran of the wars with Russia who styled himself “Baku” after his battlefield experience in Azerbaijan. He held out for reinforcements against the Kurdish siege, which were soon dispatched under Ataturk’s aide, Kazim Dirik.

In the aftermath of the revolt, Atatürk cracked down hard. His loyalists, including Ali Cetinkaya and a Kurdish officer called Ali Saip, set up a show trial that accused Said of treasonous collaboration with Britain. That some other Kurdish elites had recently entertained relations with Britain might have contributed to this impression, but there is no evidence of this in Said’s case: in fact, Britain was increasingly coming to see Atatürk’s Turkiye as a bulwark against the Soviets. Just before his hanging, Said signed off to the Kurdish judge Saip with the chilling words, “I like you. But you and I shall settle our account on Judgement Day.” Saip himself would be falsely accused of attempting to assassinate Atatürk a decade later.

This marked the start of a long crackdown on Kurdish elites: also executed was Seyid Abdulkadir, who by all accounts had nothing to do with the revolt. But the crackdown extended elsewhere as well: the opposition led by Kazim Karabekir was implausibly accused of having conspired in the revolt, and their party was immediately banned. A year later, when Atatürk survived an attempt on his life, Kazim and the other dissident leaders were systematically hounded out of public life.

Said’s revolt was a watershed moment not only for Kurds in Turkiye but for Turkiye itself: it marked the start of a progressive concentration of power around a foreign concept of the nation-state. Though he abjured the extraterritorial ambitions of Turkish nationalists, Atatürk shared the common nationalist idea that heterogeneity was a weakness and sought to fashion a new, modern type of Turkish citizen: the Kurds were simply treated as backward specimens of “mountain Turk” who would have to be “civilized” by force. This provoked revolt, notably led by Ihsan Nuri at Agridag, which was crushed with greater brutality in the early 1930s. Led by such hardline Kemalists as Kazim Dirik, the regime began a policy of social engineering that, while not restricted to Kurds, was particularly violent in their case. Repression, including against as basic a fact of life as the Kurdish language, was ferocious; in the late 1930s, the Dersim Alevis, who had opposed the 1925 revolt, were themselves brutally crushed.

A Long Shadow

Kazim Karabekir and Kemal Ataturk

It is often claimed that Kurds are the world’s largest nation without a state; this, however, internalizes the same nationalist logic that produced nation-states in the early twentieth century, that each ethnic group must have a distinct state. More to the point is the overwhelmingly harmful impact that nationalist homogenization and government centralism throughout the region have had on Kurds, who have been split between four states in Turkiye, Iraq, Syria, and Iran–respectively known as Bakur (North Kurdistan), Bashur (South Kurdistan), Rojava (West Kurdistan), and Rojhilat (East Kurdistan).

Experiences often varied: in Syria and Iraq, the atmosphere grew increasingly fraught with the emergence of Arab nationalism led by rival wings of the Baath party. Iraq, originally been relatively open, but where Barzani leader Mala Mustafa remained one of several charismatic rebels, and Iran in the 1970s backed one another’s Kurdish opposition as the two neighbours entered a major war that lasted through the 1980s. A particularly brutal assault by Iraq’s Baath regime on its Kurds ensured that when an opportunity came in the 1990s, the Iraqi Kurds set up a practical American protectorate in Bashur, a duopoly led by the feuding Barzani and Talabani cliques. Though they maintained links with Kurds abroad, they also had complicated relations with the governments that other Kurdish activists opposed.

Though Turkish politics opened up after the Second World War, the deep state maintained a close watch on politics and jealously sought to guard Atatürk’s legacy. Crackdowns on Kurds resumed in the 1980s when Abdullah Ocalan, a Stalinist activist who formed a personality cult, led a new revolt that differed in style from previous Kurdish revolts but shared their aim of throwing off rule by a military-led Turkish government, and worked closely with the Syrian regime of Hafiz Assad. Ankara eventually persuaded Assad to relinquish Ocalan, who was captured in 1999 even as his organization was repeatedly pursued into Bashur. Though many Turkish officials, including Prime Minister Turgut Ozal, were themselves Kurds, they could not shake a solidly uncompromising military and bureaucratic establishment that again domestically reared its head in the late 1990s, when it cracked down on Islamic practice with the close support of the United States and Israel.

As a consequence, Islamic activists in Turkiye came to see this ideological autocracy as a shared enemy with the opposition Kurds. The Islamic-leaning AK party that came to power in 2002 repeatedly sought to bury the hatchet with Kurdish insurgents, meanwhile taming the military. This process stuttered in the mid-2010s when American support for the Karkeran’s Syrian wing emboldened the main organization in Bakur to return to insurgency. That provoked yet more cross-border Turkish incursions, this time into northern Syria (or Rojava, West Kurdistan). Only a decade later, with Washington losing interest in the Syrian misadventure and a pro-Turkish Islamist government in Damascus, did negotiations resume, with the ethnically Kurdish Turkish foreign minister Hakan Fidan playing a major role.

Importantly, it was Turkish nationalist leader Devlet Bahceli, whose party has traditionally abhorred concessions of Kurdish rights, who opened up negotiations with Ocalan. The Turkish parliament proved similarly receptive, and in May 2025, Ocalan announced the disbandment of the Karkeran in return for cultural rights. It remains to be seen whether this will play out as negotiated, but it marks a rare opportunity to end a century of injury for the Kurds of Turkiye and take a more organic approach to Kurdish rights in the region.

Related:

– Western Europe and the Ottoman Empire: Trade Across an Inverted Imperial Divide – MuslimMatters.org

– Part I | The Decline of the Ottoman Empire – MuslimMatters.org

The post Nationalism And Its Kurdish Discontents [Part II of II]: Kurds And Turkiye After Ottoman Rule appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

When will I graduate high school in Gaza?

Nationalism And Its Kurdish Discontents [Part I of II]: Kurds In An Ottoman Dusk

This spring, Turkiye’s AK government, led by Tayyip Erdogan, secured what promises to be a momentous agreement with the longstanding Kurdish insurgent group, the Parti Karkeran Kurdistan (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) led by Abdullah Ocalan, which has waged an insurgency against the Turkish state for the better part of four decades. This comes a hundred years since the first Kurdish revolt against the Turkish Republic, the 1925 revolt led by the Naqshbandi sheikh Mehmed Said against the republic’s founder, Kemal Atatürk. This first of two articles on the Kurds in Turkiye will examine the background of Kurdish activism during the final years of the Ottoman sultanate.

BackgroundAs a multiethnic Islamic sultanate, Ottoman rule from Istanbul was systematically undermined by the nineteenth-century emergence of nationalism, which both undercut Islamic universalism and provoked unrest among the sultanate’s Christian minorities, often with support from rival European powers such as Britain and Russia. As a European import, nationalism had a limited appeal until Istanbul’s own attempts at centralizing administrative reforms, which often met a sharp backlash outside the corridors of power. As fellow Muslims who had enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy under traditional leaders such as chieftains and preachers, few Kurds welcomed Ottoman centralism and a number of major families, notably the Bedirkhans (Badr Khans) of Bohtan, resisted these measures, as well as sociopolitical upheaval caused in the borderlands with Russia and Qajar-ruled Persia. In 1880-81, the Nehri Naqshbandi preacher Ubaidullah Khalidi b. Taha led a major attack on Iran, and only relented under the pressure of Ottoman sultan Abdulhamid II before briefly challenging the Ottomans in turn.

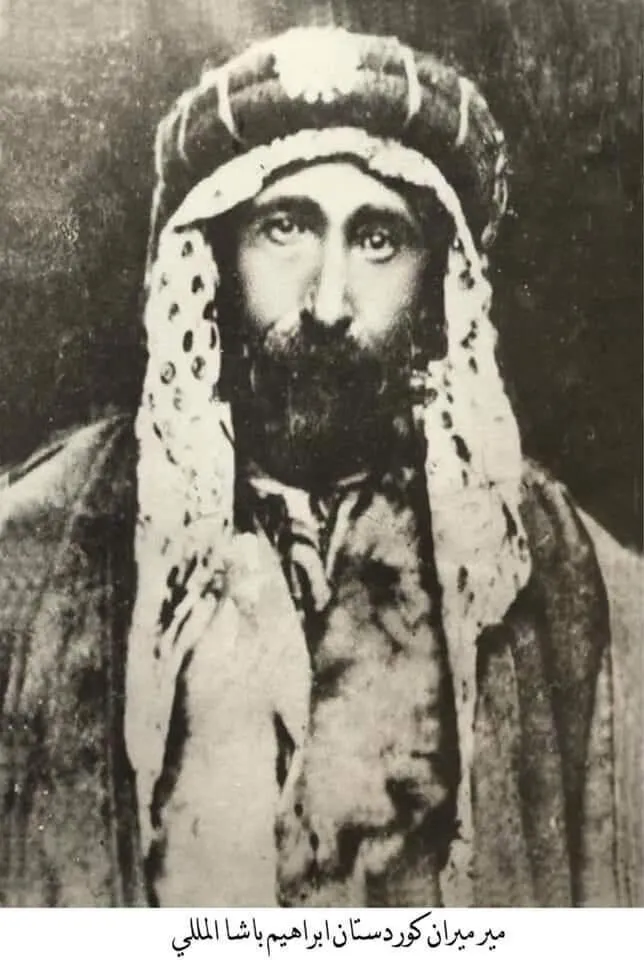

Ubaidullah’s dissatisfaction with Ottoman and Qajar rule, as well as his insistence on an autonomous if not independent Kurdish frontier, has made him renowned as a proto-nationalist. He adopted a stance that would be echoed in many future Kurdish leaders, including his son Seyid Abdulkadir: official loyalty to the government, but parallel negotiations with foreign powers with a view to securing autonomy from centralism. In fact, the vast majority of Ottoman Kurds remained loyal to the government, and Abdulhamid increasingly armed them under the command of Millan chieftain Ibrahim Milli to fight Armenian nationalists backed by Russia during a bloody, undeclared war at the turn of the century. Stressing his title as caliph, Abdulhamid was nonetheless widely resented by a wide number of people, particularly the intelligentsia, by this point: his secretive, wary rule during a period of decline was increasingly resented and when he was ousted in the so-called Young Turk coup of 1908, traditional Kurdish leaders were among the few who rallied to his cause. Millan chieftain Ibrahim in Syria and the Barzinjis Saeed and his son Mahmoud in Iraq launched brief and unsuccessful revolts against the new regime.

HomogenizationThe Young Turk coup, which brought together a mishmash of ideological and political trends united only by their desire for change, promised a more representative government, but in fact, proved far more repressive than its predecessors. Though a number of the Young Turks were Kurds, and though such Kurdish notables as Seyid Abdulkadir were given senior positions, in fact power soon came to rest with a militaristic clique that, in the “civilized” fashion of the day, viewed Ottoman heterogeneity as a potential weakness and increasingly sought not only centralizing but also culturally homogenizing practices, with the particular promotion of Turkish identity often at the expense of other identities.

Notable Kurdish families and leaders, including the Bedirkhans, Babans, and the Cemilpasazades (Jamil Pashazadas), were forced to operate underground. Others, such as the Barzanis, who had a record of rather heterodox religious activity but enjoyed a widespread following in what is now northern Iraq, briefly rebelled. Several Kurdish clans broke off their relations with the Ottomans; when, during the Balkan War of 1912-13, Istanbul came under threat, one chieftain, Abdulkadir Dirai of the Karakecili, expected that the Ottomans would fall and rebelled, only to be imprisoned once they survived. Other Kurdish clans remained loyal to the sultanate and were often employed against their local rivals.

Ibrahim Milli [PC: haberercis.com.tr]

Often, government responses were coloured by the assessment of individual officials who were not themselves necessarily Turks: for instance, Mehmed Fazil (Muhammad Fadil) and Suleiman Nazif, two of the firmest opponents of the Kurdish rebels in Iraq, were respectively Caucasian and Kurdish. For their part, some of the Kurdish intermediate class -which had historically been autonomous links between their communities and the Ottoman sultanate- were increasingly equivocal, doubting the feasibility of the Ottoman state and prepared to break away should it fall to foreign intervention. It was in this context that an explicitly nationalist idea of Kurdishness came about.Throughout the devastating First World War that followed, Kurds fought in huge numbers for the Ottoman state: as many as three hundred thousand Kurds lost their lives in the Ottoman cause, and major units in the eastern frontline against Russia were largely Kurdish. The war saw communal displacement and upheaval on an unprecedented level, and not simply by the Ottomans’ enemies: though Russian-backed Armenian nationalists had been extremely brutal against Muslim civilians, the Ottoman state responded with a wholesale assault on the Armenian populace at large, which was massacred and systematically displaced. This was to date the worst assault of any Muslim government against a dhimmi minority; it was also a precursor to ideas of homogenization that would emerge after the war.

During the war, a handful of Kurdish notables, including Abdulkadir’s nephew Seyid Taha of Nehri and some of the Bedirkhans, openly colluded with Russia as it briefly captured the borderland. This availed them little as Russia soon collapsed, but was less momentous than the role of Arab counterparts -again, against the vast majority of loyalist Arabs- who helped Britain advance in Arabia and the Levant. Eventually, the Ottomans were forced to sue for peace in the autumn of 1918, whereupon their remaining opponents -France, Britain, and Greece, with a smattering of Italian and Armenian nationalist forces- occupied Istanbul and the surrounding countryside. The recently installed Ottoman sultan, Vahdettin Mehmed VI, sought to cut his losses, purge the Young Turks, and enter a disadvantageous peace with the victors: he hoped that a shared dislike of the Young Turks, who had brought the sultanate to ruin, would enable the European victors to view him with sympathy, but they instead aimed to split the Ottoman heartland between them. In this context, Kurdish nationalists, led by an Ottoman Kurdish general called Mehmed Serif (Muhammad Sharif), also sought the establishment of an independent Kurdistan.

Resistance and CollaborationBy contrast, other Kurds, as well as Turks and Arabs, fought this occupation of Muslim territory. In Anatolia’s heartland, they were led by a number of renegade Ottoman generals: Kemal Atatürk, Kazim Karabekir, Ibrahim Refet (Bele), Fuat Cebesoy, and Vahdettin’s former negotiator, Huseyin Rauf (Orbay). Although the palace treated them as rebels, they insisted that they were liberating the sultan from foreign subjugation, and their argument was given strength by the European powers’ uncompromising stance toward Istanbul. They employed Islamic arguments of jihad that intermixed with already existing resistance elsewhere, both in Anatolia as well as Iraq and Syria, and these at least originally united many Kurds with Arabs and Turks.

Though the sultan and Atatürk reached an uneasy agreement by the end of 1919, in spring 1920 Britain sabotaged this with a full-scale crackdown in Istanbul. This forced the remaining parliament to flee to Ankara, where Atatürk set up a “shadow government”. The last humiliation for the sultanate came in the Sèvres Accord: though Vahdettin had hoped that he could salvage a good deal through cooperation with the occupation, in fact, the European powers decided to split up his lands and thus lent credence to the Ankara-based parliament’s call for a jihad. Although the Accord rewarded Mehmed Serif’s lobbying with a vague reference to Kurdistan, in actual fact this came after a year of fierce fighting between Britain and large parts of the Ottoman Kurdish population.

Kurdish participants in resistance included several Kurdish chieftains: Ali Bati of the Haverkan clan, Abdurrahman Aga of the Shernakhlis, and Ramadan Aga of the Salahan. Similarly, Karakecili chieftain Abdulkadir Dirai and Millan chieftain Ibrahim’s son Mahmud were released from prison to lead Kurdish forces. But the political uncertainty and ambiguous jurisdiction of the period, and suspicion and rivalries among the participants often clouded events. For instance, when Bati captured Nusaibin in May 1919, the army led by Kenan Dalbasar wrongly suspected him of French-backed subversion and drove him out, where he was killed. Similarly, when Istanbul sent a governor, Ali Galip, to arrest Atatürk that autumn, he was accused of being in league with French-backed Kurdish secessionists, causing the palace huge embarrassment. Finally, in early 1921, a particularly ruthless Turkish general, Nurettin Konyar, uprooted a largely Alevi Kurdish revolt by the Kocgiri clan in eastern Anatolia, with a ferocity that alarmed even his colleagues in the resistance. This revolt had demonstrable links to the British occupation and to Serif’s secessionists, thus cementing a suspicion of Kurdish agitation that was to resurface again.

In fact, Kurdish collaboration with Britain was the exception to the rule. Resistance was especially fierce in British-occupied Iraq, in whose north Ottoman veterans such as the Young Turks’ former defence minister Ismail Enver encouraged Kurdish revolt among historically rivalled clans such as the Zebaris, the Barzanis, and the Surchis. Participants included Mala Mustafa of Barzan, Karim Fattah of Hamawand, Faris Agha of Zebar, Mahmoud Dizli of Hawraman, Nuri Bawil of the Surchis, Abbas Mahmoud of Pizhdar, and Mahmoud Barzinji. Their local rivals backed Britain, along with opportunists such as Seyid Taha as well as chieftain Ismail Simko of the Shikak clan, a marauding freebooter on the Turco-Persian borderland who had once fought for the Ottomans but often changed sides.

Sheikh Mahmud Barzanji (Kurdish: Mahmud Barzinji (1878 – October 9, 1956) was the leader of a series of Kurdish uprisings against the British Mandate of Iraq. He was sheikh of a Qadiriyah Sufi family of the Barzanji clan from the city of Sulaymaniyah, which is now in Iraqi Kurdistan. He was styled King of Kurdistan during several of these uprisings. [PC: Alamy Stock Photo]

In summer 1921 Britain, at their wits’ end and by now reconciled to the inevitability of a Turkish victory in Anatolia, decided to cut their losses and set up a nominally independent Iraqi state under Faisal I bin Husain, who had supported them against the Ottomans in Arabia but been deprived of a kingdom when France had conquered Syria from him in 1920. The new state would be largely comprised of Faisal’s followers as well as parts of the largely Arab Iraqi intelligentsia from Ottoman rule: though Ataturk was not averse to letting go of Baghdad, the Turks and British both laid claim to Mosul, which was believed to contain vast deposits of oil.In summer 1922, Ankara dispatched Sefik Ozdemir (Shafiq Ozdamir), the descendant of a notable Mamluk family who had most recently fought France and, during the World War, encouraged a shared Muslim opposition to the European foe. Far more than other Turkish officers, Sefik won the trust of Kurdish clansmen, supporting Karim and Abbas in battle against the British occupation. Unable to trust the weak Taha or the adventuresome Simko, Britain turned instead to Mahmoud Barzinji, who promised to repel the resistance if they let him rule Sulaimania. Once installed there, however, he made contact with Sefik and joined the revolt to announce himself shah of Kurdistan.

It was not until 1923 that this joint Turkish-Kurdish resistance was defeated. Though Mahmoud Barzinji was expelled from Sulaimania, British rule in the Kurdish region was extremely tenuous, and he was able to return repeatedly over the next few years. In order to beat him and other Iraqi opponents, Britain relied on massive aerial bombardment, a novel technology a the time that wrought havoc on the Kurdish countryside in a process that would be repeated by one government or another against Kurdish rebels over the next century.

[…to be contd.]

Related:

– The Role Of Kurds In The Dissemination Of Islamic Knowledge In The Malay Archipelago

– Calamity In Kashgar [Part I]: The 1931-34 Muslim Revolt And The Fall Of East Turkistan

The post Nationalism And Its Kurdish Discontents [Part I of II]: Kurds In An Ottoman Dusk appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Moonshot [Part 10] – The Marco Polo

Cryptocurrency is Deek’s last chance to succeed in life, and he will not stop, no matter what.

Previous Chapters: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

“Those with gold in their pockets gather, but in the hush of their greed they learn that voices of love grow faint. So they end up dining alone—no one dares place real trust upon them.”

— Chinua Achebe, A Man of the People

TravelizeWhen Zaid ended his salat and stood, Deek repeated, “I don’t know what to do next. I’m not ready to go back to Rania. She needs to show me something. I need a sign from her.”

“Why don’t you show her something? What signs have you given her?”

These interrogatives threatened Deek’s mind with turmoil. Instinctively he resisted, pushing the questions away.

When he did not answer, Zaid said, “Why don’t you check into a hotel for a few days?”

“I’m not liquid yet. There’s cash coming, but at the moment I’m down to a hundred and fifty bucks.”

“Didn’t you just offer me a million dollars?”

“Yeah but in crypto. It’s in a crypto wallet. Not cash.”

“Yeah but in crypto. It’s in a crypto wallet. Not cash.”

“Aren’t there any hotels that accept crypto?”

Deek stared at the lean, scarred detective for a moment, then slapped his own forehead. “Of course! Travelize! It’s a crypto company that lets you book hotels or flights with crypto. Man, I actually own Travelize tokens. What a dummy I am.”

His phone charge was down to 10%, but he did a quick search. There were several hotels in Fresno that worked with Travelize, mostly Motel Sixes, Hampton Inns and Comfort Inns, but there was also the Ramada, a Marriott, and – boom! – the Marco Polo, a high-end boutique hotel that had just opened in north Fresno two years ago. In dollars the Venetian Suite was $1,550 a night, but Travelize accepted a wide range of cryptos. Deek booked a room for a week. With the wealth he now possessed, fifteen hundred dollars a night was nothing.

Allah, Deen, FamilyZaid told him that the Namer had said he could keep the flannel pajamas. Somehow this made Deek happy. This place was special. He was only sorry he hadn’t met the old woman. Or at least he assumed she was old, though now that he thought about it he had no idea.

As the two of them extinguished the candles and exited the house together, Deek paused. “I can’t believe we’re leaving it unlocked. It’s nuts.”

Zaid said nothing, but looked troubled.

“You’re going to tell me again,” Deek said, “that I should go back to my family.”

Zaid waved this off. “It’s up to you. But really, what else is there? Allah, deen, family, doing work you love, and doing good in the world. And by the way, if you really want to give away a million dollars, give it to some of the charities operating in Gaza. The situation there is beyond dire. It’s unspeakable. And you purify your wealth in the process.”

Deek grunted. That was a good idea.

“I was thinking,” Deek said, “of changing my name to Asad.”

Zaid raised his eyebrows. “Changing your name is a big thing.”

“Not my family name. Just my first name. And not even legally, just in daily use.”

“So you want me to start calling you Asad?”

“No… I’m not sure. I’ll let you know.”

They parted ways with a handshake.

The Marco PoloThe Marco Polo Hotel was stunning. The four-story hotel had only 20 spacious suites – five per floor – with each modeled on a theme based on Marco Polo’s travels. The lobby was furnished with elegant velvet-upholstered armchairs, featuring carved wooden frames and cushions in shades of aquamarine or deep wine-red. Live olive trees in planters, stretching up toward the high ceiling, while Murano glass sculptures of seabirds caught the sunlight streaming in through the windows and refracted it in every direction.

On one side of the lobby, a full sized vintage gondola had been installed as a reading nook, with velvet upholstery inside. A young woman in a flowing yellow dress sat inside it, looking at her phone, while a tall, bald man in a suit – presumably her father – sat nearby, reading the Los Angeles Times.

Deek checked into the Venetian Suite, on the fourth floor. For a moment he simply stood in the doorway, the keycard warm in his hand, as his eyes swept across the room. Everything glowed in sun-washed gold—cream-colored drapes drawn open to tall windows, a vaulted ceiling painted with soft clouds, and polished marble floor that caught the light like water. The silence was broken only by the delicate sound of trickling water.

In the center of the room, rising from a round base of veined Carrara marble, stood a fountain. White and flawless, carved with meticulous detail. Three lion heads—fierce, proud, unmistakably Venetian—spouted arcing streams of water into a shallow basin. It was beautiful. And utterly absurd.

He walked a slow circle around it, unable to stop himself from staring. The lions’ eyes were narrowed in eternal judgment. He felt like they were staring at him.

He lowered himself onto the edge of the bed. The mattress barely shifted beneath his weight, and the silken sheets were so smooth they felt unreal beneath his fingers.

DislocationHe knew it wasn’t rational. He’d paid in full. The suite was his for the week. But payment wasn’t the same as permission.

He looked around again—at the fountain, the chandelier that sparkled like crystal rain, the velvet chairs, and the desk that looked like it had been stolen from a Renaissance library—and the ache returned. A soft, hollow pang in his chest. Not quite grief. Not quite fear. Just… dislocation.

He remembered the couch he’d grown up with—brown corduroy, cracked at the seams, with stuffing poking out the arm. It smelled like frying onions, baby powder, and dust. The floor in that apartment had creaked. The heater had hissed. The entire family had shared one bathroom, and he and Lubna had shared a bedroom, sleeping in a bunk bed. Deek on the bottom, Lubna on top. But it had been home.

He stood again and wandered to the writing desk. It was inlaid with mother-of-pearl, the drawers lined in blue velvet. Inside one drawer, he found thick, cream-colored paper and a pen that looked like a relic from some old Venetian council chamber. He didn’t know what to write. He didn’t even know how to sit in a chair like that.

The minibar was stocked with bottles he couldn’t pronounce. The music panel on the wall offered a playlist labeled Venezia Notte. He didn’t touch it.

The First to Pray His father often used to tell him that any part of the earth on which a man prayed would speak for him on Yawm Al-Qiyamah. Deek wondered if anyone had ever prayed in this room. If not, he could be the first.

His father often used to tell him that any part of the earth on which a man prayed would speak for him on Yawm Al-Qiyamah. Deek wondered if anyone had ever prayed in this room. If not, he could be the first.

He wandered into the bathroom, which looked like a room in a palace, with a cream-colored marble floor polished to a mirror shine, a massive arched mirror, a freestanding octagonal bathtub set into a niche decorated with Venetian mosaic tilework, and cabinets that appeared to be cherry wood or walnut. Plush white slippers and a thick white robe rested on a wooden bench near the tub. Deek picked up the robe, and his eyes widened. It was monogrammed DS – his own initials!

It was too much. It was not the luxury that overwhelmed him, but the strangeness of it. With shaking hands he performed wudu’, then used a towel as a musalla, praying ‘Ishaa in the sitting room. It calmed him, and reminded him that some things did not change. Allah was still Allah, and always would be. He, Deek, was a servant of Allah, and – by the grace and will of Allah – always would be.

A Long Way From the Moon WalkHe turned off the lights, one by one, but couldn’t figure out the chandelier. There was no visible switch. So he changed into the bathrobe and lay down on the bed in the illuminated room, the soft gurgling of the lion fountain filling the silence.

He thought about Rania, and wondered what she was doing at that moment. Probably quilting. Sewing quilts was her favorite hobby. Every friend she’d ever had probably owned at least one or two, given as gifts on birthdays, anniversaries and baby showers. She said that the hour she spent quilting before bedtime relaxed her and helped her sleep.

This was a long way from the Moon Walk Motel and its sagging mattress. Somehow he’d been more comfortable at the Moon Walk. Until he was kidnapped, anyway. He hadn’t thought much about the kidnapping. The killing of those men was like a movie scene in his mind. Grand and cinematic – cue the music. He felt no guilt or remorse. Those thugs had gotten what they deserved. He certainly remembered the pain of the beating the men had given him, and the terror he’d felt, yet it was remote now.

He had money now. Enough to stay here, to buy security and silence, along with cool air, bottled water and simulated serenity. But no one had told him what to do once he got here.

Fair Weather Friends The next morning, the suite smelled like sunlight and saffron. Deek sat on the edge of the silk-draped bed in a plush monogrammed robe, a room service tray spread out across the coffee table beside him. His fingers, still stiff with sleep, tore a buttery croissant in half. The flake-crackle of crust and the warm scent of honeyed pastry filled the air. He dipped it into a demitasse of strong espresso, the bitter steam rising to his face, then chewed slowly, listening to the low sound of the marble fountain gurgling like a small spring.

The next morning, the suite smelled like sunlight and saffron. Deek sat on the edge of the silk-draped bed in a plush monogrammed robe, a room service tray spread out across the coffee table beside him. His fingers, still stiff with sleep, tore a buttery croissant in half. The flake-crackle of crust and the warm scent of honeyed pastry filled the air. He dipped it into a demitasse of strong espresso, the bitter steam rising to his face, then chewed slowly, listening to the low sound of the marble fountain gurgling like a small spring.

The suite was silent, padded in velvet and marble, but Deek’s mind was restless. He’d slept too well, too deep—waking with a vague disorientation, as if he’d surfaced from under warm water only to realize he didn’t know the shore.

He unlocked his phone, almost absently, and saw the red dot: 9 new voicemails. He frowned. There had been only three yesterday. And he didn’t recognize any of the numbers except that of Faraz, the bright, enthusiastic facilities manager at Masjid Madinah. Faraz, a 35-ish Bangladeshi American who treated the English language like a rapper’s hummed tune, was into crypto too. The two of them had bounced ideas and strategies off each other for years. Many times Faraz had invited him back to the masjid kitchen and brewed some coffee for the two of them as they talked about cryptocurrency developments.

He listened to Faraz’s message first, whose voice was bright and animated:

“Yo, Deek! Brooo! SubhanAllah man, I seen it! Don’t even try to act low-key, I been tracking you on Pump—your wallet straight up exploded. You always had the eye, wallahi. You flipped that New York Killa like a champ, bro, three hundred to four milli? I told my cousin, I said, ‘This guy? He’s him. He’s him.’ Look, we gotta catch up, man. I’m talkin’ coffee, donuts and graphs. Lotta brothers tryna connect with you now—real talk. You the main event. Hit me back.”

Deek blinked, mid-sip. The espresso turned to charcoal in his mouth.

How the hell does he know?

Then he remembered. Pump fun usernames were tied to wallets. And Faraz traded too—they’d swapped strategies back in the day, even co-invested in a few doomed meme coins. If Faraz had his wallet address, he could’ve been watching the whole time.

Everything on-chain is visible. That’s the point. No one knows your identity, but they can see exactly what’s in your wallet. And if they know your wallet address, they know what you’re holding.

He put down the tiny cup and leaned back, thumb hovering over the next voicemail.

A young voice. Pakistani accent.

“Assalaamu alaykum, brother Deek. This is Anas—I work for Sierra Engineering? We met at Jummah once. Anyway, I’d love to grab coffee if you’re free.”

Delete.

Next. A slow, oiled voice. Palestinian maybe.

“Brother Deek! This is Nabeel. You remember my dealership—Royal Auto, right off Shaw? Come by anytime, let’s break bread. I’ll even give you a deal on an S-Class.”

Delete.

Six more. All variations on the theme: Salaam, coffee, lunch, maybe dinner. Some tried to play it casual. Others sounded like they were calling a long-lost cousin. One even said, “We should hang out again,” though Deek couldn’t remember ever hanging out with the guy in the first place.

He stared at the screen, thumb hovering.

They wouldn’t have said two words to me a month ago. Now I’m a millionaire on-chain, and suddenly I’m a long-lost brother.

A curl of bitterness tightened behind his ribs. He was sitting in a palace, his breakfast likely costing more than his old car payment, and yet it all felt… exposed. He hadn’t asked for attention. He’d bought New York Killa on a gut feeling and sheer desperation. He didn’t want to be anyone’s poster boy or networking opportunity.

He deleted the remaining messages, one by one. The tap-tap-tap of his thumb sounded final, almost satisfying.

Then he opened a message to Faraz:

Appreciate the congratulations. But I didn’t want people knowing. Disappointed you shared that without asking. Would’ve expected better from you.”

He stared at it for a moment, then hit send.

The phone felt heavier in his hand. He set it down beside the untouched slice of melon and leaned back, listening to the lazy fountain and the faint creak of sunlight through the heavy drapes.

All this marble. All this gold. And still, the old feeling settled back into his chest like it never left. He was alone. Still stuck in the closet, choking on his own sweat and isolation. Only the view was better.

Charts on Cracked ScreensA text reply came from Faraz:

Astagfirullah, wallahi I’m sorry bro. I didn’t mean to put you on blast. I just got hyped. You know me, I get loud when I’m proud. You been grindin’ since forever. I won’t say a word to nobody else. Just happy for you, akhi.

Deek sighed. He knew Faraz meant well. That brother had been riding shotgun in the struggle—back when they were both scraping coins together, watching charts on cracked screens, chasing the same wild trades and sharing bad coffee in the masjid kitchen.

He remembered Faraz’s smile as he poured Turkish brew from a dented kettle, steam rising, the aroma cutting through the masjid’s dusty storage smell. The way his eyes lit up when he said, “If you ever catch a true moonshot, bro? You better remember who made your coffee when no one else believed in you.”

Deek smiled in spite of himself.

He typed, slowly:

It’s alright. Just lay low with it, yeah? And we’ll link up soon, inshaAllah.

Steak and Italian ShoesHe went out that day and bought two flat screen computer monitors with the $5k he’d transferred to his bank account. He ate at the hotel restaurant, which served high-end American food like Angus steak, wild-caught salmon and gourmet burgers. Deek still had no desire for junk food of any kind, and found himself eating healthy, balanced meals. He sat in a corner of the restaurant, eating alone, reading crypto news on his phone. More voicemails came in. He deleted them all without listening.

The hotel had its own clothing store, providing tailored suits and Italian shoes. Deek bought three outfits. All of this was billed to his room and paid for with crypto.

He set up his workplace and resumed trading. The Namer’s potion continued to do its magic. His body had nearly completely healed from its injuries, and he felt energetic and strong. His mind was sharp and clear as well, while his emotions were curiously dulled. He found himself making the best crypto trading decisions of his life.

A few of the speculative AI tokens he’d bought recently had crashed to almost zero, but two were up considerably, and one of them had done a x30, netting him more than ten million dollars. He sold 90% of it and parked half the money in USDC stablecoins for now. It was always good to have a stablecoin war chest in case of mid-cycle corrections. The other half he dropped into some very low cap – less than $500K – AI related tokens, as well as a meme coin and a new NFT trading site. By the end of the day, he was up another ten million, bringing his net worth to over one hundred million dollars.

The Namer’s PotionThe spacious, air conditioned hotel office was a far cry from the cramped and stifling closet he’d worked in for five years, and he found himself resenting Rania for putting him through that, for hiding him away like some deformed and crazy uncle.

The Namer’s potion was still working inside him, though. While in the past this resentment might have simmered in his gut, growing worse with each day, now he found himself able to dismiss it. He reminded himself that she’d worked and supported the entire family for five solid years while he lost money, throwing it down the drain of one bad investment after another.

Several times that day, Rania sent texts saying, “Why don’t you respond to my messages?” Deek replied, “Busy at the moment. We will talk soon.”

Several times that day, Rania sent texts saying, “Why don’t you respond to my messages?” Deek replied, “Busy at the moment. We will talk soon.”

He missed Rania and loved her. They’d been through so much together. He remembered when they had first married, when they lived in that cramped little apartment on Millbrook Avenue, with the threadbare carpet, and the air conditioner that kept breaking down in the middle of summer, leaving them sweating like horses, cranky, and exhausted. Whenever the heat became unbearable they walked hand in hand to Einstein Park on Dakota, where they ate lunch outdoors in the shade of an elm tree. They fought, but they loved each other, and forgave everything.

But she’d said he was an anchor around her neck. The words haunted him. Every time he thought about going back to her the words rang in his head. Anchor around my neck. That wasn’t how you spoke about someone you loved.

Sitting there in that palatial suite, as comfortable and cool as a head of broccoli, Deek hated himself and his own clenched, self-centered, unforgiving heart. The feeling was so strong that it broke through the Namer’s potion, making him wince and rub his face in shame. Why was he like this? Why did he hold onto grudges like a man in quicksand holding onto a rope, when in reality the rope was on fire? Why was he so unbearably proud? Why couldn’t he be the bigger person, the better person? Why was he now richer than he ever dreamed, yet all alone?

That night, Deek woke up at two in the morning and ordered a mac n’ cheese from room service, because he could – the kitchen was open 24 hours – and because Latifah. If she could do it, so could he. They brought it to him in a metal goblet, as if he were an earl or a duke, but he wasn’t, he was a count – the Count of Crypto, counting his crypto. He sat on the floor with his back against the wall, half asleep, eating the creamy, tangy concoction with a long metal spoon. His legs were crossed and his chin lowered in the posture of a mendicant, assuming a position of humility before the passing crowds, begging for whatever filthy coins they might drop into his goblet.

Where was everyone? Where was Rania, Sanaya, Amira, Lubna, Zaid, Marco, Rabiah Al-Adawiyyah, and Queen Latifah? All the people who loved him, and he loved them?

He never finished the mac n’ cheese. His chin dropped to his chest, his eyes closed, and the spoon slipped from his hand, clattering onto the marble floor. If a crow had peered through the window, it might have thought he was dead, or awaiting death’s arrival. It might have called out to him. Or it might have simply watched and waited.

***

[Part 11 will be published next week inshaAllah]

Reader comments and constructive criticism are important to me, so please comment!

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories on this website.

Wael Abdelgawad’s novels – including Pieces of a Dream, The Repeaters and Zaid Karim Private Investigator – are available in ebook and print form on his author page at Amazon.com.

Related:

The post Moonshot [Part 10] – The Marco Polo appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Madina: The Enlightened City review – a fact-filled tour of Islam’s second holiest city

Despite the dryly informational tone, this documentary guide to the prophet Muhammad’s final resting place features breathtaking footage

Here is a tour guide of the Islamic holy city best known in the UK as Medina in Saudi Arabia, a major destination for religious tourism, second only to Mecca. It is home to Islam’s first mosque, and the prophet Muhammad’s final resting place. For anyone planning a visit, this documentary about the city’s sacred sites is well worth a watch. Non-Muslims may find themselves reaching for their phones to look up terms and historical events.

There is an antiquated, mildly academic feel to the voiceover, like a BBC documentary from the 1970s. It begins with a brief overview of the prophet’s migration from Mecca to Medina in 622AD, marking the start of the Islamic calendar. In the present day, the faces of pilgrims are a window into the significance of this spiritual journey for those with faith – but none are actually interviewed.

Continue reading...Zohran Mamdani won by being himself – and his victory has revealed the Islamophobic ugliness of others | Nesrine Malik

The vicious reaction to his New York mayoral success tells us this: the establishment will not countenance mainstream voters making common cause with Muslims

Zohran Mamdani’s stunning win in New York’s mayoral primary has been a tale of two cities, and two Americas. In one, a young man with hopeful, progressive politics went up against the decaying gods of the establishment, with their giant funding and networks and endorsements from Democratic scions, and won. In another, in an appalling paroxysm of racism and Islamophobia, a Muslim antisemite has taken over the most important city in the US, with an aim to impose some socialist/Islamist regime. Like effluent, pungent and smearing, anti-Muslim hate spread unchecked and unchallenged after Mamdani’s win. It takes a lot from the US to shock these days, but Mamdani has managed to stir, or expose, an obscene degree of mainstreamed prejudice.

Politicians, public figures, members of Donald Trump’s administration and the cesspit of social media clout-chasers all combined to produce what can only be described as a collective self-induced hallucination; an image of a burqa swathed over the Statue of Liberty; the White House deputy chief of staff, Stephen Miller, stating that Mamdani’s win is what happens when a country fails to control immigration. Republican congressman Andy Ogles has decided to call Mamdani “little muhammad” and is petitioning to have him denaturalised and deported. He has been called a “Hamas terrorist sympathiser”, and a “jihadist terrorist”.

Continue reading...Will "terrorist" ban stop Palestine Action?

UK government seeks parliamentary approval to ban direct action protest group.

No truce on horizon as Gaza's children starve

Deadly ambush whips up dissent against “pointless” war.

CNN goes gentle on Genocide Gallant

Correspondents frequently ignored Palestinian deaths in Gaza in days after Israeli military’s attack on Iran.

Shipping giant Maersk supplies Israel with warplanes

Maersk quietly divests from illegal Israeli settlements.