Cryptocurrency is Deek’s last chance to succeed in life, and he will not stop, no matter what.

Previous Chapters: Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12 | Part 13| Part 14 | Part 15

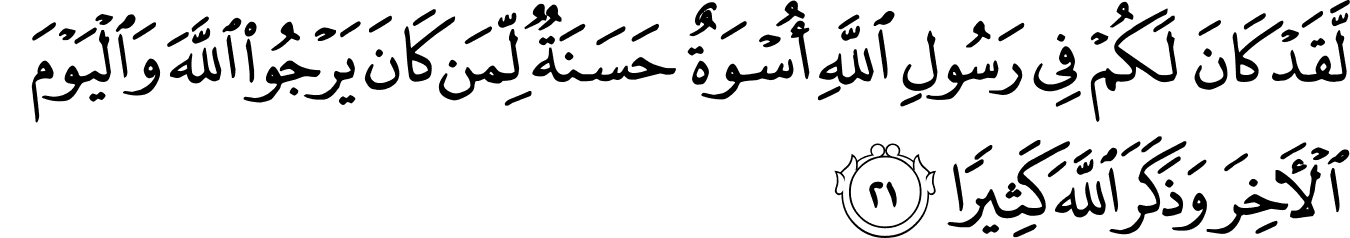

“Never say that those martyred in the cause of Allah are dead—in fact, they are alive! But you do not perceive it.”

– Quran 2:154

The Doors of Grace

Zaid Karim Al-Husayni walked in the door of his apartment and smiled, luxuriating in the aroma of Iraqi food that filled the place. He was bone tired, not so much physically, but emotionally. His heart was like an old rug, beaten to knock the dust off, only to find that the stains were permanent.

The apartment, at least, was a haven. Safaa had decorated it in the style of a traditional Arabic home. A low daybed beneath the window was piled with embroidered cushions in rose and cream, and a brass tray held Safaa’s silver teapot and two tiny glasses. Above, an ornate filigree lantern hung from the ceiling, casting warm light onto a mosaic-tiled floor of terracotta and cobalt.

The apartment, at least, was a haven. Safaa had decorated it in the style of a traditional Arabic home. A low daybed beneath the window was piled with embroidered cushions in rose and cream, and a brass tray held Safaa’s silver teapot and two tiny glasses. Above, an ornate filigree lantern hung from the ceiling, casting warm light onto a mosaic-tiled floor of terracotta and cobalt.

Safaa had done a phenomenal job. Zaid felt so at peace here.

“As-salamu alaykum,” he called out. “Bismillah, ya Allah iftah lee abwaba rahmatik.” O Allah, open for me the doors of your mercy.

The girls ran to greet him, and he dropped to one knee to embrace them. Anna was growing like a weed, and seemed taller every time he came home. She preferred plain clothes, like jeans and oversized t-shirts, and would not wear anything colorful or frilly. Hajar, on the other hand, looked like a wrapped dollop of sunshine in a ruffled yellow dress, and with a yellow ribbon in her hair.

“Guess what, Baba,” Anna said. She had begun calling him Baba unbidden about a year ago, and he never stopped her. She knew very well who her biological parents were, and she retained her given name – Anna Anwar. But for all genuine purposes, Zaid and Safaa were her parents now. Legally as well, since they had formally adopted her.

“Hajar says she wants to marry Ishaaq. I said she should find a boy with more qualities.”

“He has lots of qualities!” Hajar protested.

“Oh, really?” Zaid smiled. Ishaaq was a Yemeni boy in Hajar’s class. Zaid had always thought the two of them didn’t get along. “Like what?”

“Like he can draw a perfect circle, and he knows all the jokes.”

“Those qualities seem good.”

Hajar smiled. “You want to play Life with us?”

Zaid stood up, threw out his arms like an opera conductor and sang, “The game of Life, the gaaaaaame of Life, you will learn about life when you play the game of Life!”

Hajar threw back her head and laughed, while Anna said, “What is that, a commercial from the 1800’s?”

“You girls go play your game,” Safaa said. “Baba and I have to talk about grown up stuff.”

“Yucky,” Hajar commented, and the girls scampered off.

The Envelope

Safaa leaned in for a kiss. He pulled her close, embraced her and closed his eyes, reveling in her scent. He tightened his arms, squeezing her, and she gave a delighted laugh. When he released her she took his hand and said, “Come. I have something to show you.”

She led him to the bedroom, sat him on the bed and took an envelope out of a dresser drawer. “Deek Saghir stopped by. He dropped this off.”

Zaid took the envelope. It was heavy and full to bursting. He knew right away what was in it. On the front there was a note: For a true hero. The least I could do.

Zaid took the envelope. It was heavy and full to bursting. He knew right away what was in it. On the front there was a note: For a true hero. The least I could do.

Zaid’s mouth turned down, and a sour feeling rose in his gut. “Did you count it?”

“It’s one hundred thousand dollars.” She raised her eyebrows and grinned as if to say, Isn’t this an exciting development!

“I told him he only owed me $1,500. I’ll return the rest.”

Safaa sighed. “This again, baby? Why are you so determined to turn away money?”

Zaid’s mouth opened, then closed. He couldn’t tell her the details of what he’d done to rescue Deek. He couldn’t tell her that this was blood money. One hundred thousand? That was thirty three thousand per life taken. The cost of a new car. Was that what a human life was worth now, a car? If a man’s life was worth a mid-sized sedan then what about a child’s life? A scooter? The envelope felt like a brick of lead in his hands. He dropped it onto the bedspread.

Safaa studied him. She knew him well, and even though she didn’t know the details of what he’d done, she must have read some of it in his face. She took his hand gently.

“After you rescued Anna, I told you that you didn’t need me at all, that it was all of us who needed you, do you remember?”

“Sure.”

“Maybe that was true then. But now, baby, all we need is each other. You, me, Hajar and Anna. We don’t need this money. If you want to return it, I won’t object. But listen, sweetheart. This isn’t dirty money. It’s gratitude. You saved Deek in some kind of way, I know that. Every dollar in that envelope is a debt we all owe you, and you deserve every cent. I know you carry weight in your heart, but let me carry this one for you. I’ll take the money and spend it for our family, and I will carry the burden. I’m so proud of you—always.”

Zaid wanted to reply, but the words were caught in his chest like a butterfly in a net. He nodded.

Rather than embrace him, Safaa pushed him onto his back, straddled his torso and began to rain mock punches on his head. “Who’s the tough guy now, huh?”

Zaid laughed and called out for the girls. They came running, and he said, “Mama is beating me up, help!” With squeals of delight, the girls grabbed pillows and began to hit Safaa. The envelope fell off the bed and rolled under a nightstand. In that moment, Zaid forgot Deek, who was like a living Janus coin. He forgot Badger, and the teenage girl he’d returned home, and Bandar, and even Panama, and luxuriated in the joy of a moment like a precious pearl in a long string of gems. Allah had always been good to him, and always would be.

“I surrender!” Safaa pleaded. “Help, Zaid!”

He gave a mock villain’s laugh, and grabbed a pillow.

Letters and Books

He was still laughing when the cordless phone on the nightstand made a sound like a bird’s warble. He answered with a smile, but it faded as his father said, “As-salamu alaykum Zaid.” There was a softness to his tone that surprised Zaid, but worried him.

They’d spoken only once or twice since Zaid’s return from Panama. It wasn’t that Zaid blamed him for Mom’s behavior. Just that they had little to say to each other. After a lifetime of seeking attention from an emotionally absent father, a lifetime of hoping and wishing for a dad who would play with him, attend his school events, talk to him, notice him, Zaid had finally given up.

Although… His father had written to him regularly when he was in prison. They were not emotional, “I love you and stand by you,” kind of letters. That wasn’t his father’s style. More like, “I’m working on a major engineering project, your mother has been diagnosed with high blood pressure, Uncle Tarek sold the store…” That kind of thing. Yet even these dry notes were more than many had done, and – Zaid knew – were an expression of love.

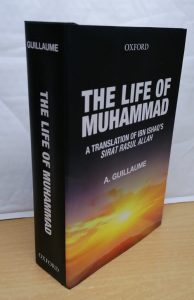

On top of that, his father had sent books. Every month, Zaid received a new book, and even though Zaid never requested any particular book, his father always seemed to send something appropriate. Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago, about the desperation of the Russian political prison system. A collection of Palestinian poetry of resistance. The incredibly detailed Life of Muhammad by A Guillaume. A sci-fi novel about a bodyguard pursued across multiple worlds by an alien race. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and Muhammad Asad’s Road to Mecca. And so on.

On top of that, his father had sent books. Every month, Zaid received a new book, and even though Zaid never requested any particular book, his father always seemed to send something appropriate. Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago, about the desperation of the Russian political prison system. A collection of Palestinian poetry of resistance. The incredibly detailed Life of Muhammad by A Guillaume. A sci-fi novel about a bodyguard pursued across multiple worlds by an alien race. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and Muhammad Asad’s Road to Mecca. And so on.

Zaid couldn’t keep more than five books in his cell by regulation, so he would read the books and then donate them to the prison library.

He still sometimes thought of that library, and what new prisoners must think coming into the pen and finding – instead of the usual collection of Louis L’Amour westerns – an eclectic collection of sci-fi books, Arab poetry, and Islamic treatises.

His father, absent though he may have been, had earned himself a lot of goodwill in Zaid’s heart with those letters and books.

Bad News

“Wa alaykum as-salam wa rahmatullah. It’s good to hear from you, Dad.” Saying this, Zaid realized that he sincerely meant it.

His father cleared his throat. “Thank you. I appreciate that. I have bad news, however.”

Panic rose like a geyser in Zaid’s chest. “Is it Mom?”

Safaa said something to the girls, and they trotted out. She closed the bedroom door, then returned to sit very close to Zaid, taking his hand.

“No,” his father said. “Baby Munir died last night. He went into a seizure and his heart stopped.”

The world narrowed. The breath he was about to take stalled. He heard something like an intake of air from the other side—maybe a sympathetic reflex, maybe nothing—and then his father continued, “Faiza called me this morning. She’s handling it. There will be a small memorial in Amman. I don’t know yet what the arrangements are. You can do whatever you think is appropriate.” His words were precise, like measurements on a blueprint—accurate and clear, with an almost imperceptible hint of concern.

Zaid didn’t speak for a long moment. There were more tears inside him than water in the Mediterranean, that warm and fruitful sea that kissed the shores of Gaza, but from which the Gazans were not allowed to fish.

The tears did not come, however. There would be a time for that.

“How is Aunt Faiza?” he asked finally, and the question came out smaller than the grief that had already rolled through him, and now lay like foam upon the surface of his inner sea.

“She’s keeping it together,” his father said. “She asked after you. Said you were the one who always talked to her when she needed to not fall apart.”

“Are we…” Zaid wasn’t sure what to ask. “Are we doing anything?”

“I cannot go to Amman right now, if that’s what you mean. You may do as you desire. Do what’s right.”

The “do what’s right” landed like a hand on his neck. Zaid had spent so much of his life trying to figure out what that phrase meant when it came from his father—was it obedience? Was it presence? Was it performance? He had no translator for grief that arrived wrapped in the same language that had once been a whip.

“I’ll see what I can do,” he said, and it came out brittle. His father made a small sound that could have been either acknowledgment or impatience.

“Take care of Safaa and the girls.”

“You take care as well,” Zaid managed, then realized that his father had already hung up.

Money’s Purpose

“What is it?” Safaa asked quietly.

“Baby Munir died.” The words were hollowed out by a lifetime of grief for his homeland and his relatives who had suffered and died. The old, complicated catalog of feelings—guilt, frustration, love, helplessness—rolled through him, heavy as the envelope that had tumbled under the nightstand and now lay somewhere out of sight.

The envelope! The money. His mind spun. The $100,000 had felt too heavy earlier, the numbers like a ledger of lives—how many had been paid for, how many had slipped away. Now the same stack of money was a bridge. Deek’s mess of debt and salvation folded back on itself: the man he’d pulled from the jaws of death had, without asking, given him the means to keep another small part of his own family from vanishing without acknowledgment.

Even as he thought this, his mind recognized the coldness of the mental arithmetic, and he recoiled. What was wrong with him? This wasn’t a trade: saving Deek’s life in exchange for a consolation prize for Faiza. Who was he to measure Allah’s grace, or to act as if he had a part in managing the balance? Astaghfirullah.

“Ya Allah,” he whispered, “Forgive me for counting what only You can weigh.” He let the impulse settle into something purer: he would send Aunt Faiza the money not to settle a debt or to manipulate the mizan – the heavenly scale that weighed all people’s deeds – but as an act of love. Nothing more..

Safaa put her arms around him, whispering Islamic prayers and words of comfort.

“I’m going to send Aunt Faiza thirty thousand dollars to cover the funeral costs, and to help with her living situation, inshaAllah.”

Safaa rubbed his back. “Of course, habibi. Whatever you want.”

“Allah have mercy on Deek Saghir,” Zaid said. “May Allah grant him good in the dunya and the aakhirah.”

“Ameen.”

Jamilah Al-Husayni

“I need to call Jamilah.” His cousin Jamilah Al-Husayni had a special fondness for Baby Munir. She deserved to know what had transpired.

Jamilah lived and worked in a rehab clinic on the Northern California coast.

Jamilah lived and worked in a rehab clinic on the Northern California coast. She returned every four or five months to visit her mother and brother in Madera, but no one knew her phone number and precise address except Zaid—‘for security,’ she’d insisted, because the patient she cared for needed privacy.

“You’re a private eye,” she’d once told him with a wink. “You know how to keep secrets. That’s why you’re the only one with my phone number. I expect discretion.”

Zaid had taken this act of trust seriously. Her number was saved in his contacts as simply “C” for cousin. As he pressed the call button, the room was quiet—only the soft rustle of the girls playing somewhere down the hall, the ordinary sound of life trying to push past the weight in the air.

Her voice came through, a little breathless. There was a whipping sound like a strong wind. “Zaid? Hold on, I’m sitting on the patio and the wind is coming off the ocean. Let me go inside.”

Zaid heard a door slide open and closed, and the background noise quieted. “It’s been too long. Where are you now?”

“In Fresno,” he said. “Home. Safaa is with me, you’re on speaker.”

“Safaa!” Jamilah exclaimed. “I miss you so much. We need to get together. How are the girls?”

Safaa’s tone was subdued, knowing what was coming. “They’re great, alhamdulillah. Anna calls us Baba and Mama now. Hajar wants to marry a boy named Ishaaq because he draws perfect circles.”

Jamilah laughed. “My cousin Shamsi has a checklist too, but that’s not on it.”

“I need to tell you something,” Zaid said. “It’s not good news.”

There was a pause, and when Jamilah spoke again her voice was subdued. “I think I know. Baby Munir returned to Allah, didn’t he?”

“Yes. Who told you?”

“No one. And I wasn’t actually sure.”

“He died last night. Allah have mercy on him,” Zaid said. “Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi rajioon.”

Without missing a beat, Jamilah recited an ayah from the Quran in Arabic, then translated:

“Never say that those martyred in the cause of Allah are dead—in fact, they are alive! But you do not perceive it.”

The ayah hit Zaid like a cold ocean wave, shocking him. SubhanAllah! His father had said that Munir had “died,” and Zaid had parroted the statement to Safaa and Jamilah. But no! We never speak of the shuhadaa that way. I know better. But sometimes I forget.

“You’re right,” he said. “Jamilah?”

The line went quiet, save for a faint hum that rose and fell. Had the line been disconnected? “Hello? Jamilah?” The sound continued. Safaa touched his arm and mouthed, “She’s crying.” Zaid closed his eyes, took a deep breath, and waited.

The Dream

Almost a full minute later, Jamilah spoke, and her voice was surprisingly strong. “The heart grieves, and the eyes weep, but we know the promise of Allah is true.”

Zaid mouthed the word, “Wow,” to Safaa. Who was this woman he was talking to? Jamilah had changed so much in the last few years. The younger Jamilah had been impulsive, angry, and sometimes arrogant, but this Jamilah was pious and wise beyond her years. His cousin kept a lot of secrets, but Zaid was sure that something profound must have happened to remake her in this way. “I knew something had happened,” Jamilah went on, “or was about to. I dreamed of baby Munir last night.”

“I knew something had happened,” Jamilah went on, “or was about to. I dreamed of baby Munir last night.”

Zaid didn’t expect the small hitch in his chest, the way his breath caught. “What did you see?”

“Falastin,” she said, and the word came out like a prayer. “Palestine. * (see author’s footnote). Not demolished homes and kids shot by snipers. Not murdered journalists, kidnapped children, bulldozed farms. No bombs falling. No. I saw a new Palestine being built in Jannah, block by block, street by street, town by town.

There is a new Falastin being built in Jannah, and it is glorious. Streets paved in gold bricks catch the sun and hold it like a promise. All the millions of Palestinians who hold keys to demolished or stolen houses? Those houses are being perfectly rebuilt with stones from the hills of Palestine. Everywhere there are arched doorways and domed roofs decorated with carved plaster swirls and rosettes. Courtyards with bubbling fountains, colorful tiles, and marble floors, and every home is finished with inlaid jewels and mother-of-pearl.

Families sit in their courtyards eating platters of grilled fish, musakhan, maqluba, bread, hummus, and olives. Children play football in the street, and these kids are strong and smiling, with eyes like bright stars.

There are vast orchards of tall olive trees, heavy with fruit. Cows and sheep graze the grass-covered hillsides. Fishermen return with great hauls of sea bream and sardines. Artisans make cheese, linen, and olive oil, just for the joy of it.

There are vast orchards of tall olive trees, heavy with fruit. Cows and sheep graze the grass-covered hillsides. Fishermen return with great hauls of sea bream and sardines. Artisans make cheese, linen, and olive oil, just for the joy of it.

No one is hungry, no one is frightened or grieving. Laughter, love, and dhikr fill the air, and the sun shines as gently as a kiss. All those who believed and did righteous deeds have gardens beneath which rivers flow, just as the Quran promises.

I was there. It is real. I stood there, on those streets. The air smelled like sea salt, fresh bread, za’tar, and jasmine. Everywhere I heard the sound of people reciting the Quran. The adhaan sounded from a shining silver masjid, and the sound was so sweet it made me weep. People streamed to the masjid from every direction, men in white thobes and kefiyyehs, women in traditional red and black dresses with tatreez embroidery. They strolled to the masjids happily, swinging their children, and praising Allah.”

“That’s incredible,” Zaid said. “That’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever heard.” Beside him, Safaa wept quietly, covering her mouth. He put an arm around her and held her tight.

Jamilah went on, and Zaid heard a tremor in her voice now. “Munir was there. I recognized him right away. He looked a lot like you, Zaid, when you were young. He wasn’t a baby, but a boy of ten years old, healthy and laughing. Thick brown hair and a big smile. He was doing a freestyle rap praising Allah, and other kids were standing around him, smiling and listening. He glanced my way and grinned, like he knew who I was.

And guys, those Palestinians… All the shuhadaa were there, and all who have been imprisoned and tortured, but they were whole people. They carried no weight, they weren’t healed because they were never broken. Because we Palestinians do not break.”

Still Me

Zaid didn’t answer immediately. The sound of his own breathing filled the silence, thick and raw. He felt something behind his eyes, warm and wet. He swallowed it down. “Tell Faiza,” he said. “Tell her what you saw. Let her know he’s somewhere better. That she’s not alone in carrying him.”

“I will,” Jamilah said. “I’ll call her tonight, inshaAllah.”

Zaid exhaled. “You’ve changed so much,” he said quietly. “Remember when I ran into you in San Francisco, and you were sitting on that armchair on the sidewalk, wearing your cycling outfit? Sometimes I miss the crazy Jamilah of the past, but I think the new Jamilah is a lot happier.”

He heard the sound of Jamilah’s smile. “There are places that try to break you, and places that build you back up. “I’m in a place that builds people back up. You’re right, I’ve changed. I was foolish and arrogant back then. I’m still me, Zaid. Just… Some of the edges have been softened. Things are clearer. Safaa, you’re so quiet. Are you still there?”

Safaa wiped her nose on Zaid’s sleeve, then said, “You’re a special person, Jamilah.”

“And you, Safaa, are the rock that my cousin leans on, and the light that shows the way.”

Safaa smiled and brushed tears from her cheeks.

“Should we do something for Faiza?” Jamilah wanted to know.

“I’ve got it covered,” Zaid said. “I’m sending her a good amount of money. Courtesy of a brother named Deek Saghir.”

“In that case,” Jamilah said, “Allah barik feek, ya Deek Saghir. Allah bless you, whoever you are.”

After the call, Zaid remained sitting, thinking about Jamilah’s dream. Allah had given her a true dream, which was one of the signs of imaan. He felt it acting as a salve inside him, softening the ragged edges of his wounds. He clung to it as a talisman, believing in it fully.

The dream did not erase the suffering of the Palestinians. The evil being committed against his people was unfathomable. But after all he’d been through, Zaid had come to grasp a certain truth: the dunya did not make sense without the aakhirah. In the dunya, people sometimes got away with their crimes, and innocents died without recompense.

By changing the time scale, by adding a dimension to human existence, and by factoring in a Day of perfect judgment when every stone and tree would be a witness, the aakhirah changed everything.

* * *

Footnote: this dream of Falastin in Jannah was dreamed by one of the residents of Gaza a few months ago. It was narrated to me by someone who heard it from that person. It was specifically a dream of a new Gaza being built in Jannah. I fully believe it to be true. In this story I changed it to Palestine more generally.

[Part 17 will be published next week inshaAllah]

Reader comments and constructive criticism are important to me, so please comment!

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s other stories on this website.

Wael Abdelgawad’s novels – including Pieces of a Dream, The Repeaters and Zaid Karim Private Investigator – are available in ebook and print form on his author page at Amazon.com.

Related:

Gravedigger: A Short Story

The Deal : Part #1 The Run

The post Moonshot [Part 16] – A Palestine In Paradise appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

.

. Promise that a life lived in dignity and in defence of the oppressed, is far more valuable than anything else. Haya herself maintained that while she would always fight her suspension, she would never apologise for her advocacy of the Palestinian people.

Promise that a life lived in dignity and in defence of the oppressed, is far more valuable than anything else. Haya herself maintained that while she would always fight her suspension, she would never apologise for her advocacy of the Palestinian people. will make me a man of my word, and because I had promised this, I decided that I would actually follow through. But, in the process of going further and seeking to rescind the degree, I came upon a different motivation for myself; one that desired to divest from these institutions and the stranglehold they have over what we consider to be a dignified and honoured life. That the Master’s degree means nothing to me in the midst of a genocide – that there is nothing that the accolade was able to give me that I could not have learnt from a book.

will make me a man of my word, and because I had promised this, I decided that I would actually follow through. But, in the process of going further and seeking to rescind the degree, I came upon a different motivation for myself; one that desired to divest from these institutions and the stranglehold they have over what we consider to be a dignified and honoured life. That the Master’s degree means nothing to me in the midst of a genocide – that there is nothing that the accolade was able to give me that I could not have learnt from a book. accepts it – what is more valuable now? The du’as of the oppressed, or the certificate from a colonial institution invested in a racially segregated apartheid state? I haven’t come to think of it as a sacrifice, as much as it now feels liberatory.

accepts it – what is more valuable now? The du’as of the oppressed, or the certificate from a colonial institution invested in a racially segregated apartheid state? I haven’t come to think of it as a sacrifice, as much as it now feels liberatory.

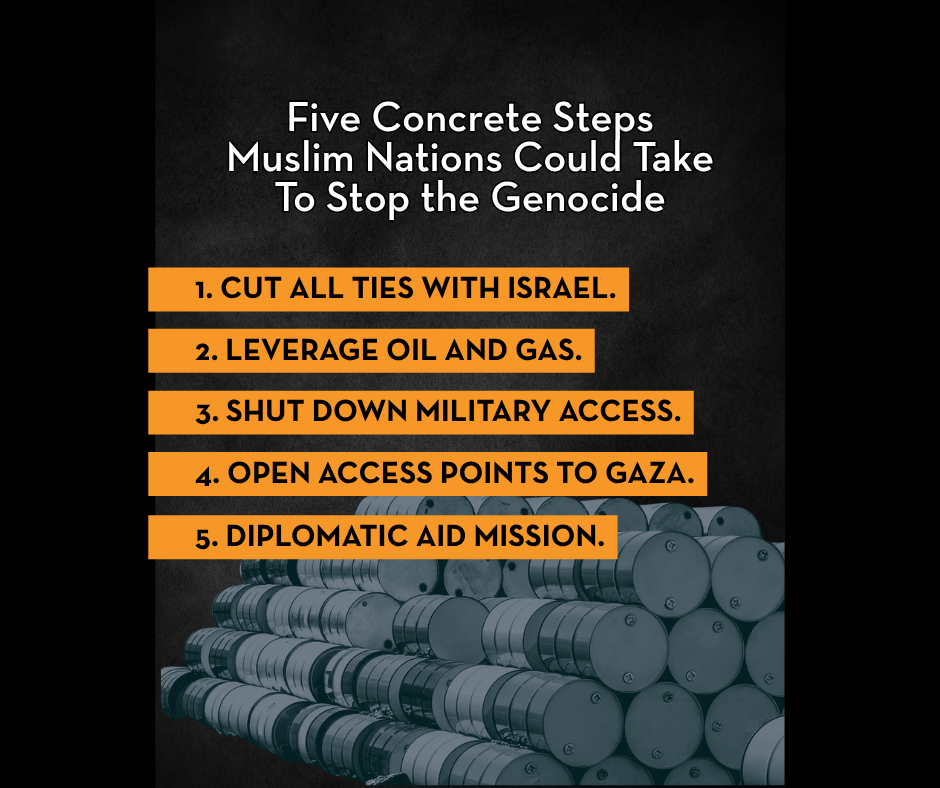

. So should the fate of Palestine, including Masjid Al Aqsa.

. So should the fate of Palestine, including Masjid Al Aqsa.

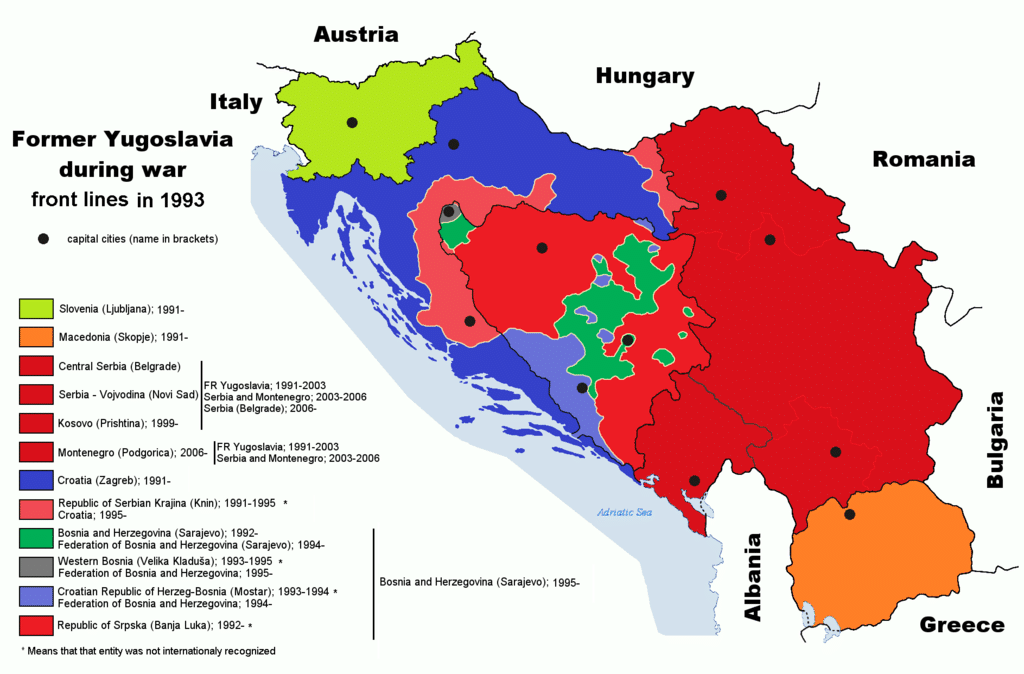

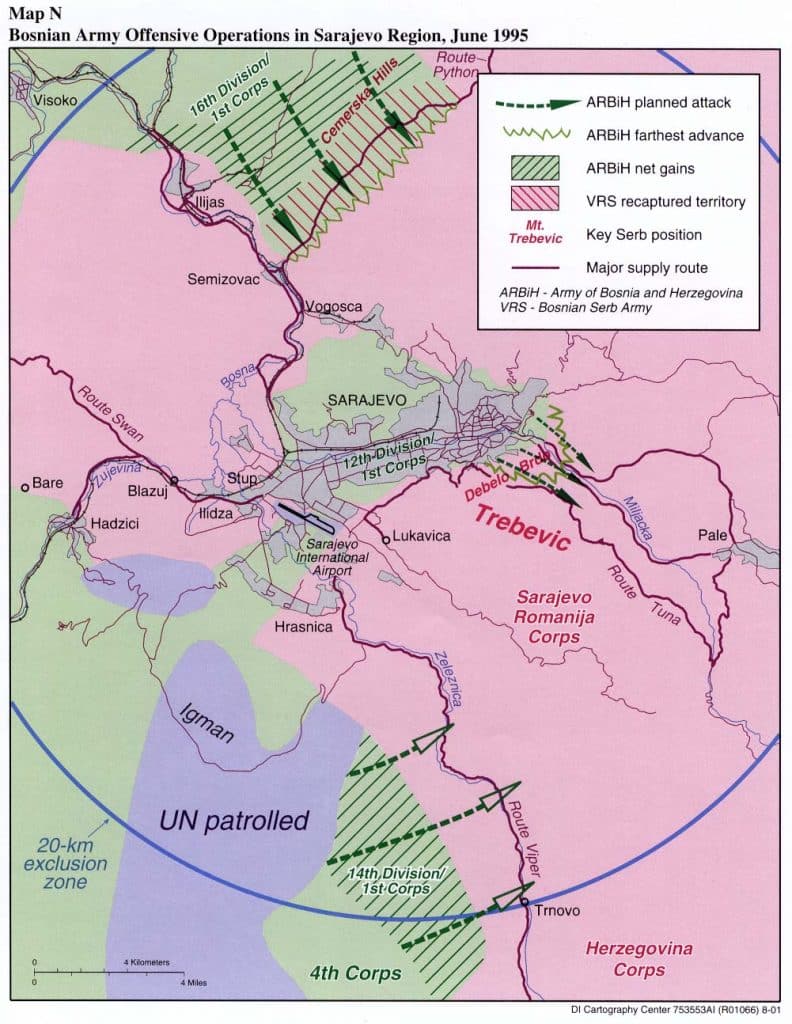

“While it has been [30] years since the war and genocide, the Bosnian population remains unhealed and too traumatized to speak publicly of the horrors they lived through,” the author’s note prefaced (Buljušmić-Kustura, 12). This statement echoes again in multiple letters. Rabija, whose first letter serves as an introduction to the silence surrounding the Bosnian genocide as a whole said, “We are afraid and yet we speak very little about the fear that we feel. I often wonder if my Bosnian friends do not speak about our past for fear it will repeat itself again.” (Buljušmić-Kustura, 21-22)

“While it has been [30] years since the war and genocide, the Bosnian population remains unhealed and too traumatized to speak publicly of the horrors they lived through,” the author’s note prefaced (Buljušmić-Kustura, 12). This statement echoes again in multiple letters. Rabija, whose first letter serves as an introduction to the silence surrounding the Bosnian genocide as a whole said, “We are afraid and yet we speak very little about the fear that we feel. I often wonder if my Bosnian friends do not speak about our past for fear it will repeat itself again.” (Buljušmić-Kustura, 21-22)

As a millennial Muslim woman, I am very familiar with the memoir-like narratives of my peers, but rarely do I see reflective pieces by Muslim men… so when I received an ARC of this book, I was excited. I want to know more about Muslim men’s experiences with faith & fatherhood & being Muslim in a non-Muslim land.

As a millennial Muslim woman, I am very familiar with the memoir-like narratives of my peers, but rarely do I see reflective pieces by Muslim men… so when I received an ARC of this book, I was excited. I want to know more about Muslim men’s experiences with faith & fatherhood & being Muslim in a non-Muslim land. “Bigger Than Divorce” by Makeda Yasenlul is a pretty unique book in the Muslamic genre, being the only book I’ve come across so far that talks about divorce (or rather, living the aftermath of divorce) to a Muslim female audience.

“Bigger Than Divorce” by Makeda Yasenlul is a pretty unique book in the Muslamic genre, being the only book I’ve come across so far that talks about divorce (or rather, living the aftermath of divorce) to a Muslim female audience. Following two Palestinian cousins, Yasmine – living in Canada – and Reem – living in a refugee camp in Lebanon, this story covers multiple themes (sometimes to its own detriment). From Palestinian grief to an abusive marriage, from missing family members and mysterious letters (and also a K-drama actor Muslim convert), this book never quite figures itself out. (Also, the blurb calls this a “political historical thriller and a Muslim feminist love story.” It is neither.)

Following two Palestinian cousins, Yasmine – living in Canada – and Reem – living in a refugee camp in Lebanon, this story covers multiple themes (sometimes to its own detriment). From Palestinian grief to an abusive marriage, from missing family members and mysterious letters (and also a K-drama actor Muslim convert), this book never quite figures itself out. (Also, the blurb calls this a “political historical thriller and a Muslim feminist love story.” It is neither.)

Muslim Youth Musings is a fantastic literary organization for aspiring Muslim writers mashaAllah – and they’ve just published their first anthology!

Muslim Youth Musings is a fantastic literary organization for aspiring Muslim writers mashaAllah – and they’ve just published their first anthology! “Odd Girl Out” by Tasneem Abdur-Rashid is a great Muslamic take on quintessential YA: a teenager going through big life changes, dealing with the drama… and in this case, also facing Islamophobia.

“Odd Girl Out” by Tasneem Abdur-Rashid is a great Muslamic take on quintessential YA: a teenager going through big life changes, dealing with the drama… and in this case, also facing Islamophobia. The Amina Banana series is an early chapter book series following Amina, a young Syrian girl who has recently moved to America. She tries to overcome different challenges by coming up with secret formulas – in book one, for friendship, and in book two, for winning the spelling bee.

The Amina Banana series is an early chapter book series following Amina, a young Syrian girl who has recently moved to America. She tries to overcome different challenges by coming up with secret formulas – in book one, for friendship, and in book two, for winning the spelling bee.

when she cried out in labor beneath the palm. It never turned away Khadijah’s

when she cried out in labor beneath the palm. It never turned away Khadijah’s  wisdom, or Ali’s

wisdom, or Ali’s