Aggregator

Malaysian shop chain that sold ‘Allah socks’ targeted with petrol bombs

Three stores hit with molotov cocktails after pictures of socks deemed offensive by Muslims shared on social media

Three stores belonging to a Malaysian minimart chain that sold socks carrying the word “Allah” have been targeted with molotov cocktails over the past week, in a rare case of such violence.

One of KK Super Mart’s stores in Kuching, the capital of Sarawak, in Malaysian Borneo, was hit by a molotov cocktail on Sunday, a day after a separate attack on a store in Pahang on the east coast of peninsular Malaysia. On 26 March, a store in Perak was also targeted with a petrol bomb, though it did not ignite, according to local media.

Continue reading...‘Not even water?’: Ramadan radio show demystifies Dutch Muslim life

All-female lineup of presenters hope to break harmful Islamic stereotypes after Geert Wilders’ election victory

An hour before dawn in a nondescript building in Hilversum, a sleepy town half an hour south of Amsterdam, Nora Akachar grabs the microphone. There is nothing unique about a radio host summoning the nation out of its slumber. But this is, in her own words, “a big deal”.

The Dutch Moroccan actor turned radio host is live on air presenting Suhoor Stories, a talk radio show presented by seven Dutch Muslim women, inviting Muslim guests to demystify Ramadan for the wider public. The programme is believed to be Europe’s only daily Ramadan radio and television show aired by a national public broadcaster.

Continue reading...A Ramadan Quran Journal: A MuslimMatters Series – [Juz 18] The Bird

This Ramadan, MuslimMatters reached out to our regular (and not-so-regular) crew of writers asking them to share their reflections on various ayahs/surahs of the Quran, ideally with a focus on a specific juz – those that may have impacted them in some specific way or have influenced how they approach both life and deen. While some contributors are well-versed in at least part of the Quranic Sciences, not all necessarily are, but reflect on their choices as a way of illustrating that our Holy Book is approachable from various human perspectives.

Introducing, A Ramadan Quran Journal: A MuslimMatters Series

***

The Birdby Wael Abdelgawad

Flying over the ocean off the coast of the great central land – what the humans called Africa, though the bird did not know this – the albatross heard the sound of a boy reciting the Quran. The sound arrived on the wind like a righteous stowaway, faint but discernible. The wind was like that. It could carry the sound of a bird’s cry across a vast distance, or could snatch away and conceal even the most terrible noises.

Wind was something the albatross understood better than any living creature.

The great bird was a glider, with a wingspan of four meters. He knew air currents as he knew his own heartbeat. He could travel 100 kilometers without flapping his wings, using techniques such as dynamic soaring, in which he expertly flew into an air current to gain elevation, turned, and dropped in elevation to survey for fish. If he saw a school of fish he would dive straight into the wild sea and snatch one up. In fact, his name, albatross, came from the Arabic al-ġaṭṭās, ‘the diver’, though the bird did not know this.

Special tendons in the albatross’s shoulders held his wings extended without effort. He could travel a thousand kilometers in a day – nearly the distance between Madinah and Amman, both of which he had visited. His habitat was the entire southern hemisphere of the world, and he had crossed it multiple times.

The albatross knew the Quran as well, as did all living things, for did Allah  not say that the Prophet Muhammad

not say that the Prophet Muhammad  – and therefore the Quran that he brought – was a mercy to all the worlds? And was not Allah

– and therefore the Quran that he brought – was a mercy to all the worlds? And was not Allah  the Lord of all the worlds? And did this not include the animal world? Oh, the albatross did not understand the linguistic meaning of the Arabic words, but the Quranic essence flowed into his heart as easily as the wind flowed over the sea.

the Lord of all the worlds? And did this not include the animal world? Oh, the albatross did not understand the linguistic meaning of the Arabic words, but the Quranic essence flowed into his heart as easily as the wind flowed over the sea.

He glided in toward shore, drawn by the recitation, coming in fast and low toward the emerald hills of Cape Town, South Africa.

The boy who recited the Quran was small and brown-skinned, wearing loose white clothing and a white cap with gold embroidery. He sat cross-legged and barefoot on the bow of a sailing boat that was tethered to the dock, and held the mushaf in his lap, reciting Surat An-Nur out loud.

Albatross (PC: Paul Carroll [unsplash])

The albatross extended his talons and landed smoothly on the top mast of the boat. Folding his great wings into his sides, he settled himself to listen.Perhaps having caught a glimpse of motion through his peripheral vision, the boy looked up, startled, and gaped.

The albatross knew he was an unusual sight. There were not many of his kind left, the majority of his race having been destroyed by human poachers, poisoned by pollution, killed by cats or rats as chicks, starved by human overfishing of the seas, or caught in fishing nets and hooks. He was a grizzled old survivor, over forty years old, though the bird himself could not count. He only knew that he had survived his brood, his pair-bonded mate, and probably most of his own chicks.

The boy called out words that the albatross did not understand, but – having had much experience with humans – guessed was probably something like, “Baba, there is a big bird!”

A voice from the ship’s hold replied gruffly, maybe saying, “So what? Birds are everywhere. Continue your recitation.”

Reluctantly, the boy tore his eyes from the great albatross and chanted:

- Allāh is the Light of the heavens and the earth. The example of His light is like a niche within which is a lamp; the lamp is within glass, the glass as if it were a pearly [white] star lit from [the oil of] a blessed olive tree, neither of the east nor of the west, whose oil would almost glow even if untouched by fire. Light upon light. Allāh guides to His light whom He wills. And Allāh presents examples for the people, and Allāh is Knowing of all things.

The bird exhaled softly through his nostrils, thinking, subhanAllah! What glory, what beauty! He knew well that Allah  was the light of the heavens and earth, for was it not Allah

was the light of the heavens and earth, for was it not Allah  who guided him on his journeys? Wasn’t it Allah

who guided him on his journeys? Wasn’t it Allah  who brought him through lightning and storm, across vast distances of open ocean, and across great landmasses, even as the humans polluted the world with noise and artificial light? Wasn’t it Allah

who brought him through lightning and storm, across vast distances of open ocean, and across great landmasses, even as the humans polluted the world with noise and artificial light? Wasn’t it Allah  who controlled the sun, moon and stars, by which the albatross navigated?

who controlled the sun, moon and stars, by which the albatross navigated?

The bird understood that the lamp in the niche was the heart of the believer, which is filled with the light of Allah  , and is naturally inclined to Allah

, and is naturally inclined to Allah  . As for the light upon light, it might be the light of the Quran, and the light of faith. And Allah

. As for the light upon light, it might be the light of the Quran, and the light of faith. And Allah  knew best.

knew best.

- In houses which Allāh has ordered to be raised and that His name be mentioned therein; exalting Him within them in the morning and the evenings…

- [are] men who neither commerce nor sale distracts from the remembrance of Allāh and performance of prayer and giving of zakāh. They fear a Day in which the hearts and eyes will [fearfully] turn about –

- That Allāh may reward them [according to] the best of what they did and increase them from His bounty. And Allāh gives provision to whom He wills without account [i.e., limit].

The albatross was an observer of human beings by necessity, for in their hands lay the survival of all earthly life. And they were making a cruel mess of it. But yes, he had seen men and women who worshiped Allah  , dedicated themselves to righteousness, and harmed no living thing. Such people were uncommon strangers in this world. May Allah

, dedicated themselves to righteousness, and harmed no living thing. Such people were uncommon strangers in this world. May Allah  have mercy on them and reward them.

have mercy on them and reward them.

The boy recited:

- But those who disbelieved – their deeds are like a mirage in a lowland which a thirsty one thinks is water until, when he comes to it, he finds it is nothing but finds Allāh before him, and He will pay him in full his due; and Allāh is swift in account.

The albatross was once blown far off course by a storm, and found himself over deep desert. He flew for days, riding the eddies, using a technique known as slope gliding to stay in the air. He became desperately thirsty, and on the fourth day saw a shimmering lake of blue amid the vast expanse of sand. He landed, only to find dry dust. In frustration and desperation, he took a bill full of sand, only to choke on it. If such were the deeds of the disbelievers, then he thanked and praised Allah  that he was not one of them.

that he was not one of them.

- Or [they are] like darknesses within an unfathomable sea which is covered by waves, upon which are waves, over which are clouds – darknesses, some of them upon others. When one puts out his hand [therein], he can hardly see it. And he to whom Allāh has not granted light – for him there is no light.

Ths ayah made the bird’s breath catch, for it took him back to another experience of his in which he’d been shot and nearly killed. He’d been far out over the deep ocean on a windy, pitch black night, in which there was no moon, and heavy clouds blocked the stars. Albatrosses could float upon the ocean when tired, but on this night it was not possible, for the sea was in turmoil, with massive waves rising up and crashing down. It could be difficult to navigate on such nights, and the inky darkness weighed on one’s spirit. An albatross’s life was lonely, but nights like that reminded him of all he had lost. If such was the soul of the disbeliever, it was a frightful way to live.

On that particular night, he spotted one of the immense, brightly lit container ships plying the sea, rocking with the waves, but large enough to stay afloat. It was a welcome sight, and he landed atop the pilot house to rest. As he sat, wings folded, head tucked into his feathers, he heard an odd sound. Lifting his head, he saw an unlit boat approaching rapidly. Knowing this was not normal, he took flight, as the conflicts of men were not his affair.

Circling above, he watched as human death sticks chattered and flamed, men yelled and screamed, and the container ship caught fire. A loud explosion made his heart race, and the container ship began to list. Men were washed overboard. A stray bullet – a hot stone in his understanding – clipped his wing and he cawed in pain. Cursing himself for his curiosity he sped away, his wing dripping blood. The last thing he saw was the container ship sinking into the frigid, uncaring sea.

The boy’s recitation brought him back:

- Do you not see that Allāh is exalted by whomever is within the heavens and the earth and [by] the birds with wings spread [in flight]? Each [of them] has known his [means of] prayer and exalting [Him], and Allāh is Knowing of what they do.

- And to Allāh belongs the dominion of the heavens and the earth, and to Allāh is the destination.

This verse made joy geyser in the albatross’s heart, for it spoke of him! It was true, he did indeed exalt and praise Allah  , Master of the sky and sea and stars, Creator of all, and the sole Provider. Excited to hear himself mentioned, the albatross spread his wings wide.

, Master of the sky and sea and stars, Creator of all, and the sole Provider. Excited to hear himself mentioned, the albatross spread his wings wide.

The boy stopped his recitation and looked worriedly at the bird. Seeing this, the albatross tucked his wings again and settled down.

Hesitantly, the boy continued:

- Do you not see that Allāh drives clouds? Then He brings them together; then He makes them into a mass, and you see the rain emerge from within it. And He sends down from the sky, mountains [of clouds] within which is hail, and He strikes with it whom He wills and averts it from whom He wills. The flash of its lightning almost takes away the eyesight.

- Allāh alternates the night and the day. Indeed in that is a lesson for those who have vision.

The albatross was excited. Clouds, rain, hail, and lightning, were part of his daily experience. They were his reality, for good or bad.

The humans were free creatures, but they did not know they were free. In giving them free agency, Allah  had elevated them, making their ‘ibadah precious. And in giving them khilafah over the earth, Allah

had elevated them, making their ‘ibadah precious. And in giving them khilafah over the earth, Allah  had enabled them to create a world of gardens and peace. Yet they chained themselves to meaningless possessions and killed each other out of greed. They lived in the muck, scrabbling and bleeding, forgetting how Allah

had enabled them to create a world of gardens and peace. Yet they chained themselves to meaningless possessions and killed each other out of greed. They lived in the muck, scrabbling and bleeding, forgetting how Allah  had honored them.

had honored them.

The albatross, on the other hand, was absolutely free, in the physical sense. He had seen the way fishermen and beachgoers gazed at him in longing, faces upturned, wishing they could fly as he did. Yet he was old and weary of contending with storms, waves, and hunger. He yearned for a safe place he could call home.

He was not a creature of will, however, and could not change his nature.

With these turbulent thoughts and emotions running through his mind, the albatross opened his mouth and uttered the characteristic – and very loud – call of his kind: “UWAY, UWAY, taak tak tak tak tak tak tak tak tak tak tak!”

It was too much for the boy. He closed the Quran and ran into the boathouse, calling out for his parents.

Ah well. The albatross preened his feathers for a moment, then stretched out his wings, flapped a few times, and found an air current. Banking into it, he climbed quickly and steered toward the rough waters off the coast of Cape Agulhas. The yellowtail and snoek were shoaling at this time of year, and he would have a fish in his belly soon enough, inshaAllah.

THE END

***

Reader comments and constructive criticism are important to me, so please comment!

See the Story Index for Wael Abdelgawad’s fiction stories on this website.

Wael Abdelgawad’s novels – including Pieces of a Dream, The Repeaters and Zaid Karim Private Investigator – are available in ebook and print form on his author page at Amazon.com.

Related:

– A Ramadan Quran Journal: A MuslimMatters Series – [Juz 17] Trust Fund And A Yellow Lamborghini

–

The post A Ramadan Quran Journal: A MuslimMatters Series – [Juz 18] The Bird appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Al-Shifa Hospital in ruins

Hundreds were executed, patients left to die during Israel’s two-week siege.

A small oasis of green in Gaza

Nafeez Ahmed Seeks to Explain His Actions Re: MYH Scandal

Letter Received from Lawyers for former MYH CEO Akeela Ahmed

A Whistleblower and the Muslim Youth Helpline

The Origin And Evolution Of The Taraweeh Prayer

During the month of Ramadan, Muslims worldwide engage in a special night prayer known as Taraweeh. In this article, I will delve into the history of this practice.

As Muslims, we perform the obligatory five daily prayers, with the last one being the Isha prayer. However, we are also encouraged to engage in additional night prayers. While these night prayers are considered voluntary, they are highly recommended.

Allah  praises devout believers, describing them as those who pray at night, seeking forgiveness in the hours just before dawn, known as the sahr hours. In the Quran, Allah

praises devout believers, describing them as those who pray at night, seeking forgiveness in the hours just before dawn, known as the sahr hours. In the Quran, Allah  said:

said:

“They arise from [their] beds; they supplicate their Lord in fear and aspiration, and from what We have provided them, they spend.” [Surah As-Sajdah: 32;16]

And further Allah  said:

said:

“They used to sleep but little of the night. And in the hours before dawn they would ask forgiveness.” [Surah Adh-Dhariyat: 51;17-18]

“They used to sleep but little of the night. And in the hours before dawn they would ask forgiveness.” [Surah Adh-Dhariyat: 51;17-18]

Night Prayers

Night Prayers

The Messenger of Allah  , peace be upon him, consistently engaged in night prayers. He typically prayed alone rather than in congregation (Jama’ah). Occasionally, he would come out to the mosque, and on such occasions, people might join him. There is a hadith that reports Ibn Abbas sleeping over at the house of the Messenger of Allah

, peace be upon him, consistently engaged in night prayers. He typically prayed alone rather than in congregation (Jama’ah). Occasionally, he would come out to the mosque, and on such occasions, people might join him. There is a hadith that reports Ibn Abbas sleeping over at the house of the Messenger of Allah  and joining him in a night prayer. Some of the Sahaba also used to join Prophet Muhammad

and joining him in a night prayer. Some of the Sahaba also used to join Prophet Muhammad  in night prayers whenever they witnessed him praying in the mosque.

in night prayers whenever they witnessed him praying in the mosque.

Night Prayers in Ramadan at the Time of the Prophetعَنْ أَبي عبدِ الله حُذيفةَ بنِ اليمان، رضي اللهُ عنهما قال: صَلَّيتُ مع النَّبيِّ صلَّى اللهُ عليه وسلَّم ذاتَ ليلةٍ، فافتتح البقرةَ، فقلتُ يركعُ عند المائة، ثم مضَى فقلتُ يصلِّي بها في ركعةٍ، فمَضَى، فقلتُ يركعُ بها، ثم افتتح النساءَ: فقرأها، ثمَّ افتتحَ آل عمرانَ فقرأها، يقرأُ مترسلًا، إذا مرَّ بآيةٍ فيها تسبيحٌ سبَّحَ، وإذا مرَّ بسؤالٍ سألَ، وإذا مرَّ بتعوذٍ تعوَّذَ، ثم ركع فجعلَ يقولُ: « سبحانَ ربي العظيم» فكان ركوعه نحوًا من قيامه، ثم قال: «سمع اللهُ لمن حمِدَه، ربنا ولك الحمد» ثم قام قيامًا قريبًا مما ركع، ثم سجد فقال: «سبحان ربي الأعلى» فكان سجوده قريبًا من قيامه. رواه مسلم.

Hudaifa ibn Alyaman said I prayed one night with the Prophet, peace and blessings be upon him. The Prophet started reciting al-Baqarah and I thought he would stop after 100 verses. But when he went beyond it I thought that he may want to recite the whole chapter in one Rakah. When he finished al-Baqarah I thought he would do Ruku but then he immediately started reciting al-Imran and when he finished he started reciting an-Nisa.

The Prophet was reciting very slowly with enough pauses and would do Tasbeeh (praising God) and Dua (supplication) according to the subject being discussed in the relevant Ayah.

After that the Prophet did Ruku. In Ruku he stayed as long as he did when he was in Qiyam (standing in prayer). After Ruku he stood up for almost the same time and then he performed Sajdah (prostration) and stayed there as long as he recited Quran while doing Qiyam.”

[Hudaifa

, narrated this hadith as in Sahih al Muslim]

During the era of the Prophet  , in Ramadan and after the Isha prayer, there was no unified congregation prayer. Muslims had the flexibility to either pray night prayer at home or in the masjid. It was reported in a Hadith, that the Prophet

, in Ramadan and after the Isha prayer, there was no unified congregation prayer. Muslims had the flexibility to either pray night prayer at home or in the masjid. It was reported in a Hadith, that the Prophet  , used to encourage them to stand in prayers in Ramadan without strongly ordering them to do so, he

, used to encourage them to stand in prayers in Ramadan without strongly ordering them to do so, he  said: “Whoever performs Ramadan out of faith and seeking reward from Allah, his previous sins will be forgiven.” [Sahih al-Bukhari 1901]

said: “Whoever performs Ramadan out of faith and seeking reward from Allah, his previous sins will be forgiven.” [Sahih al-Bukhari 1901]

Abu Salamah ibn ‘Abd ar-Rahmaan, said he asked ‘Aa’ishah  : “‘How did the Messenger of Allah

: “‘How did the Messenger of Allah  pray during Ramadan?’ She said: ‘He did not pray in Ramadan or at any other time, more than eleven Rakat. He would pray four, and do not ask how beautiful and long they were. Then he would pray four, and do not ask how beautiful and long they were. Then he would pray three Rakat.’” [Sahih; Sunan an-Nasa’i 1697]

pray during Ramadan?’ She said: ‘He did not pray in Ramadan or at any other time, more than eleven Rakat. He would pray four, and do not ask how beautiful and long they were. Then he would pray four, and do not ask how beautiful and long they were. Then he would pray three Rakat.’” [Sahih; Sunan an-Nasa’i 1697]

So Muslims used to pray Isha and after that there was no one unified congregation prayer. Some used to go home and pray there, some would sleep and wake up again to pray at either their home or in the masjid.

This practice remained until one night during Ramadan before the death of the Prophet  , he came out and prayed the night prayer at the Masjid. Some Companions joined him in that night prayer. However, after a few nights, he didn’t come out to them as narrated by A’isha

, he came out and prayed the night prayer at the Masjid. Some Companions joined him in that night prayer. However, after a few nights, he didn’t come out to them as narrated by A’isha  . Once in the middle of the night the Messenger of Allah

. Once in the middle of the night the Messenger of Allah  , went out and prayed in the mosque and some men prayed with him. The next morning the people spoke about it and so more people gathered and prayed with him. They circulated the news in the morning, and so, on the third night the number of people increased greatly. The Messenger of Allah

, went out and prayed in the mosque and some men prayed with him. The next morning the people spoke about it and so more people gathered and prayed with him. They circulated the news in the morning, and so, on the third night the number of people increased greatly. The Messenger of Allah  , came out and they prayed behind him. On the fourth night, the mosque was overwhelmed by the people until it could not accommodate them. The Messenger of Allah

, came out and they prayed behind him. On the fourth night, the mosque was overwhelmed by the people until it could not accommodate them. The Messenger of Allah  came out only for the Fajr prayer and when he finished the prayer, he faced the people and said, “I knew about your presence, but I was afraid that this prayer might be made compulsory and you might not be able to carry it out.” The Messenger of Allah

came out only for the Fajr prayer and when he finished the prayer, he faced the people and said, “I knew about your presence, but I was afraid that this prayer might be made compulsory and you might not be able to carry it out.” The Messenger of Allah  died and the matter remained the same. [Sahih al-Bukhari 2012]

died and the matter remained the same. [Sahih al-Bukhari 2012]

This cautious approach was consistent with the Prophet’s  habit of sometimes leaving certain good deeds, even though he loved them, fearing they might become compulsory for the people. As it was narrated by A’isha, that “Allah’s Messenger

habit of sometimes leaving certain good deeds, even though he loved them, fearing they might become compulsory for the people. As it was narrated by A’isha, that “Allah’s Messenger  used to give up a good deed, although he loved to do it, for fear that people might act on it and it might be made compulsory for them.” [Sahih al-Bukhari 1128]

used to give up a good deed, although he loved to do it, for fear that people might act on it and it might be made compulsory for them.” [Sahih al-Bukhari 1128]

So what he  did in Ramadan was a continuation of that habit. He

did in Ramadan was a continuation of that habit. He  did not continue praying so it wouldn’t be compulsory upon the people.

did not continue praying so it wouldn’t be compulsory upon the people.

Pray at Night?

Pray at Night?

As mentioned in a previous hadith by A’isha  , the Prophet

, the Prophet  used to pray eight Rakats both in Ramadan and outside of it. This practice is further affirmed by a narration from Jabir bin Abdullah

used to pray eight Rakats both in Ramadan and outside of it. This practice is further affirmed by a narration from Jabir bin Abdullah  , who specifically mentioned the number of Rakat that the Prophet

, who specifically mentioned the number of Rakat that the Prophet  prayed in Ramadan. Jabir Bin Abdullah

prayed in Ramadan. Jabir Bin Abdullah  said that “the Prophet ﷺ led us in prayer in Ramadan eight Rakat then on the following night we gathered but he did not come out to us till morning. When he was asked he said ‘I was afraid it would be written upon you,’ meaning it would become compulsory upon you.”

said that “the Prophet ﷺ led us in prayer in Ramadan eight Rakat then on the following night we gathered but he did not come out to us till morning. When he was asked he said ‘I was afraid it would be written upon you,’ meaning it would become compulsory upon you.”

Death

Death

After the passing of the Prophet  , people continued to pray night prayers either individually or in separate groups.

, people continued to pray night prayers either individually or in separate groups.

This pattern continued during the time of Abu Bakr  , and the early time of Omar, may Allah

, and the early time of Omar, may Allah  be pleased with him.

be pleased with him.

PC: Salman Preeom (unsplash)

The decision of the Prophet  not to gather people under one Imam for night prayers, fearing its potential obligation on the Ummah, no longer applied after his death. With the establishment of the Sharia, this concern ceased to exist. Omar ibn Al-Khattab

not to gather people under one Imam for night prayers, fearing its potential obligation on the Ummah, no longer applied after his death. With the establishment of the Sharia, this concern ceased to exist. Omar ibn Al-Khattab  recognized this change in circumstances and, as a result, initiated the congregational Taraweeh prayer under one imam.

recognized this change in circumstances and, as a result, initiated the congregational Taraweeh prayer under one imam.

This decision marked a significant shift from the previous practice. The rationale behind the Prophet’s  caution was no longer applicable, paving the way for the community to come together under a single Imam for the Taraweeh prayers during the time of Omar ibn Al-Khattab

caution was no longer applicable, paving the way for the community to come together under a single Imam for the Taraweeh prayers during the time of Omar ibn Al-Khattab  .

.

Al-Bukhaari narrated from ‘Abd ar-Rahmaan ibn ‘Abd al-Qaari’ that he said: ‘I went out with ‘Umar ibn al-Khattaab (may Allah be pleased with him) one night in Ramadan to the mosque, where we saw the people in scattered groups, one man praying by himself, and another man praying with a group of people following his prayer. ‘Umar said: “I think that if I unite these people behind one reciter, it will be better.” Then he decided to do that, so he united them behind Ubayy ibn Ka‘b.’ [Sahih al-Bukhari 2010]

Imam Attabary, mentioned in his history book, that this happened in the Year 14H around 636 A.D. Then Omar  sent a letter to other towns asking them to pray night prayers under one Imam in the mosques.

sent a letter to other towns asking them to pray night prayers under one Imam in the mosques.

There might be a misconception among some that Taraweeh prayer was established by Omar ibn Al-Khattab  . However, it is crucial to clarify that Taraweeh was initiated by the Prophet

. However, it is crucial to clarify that Taraweeh was initiated by the Prophet  .

.

After the passing of the Prophet  , the initial concern of Taraweeh becoming obligatory no longer existed.

, the initial concern of Taraweeh becoming obligatory no longer existed.

Omar ibn Al-Khattab  , recognizing this change, gathered the people under one Imam for Taraweeh prayers. This action did not invent the prayer itself but rather organized the community in congregational worship.

, recognizing this change, gathered the people under one Imam for Taraweeh prayers. This action did not invent the prayer itself but rather organized the community in congregational worship.

The term Taraweeh, derived from the Arabic word “Tarweeh,” meaning ‘rest’, likely came into use during or after the era of Omar  . Unfortunately, I was not able to find solid evidence of when the usage of the term Taraweeh began.

. Unfortunately, I was not able to find solid evidence of when the usage of the term Taraweeh began.

The names for voluntary night prayers as used in the Quran and hadith are called night prayer (Salat al-Layl), Tahajjud, Qiyam, or Qiyam Ramadan. Taraweeh is the plural of the Arabic word Tarweeh, meaning rest. Worshippers used to engage in extended Rakat and take breaks in between, giving rise to the name Taraweeh.

How Many Rakat Did Muslims Pray at the Time of Omar ?

?

It was narrated by Imam Malik in his Book al-Moata, that Sayeb ibn Yazeed said that Omar Ibn Al-Khattab  ordered Obai Ibn Kaab and Tamim Ad-Dary to lead people with 11 Rakat. He said the Qari (Imam) used to read 100’s of Ayat and we used to lean on sticks because the standing would be too long and we used to leave at Fajr time

ordered Obai Ibn Kaab and Tamim Ad-Dary to lead people with 11 Rakat. He said the Qari (Imam) used to read 100’s of Ayat and we used to lean on sticks because the standing would be too long and we used to leave at Fajr time

جاء في موطأ مالك: عن محمد بن يوسف عن السائب بن يزيد أنه قال:” أمر عمر بن الخطاب أبي بن كعب وتميماً الداري أن يقوما للناس بإحدى عشرة ركعة ” قال:” وقد كان القارئ يقرأ بالمئين حتى كنا نعتمد على العصيّ من طول القيام وما كنا ننصرف إلا في بزوغ الفجر “.

Yet in another narration by Abdlrazaq it was said that that Omar Ibn Al-Khattab  unified the prayer under Obai Ibn Kaab and Tamim Ad-Dary on 21 Rakat and used to read 100’s of Ayat and used to leave at Fajr time

unified the prayer under Obai Ibn Kaab and Tamim Ad-Dary on 21 Rakat and used to read 100’s of Ayat and used to leave at Fajr time

أخرج عبد الرزاق في مصنفه عن داود بن قيس وغيره، عن محمد بن يوسف عن السائب بن يزيد أن عمر جمع الناس في رمضان على أبي بن كعب، وعلى تميم الداري على إحدى وعشرين ركعة يقرأون بالمئين وينصرفون عند بزوغ الفجر

ولمالك في الموطأ عن يزيد بن رومان قال: “كان الناس في زمن عمر يقومون في رمضان بثلاث وعشرين ركعة”

In his book Taraweeh Prayer, Mohamed Diyurahman al-Aazami, said: “The more authentic narration is that Omar ordered Obai Ibn Kaat to lease people with prayer eight Rakat, this is confirmed with the action of the Prophet, peace be upon him.”

It appears from various narrations that initially, Ubayy ibn Ka’b began leading the congregation with eight Rakat. However, over time, they increased the number to twenty Rakat.

While the Prophet  himself prayed eight Rakat, there is no record of him prohibiting people from praying more. This flexibility in the number of Rakat is evident in the practices of the Sahaba and the first three generations of Muslims, as indicated by the below hadith.

himself prayed eight Rakat, there is no record of him prohibiting people from praying more. This flexibility in the number of Rakat is evident in the practices of the Sahaba and the first three generations of Muslims, as indicated by the below hadith.

Ibn Umar narrated that once a person asked the Messenger of Allah about the night prayer. He replied, “The night prayer is offered as two Rakat followed by two Rakat and so on and if anyone is afraid of the approaching dawn (Fajr prayer) he should pray one Raka and this will be a Witr for all the Rakat which he has prayed before. [Sahih al-Bukhari 990]

As of this hadith, the night prayer should be offered on two Rakat followed by two Rakat without specification for a limited number.

From Eight to TwentyThe Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad  initially involved praying eight Rakat during the Night Prayer, and these were notably long prayers. However, as the length of the eight Rakat became challenging for some people, a shift occurred towards praying more Rakat with shorter recitations.

initially involved praying eight Rakat during the Night Prayer, and these were notably long prayers. However, as the length of the eight Rakat became challenging for some people, a shift occurred towards praying more Rakat with shorter recitations.

Contrary to a common modern misconception that eight Rakat is shorter and easier than twenty, historical evidence suggests that the initial understanding was different. Dawood Ibn Al-Husain heard the Aaraj saying: The Imam used to pray Surah al-Baqarah in eight Rakat. If the Imam spread the recitation over twelve Rakat, people perceived it as a lightening of the prayers.

عن داود بن الحصين أنه سمع الأعرج يقول: وكان القارئ يقرأ سورة البقرة في ثمان ركعات، فإذا قام بها في اثنتي عشرة ركعة رأى الناس أنه قد خفف

The essence of following the Sunnah is not merely in adhering to a specific number, but, more importantly, in replicating the profound length and devotion exemplified by the Prophet  . It’s crucial to understand that the Sunnah is about offering eight Rakat with substantial length rather than merely completing eight short Rakat.

. It’s crucial to understand that the Sunnah is about offering eight Rakat with substantial length rather than merely completing eight short Rakat.

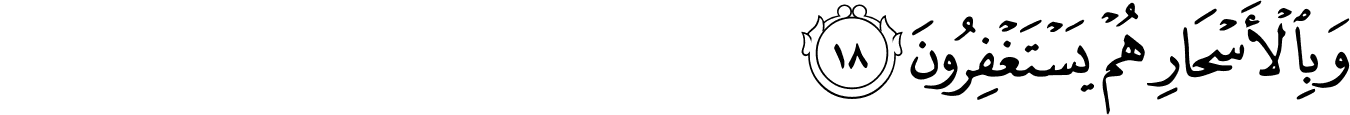

Taraweeh in Makkah and MadinaDuring the time of Umar ibn al-Khattab

, the number of Rakat increased from eight to twenty, not as an attempt to supersede the Sunnah but to accommodate the people’s needs. This adjustment aimed to make the prayers more manageable by introducing shorter Rakat and intervals between them. The name “Taraweeh” itself is derived from the rest or break between these prayers, emphasizing the thoughtful consideration given to the worshipers’ comfort and convenience.

Makkah (PC: Izuddin Helmi (unsplash)

In the early days, the people of Madina and Makkah both observed Taraweeh prayers with twenty Rakat, taking a break after every four Rakat. However, a unique tradition emerged in Makkah, where during the breaks, worshippers would perform Tawaf around the Ka’abah. Seeking to match this special practice, the people of Madina increased the number of Rakat to thirty-six, replacing the four times of Tawaf with an additional four Rakat for each Tawaf. Imam Nawawi and other scholars have documented this historical development.

Imam Shafi said “I have seen the people of Madina praying thirty-nine Rakat and people of Makkah twenty-three Rakat. All these are fine.” He also said, “If they made the standing longer and Rakat less, this is fine. If they made the Rakat more and the recitation lighter that is also good but the first option is more beloved to me.”

By this time, the common practice across major Islamic cities was to pray twenty Rakat, with the exception of Madinah, where they observed thirty-six Rakat during Taraweeh, and other exceptions where people prayed more or less than twenty Rakat.

Beautiful VoicesMuslims have historically shown a preference for praying behind Imams endowed with beautiful voices and deep concentration in their prayers.

The imams of Taraweeh prayers were not only Hafiz (those who memorized the Quran) but often distinguished scholars and judges. Renowned figures such as Imam Attabary, a great scholar of Tafsir, Imam al-Qurtubi, Sheikh al-Islam Ibn Taymiyyah, and other eminent scholars were known for leading Taraweeh prayers.

In his book “The History of Baghdad,” Alkhateeb al-Baghdadi narrates an incident where Ibn Mujahid, upon hearing Imam Attabari lead Taraweeh in his mosque in Baghdad, remarked to his student, “I didn’t even know that Allah  would create someone who reads so perfectly.”

would create someone who reads so perfectly.”

Historian Ibn al-Wardi said: “I prayed Taraweeh behind Ibn Taymmiyya and have seen in his recitation such khushu (devotion) and heartfelt emotion that encompasses the hearts.”

Numerous historians and Muslim travelers who journeyed across the world documented the voices of Taraweeh Imams. For instance, al-Hafiz Ibn Hajar, in his book “The Hidden Pearls of the Noble People of the 8th Century,” mentioned Shamsu Deen Azzary Ibn al-Basal al-Muqri, and said about him “He was with a very nice voice and many People would come to him to pray behind him during Taraweeh prayers, and they would crowd in his mosque.

Recent EraIn recent times, a noticeable shift has occurred in Taraweeh prayers, with many Muslims worldwide still observing twenty Rakat. However, there was a notable trend where the length of individual Rakat has become incredibly short, often consisting of just one verse of the Quran. Makkah maintained the tradition of twenty Rakat, but with multiple groups praying simultaneously. Some historians even mention four separate congregations in Makkah, each facing the Ka’bah from a different direction.

In Madina, the practice continued with thirty-six Rakat, occasionally led by multiple Imams and groups simultaneously. This persisted until the Saudi government assumed control of Makkah and Madina, unifying the prayers under one Imam. The Taraweeh prayers were also standardized to twenty Rakat in both holy Mosques.

Across the Muslim world, many mosques adhere to the tradition of twenty Rakat, while others continue with eight Rakat. The variations reflect the diversity of practices among different communities.

Ibn Taymiyyah said “The best approach varies according to the conditions of the worshippers. If they have the endurance for prolonged standing, then performing ten Rakat with three additional ones, just as the Prophet, may God bless him and grant him peace, used to pray for himself in Ramadan and at other times, is considered optimal. However, if they find it challenging, then praying twenty Rakat is better, and this aligns with the practice followed by the majority of Muslims.”

The history of Taraweeh prayer reflects the devotion of Muslim communities and their commitment to do extra night prayers. As we engage in Taraweeh during the blessed month of Ramadan, let us cherish the rich history and traditions that have shaped this special act of worship. May our prayers be a source of reflection, forgiveness, and spiritual growth, embodying the spirit of unity and devotion that has characterized Taraweeh throughout the centuries.

Related:

– The Sacred Elixir: The Night Prayer And The Ordinary Muslim

– 21 Ways to the Sweet Taraweeh

The post The Origin And Evolution Of The Taraweeh Prayer appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

The Long Road To Muslim Bangsamoro: 10 Years On

It has been a half-century since one of the most remarkable struggles for autonomy by a Muslim minority began, in what is now the Philippines’ southwestern region of Mindanao. Long inhabited by a collection of Muslim ethnic groups known collectively as Moros, this region had a history of Muslim autonomy and fierce resistance to outsiders. Its controversial affixation to the Philippines, and a general history of neglect that mounted by the 1970s to violent persecution, provoked a long-running war punctuated by bouts of diplomacy, frequent splinters, fallouts, and renewed conflict. The Manila Accord, signed ten years ago this month, at last afforded an effective if imperfect autonomy to the Muslim region now known as Bangsamoro, or Land of the Moros.

BackgroundSituated on the eastern perimeter of the Muslim world as it is, the Moro struggle has rarely received the attention it deserves. Like much of eastern Asia, various ethnic groups in the region converted to Islam gradually through the influence of wandering preachers and merchants, so that by the fifteenth century several maritime Muslim sultanates had emerged. Over the course of the next few centuries, they had trade relations with their neighbors interspersed with conflict, but from the nineteenth century successive colonial empires entered the region, each met with local resistance. First was the Spanish Empire, who coined the term “Moro” – ironically from the Spanish “Moor”, used for North Africans at the opposite western end of the Muslim world; last was the Japanese Empire during the Second World War. And in between was the nascent American Empire, fresh off defeating Spain in the Philippines. Early conviviality, brokered by the Ottoman sultanate, soon escalated into hostility, local resistance, and a ruthless decade-long war, where the famed American generalissimo John Pershing cut his teeth. In their first war on land against a Muslim opponent, so unnerved were the American army by their opponents’ ferocity on the battlefield that they sought to combat the Muslim belief in martyrdom by, infamously, burying their opponents with dead pigs.

Subsequent Moro opposition to the Japanese Empire thereafter saw their terrain lumped in with the Philippines, a country that took pride in being East Asia’s only Christian country. Reflecting colonial education, early Philippine elites saw the province’s poverty as a sign of Muslim backwardness and generally dealt only with a select Muslim aristocracy that, in turn, sought to protect its own privileges. Manila also promoted land settlement by Christians from the Philippine mainland who came to exchange predatory deals with the Moro elites at the cost of Moro society at large.

A Fight for SurvivalThe generally accepted trigger for the Moro revolt came in the spring of 1968, when a Philippine army battalion – led, ironically, by a Muslim convert, Abdul-Latif Martelino – slaughtered Muslim recruits who refused to fight in a territorial dispute over the neighboring Sabah region of Malaysia. This was followed by gang warfare, partly linked to competing political elites, where the Philippine army systemically backed murderous thugs of Christian background to go on killing sprees: one infamous case in the summer of 1971 saw families butchered in a mosque.

This outraged Moro society such that even elites such as Udtug Matalam and Rashid Lucman called for political change if not revolt. Malaysia was similarly annoyed: it was no coincidence that Sabah premier Mustafa Harun, whose land was threatened by the Philippines, began to train Moro fighters, while former Malaysian prime minister Abdul-Rahman bin Abdul-Hamid used his forum at the Organization of Islamic Cooperation to bring attention to the Moros. Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddhafi, then in an early Islamic phase of his long and evolving career, was a particularly influential early supporter, calling the conflict a genocide and lending financial and diplomatic support. The Organization has since attracted legitimate criticism for its somnolence, but in those early days it was quite active on the Moro file.

But by far the longest-lasting call for change came from local Moros, including student activists, peasants, and Islamic students. Reflecting a mixture of populism, Islamic identity, and popular culture, insurgents took on roving nicknames as varied as “Solitario”, “Mukhtar”, and “Tony Falcon”. Insurgent leaders included Nur Misuari, a charismatic activist from Sulu, and Salamat Hashim, an Islamic revivalist from Maguindanao who sought to match political and Islamic resurgence. In autumn 1972 – as Ferdinand Marcos imposed emergency rule over the Philippines to become a dictator – Misuari launched the Moro National Liberation Front, which called for independence and engaged in fierce warfare with Marcos’ army over the mid-1970s. Infamously, in February 1974 the army destroyed the historic town Jolo, while such provinces as Cotabato and Maguindanao became constant battlefields. But insurgent resilience and pressure by Muslim states forced Marcos to the 1976 Tripoli Accord, mediated by Libyan foreign minister, which vaguely promised autonomy and Islamic law.

The Costs of DivisionYet Marcos stalled, instead trying to break up the opposition and coopt local elites. In many cases commanders would surrender in return for protecting their communities from the army by acting as local militias; in other cases it was pure opportunism. From the late 1970s a number of senior commanders broke away: Abulkhair Alonto and Jamil “Junglefox” Lucman, both from aristocratic families, defected from the insurgency, while Dimasangcay Pundato and Salamat, unhappy with Misuari’s leadership, broke away. Salamat’s Moro Islamic Liberation Front was by far the more influential: with a stronger emphasis on Islamic social renewal and embedding local ties than Misuari’s loosely organized group, it soon attracted a mass following that continues to this day.

Left to right: Murad Ibrahim, emir of Bangsamoro and the Islamic Front; Nur Misuari, leader of the National Front and former regional premier; and Muslimin Sema, another independence leader. [Photo by Carolyn Arguillas for Mindanews]

While the war did not return to the ferocity of the mid-1970s, the 1980s and 1990s saw on-and-off conflict interspersed with negotiations. The overthrow of Marcos in 1986 promised a brighter future, yet Hashim’s Islamists – by now the biggest rebel group – were excluded from talks. Eventually, an autonomous Muslim region was formed in 1990, with Zacaria Candao, a politician acceptable to both the Islamists and the government, as its premier. Eventually Misuari, after signing an Indonesian-mediated deal in 1996, returned from the wilderness as Muslim premier, subsequently proving a poorer governor than rebel.Only part of the Muslim-majority region was included in the autonomy deal, while the Islamic Front lacked formal recognition in spite of their strength on the ground. The Islamists’ system of camps and bases were really sprawling communities, with public services, education, and a fairly disciplined military and security apparatus: Salamat and his main lieutenants, Murad Ibrahim and Abdul-Aziz Mimbantas, were as much respected community leaders as commanders. Continued exclusion prompted some militants to form more brutal groups: one example was the Janjalani brothers Abdul-Raziq and Khadaffy, whose network mounted a series of massacres and atrocities that ran quite separate to, but occasionally attracted defectors from, the main Islamic Front.

War and PeaceDuring the late 1990s, the Islamic Front engaged in a mixture of battles and negotiations with governments: battles would often be accompanied by tortuous negotiations between government officials and the Islamic Front’s foreign minister Ghazali Jafar. The talks were at an advanced stage when, at the turn of the millennium, the impatient ruler Joseph Estrada, a former actor who lacked statesmanship, announced an “all-out war”. By July 2000 the army had captured the Islamists’ headquarters at Barira, yet this only provoked a long-running insurgency, during which Salamat passed away and was replaced with Murad.

The Philippine government tried with limited success to frame its campaign as part of the “war on terror” – helped, inadvertently, by the continued violence of the Janjalani network – yet by the late 2000s it was obvious that talks should resume. A renewed agreement on autonomy in 2008 was promptly thrown out, under pressure from Christian politicians, by the Philippine Supreme Court. The war was complicated, meanwhile, by violence and criminality from communities and families linked to both the government and its opposition. Though the Islamic Front enhanced its internal discipline during Murad’s leadership, disconsolate commanders – most famously veteran field commander Umbra Cato – rejected the talks and broke away. Misuari, sacked as premier in 2001, subsequently organized two attacks, first at his hometown Jolo, and then, a decade later in 2013, on the bigger city of Zamboanga. Even the heir of the Sulu sultanate, the first Moro sultanate based at Jolo, surfaced at Malaysia’s adjacent Sabah region to lay claim to their title.

It was against this backdrop that Malaysian diplomat Abdul-Ghafar Mohammad resumed mediation with increased urgency. The Islamic Front was represented by Mohagher Iqbal, a veteran writer and diplomat for the Islamists, while the government was represented by the academic Miriam Coronel-Ferrer, who withstood considerable criticism to accommodate an insurgency whose grievances she felt were legitimate. The Manila Accord they signed in the spring of 2014 put the Muslim-majority region under Bangsamoro, with the Islamic Front as governing authority while the army would remain for an interim period.

That period expired in 2019, and Bangsamoro has been ruled by Murad Ibrahim since. There have been loose ends, particularly during the transitional period of 2014-19: in 2017, most infamously, the Janjalanis’ roving successor Isnilon Hapilon joined Daesh and laid a six-month siege to the city of Marawi. The Islamic Front, whose security warnings had been neglected by Manila, was embarrassed enough to actively target dissidents themselves, provoking criticism by Cato’s successors for working alongside the non-Muslim government forces. Like the splinter groups of the 1980s, these small militias have been a headache, operating deep in the undergrowth and often supported by their communities for localized reasons. Such problems are predictable, both owing to the long conflict and the decentralized nature and local disputes in the region.

Yet in spite of these hurdles, the transitional phase passed and today Bangsamoro is an autonomous, if imperfect, region: officially linked with the Philippines, it runs its own institutions, law, military and security, and public services. Amid the torrent of dispiriting news often associated with the repression of Muslim politics and militancy, the Bangsamoro tale offers uplifting lessons. It is notable that foreign Muslim states played an unusually helpful role that is not often afforded to other Muslim militants; it is notable, too, that the Philippine government reformed its worst instincts and eventually opted for a more sensible course. But none of this could have happened without the perseverance, societal renewal, and resolve of the Moro peoples.

Related:

– Quran Speaks Interviews Dr Wajid Akhter: Why Islamic History Matters

– A Dollar or a Dua for the Philippines

The post The Long Road To Muslim Bangsamoro: 10 Years On appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

What a teacher in hiding can tell us about our failure to tackle intolerance | Kenan Malik

A class about free speech was cynically exploited by activists to incite fury in a local community

Three years ago, on 25 March 2021, a teacher from Batley Grammar School (BGS) in West Yorkshire was forced into hiding after a religious studies class he gave led to protests from Muslim parents and to death threats. Today, that incident has been largely forgotten. Except by the teacher. He can’t forget it because, extraordinarily, he and his family are still in hiding. Equally extraordinarily, little is said about this.

The debate about the events at BGS, like many about Islam, blasphemy and offence, has been framed by two polarised arguments. Many on the reactionary right (and not just the reactionary right) view such confrontations as the unacceptable price of mass immigration and the inevitable product of a Muslim presence in western societies. Many liberals and radicals, on the other hand, think it morally wrong to cause offence, believing that for diverse societies to function, there is a need to self-censor so as not to disrespect different cultures and beliefs. Neither argument bears much scrutiny. The most comprehensive account of the events at BGS comes in a review published last week by Sara Khan, the government’s independent adviser on “social cohesion and resilience”. The lesson that sparked the controversy was designed, ironically, to explore issues of blasphemy and free speech, and of appropriate ways of responding to religious disagreements.

Continue reading...Standing At The Divine Window: A Glimpse Of Eternity In The Serenity Of Salah

We live in a world where windows are more than mere glass: they are silent witnesses to our deepest dreams. Time and time again, our films and literature, across eras and genres, capture characters gazing longingly toward the sky or horizon. Their gazes transcend the mere act of outwardly observing the tapestry of this world. They’re caught lost in the pursuit of something greater.

“The world is a prison for a believer,”1 our beloved Prophet and Messenger ﷺ tells us. And who understands the blessing of the small window in the encaging walls better than the prisoner, who overlooks the world outside from within? For a prisoner, the austere cell whispers tales of tangible isolation and confinement. Somber realities nestle within the barren walls that have never known the comfort of warmth. Inside, time takes on a rhythm entirely its own as the prisoner paces across the bare floor to break the stillness of the prison room. Life here is reduced to its most fundamental essence.

And yet, the small window frame is a sliver of the world beyond—a sliver of hope to temporarily appease a soul yearning for a freedom that lies just beyond the prisoner’s grasp. Through it, the prisoner can taste light, witness the passing of night and day, spring to winter, and hear a distant symphony of voices. Through it, the prisoner sees the passing of time, which means holding on just a little longer. Resilience is born in the grimmest of spaces as long as there’s a sliver of light.

To the Muslim, the vastness of the earth mirrors the cold, confining walls of a prison cell. The pleasures of this world are but faint, fleeting echoes of Paradise. Countless times we reach for the pleasures of this world, only to realize they’re mere mirages eluding our grasp.

The Return HomeAs humans, we’re forever searching to return home. Yet many spend lifetimes without ever understanding where “home” truly lies. Instead, as sloppily as a child building a gingerbread house, we construct fragile illusions of “home,” only to end up unsatisfied before leaving them behind. Home lies in a realm that transcends the limitations of human experience. In the words of the King of kings ﷻ,

“this worldly life is not but diversion and amusement. And indeed, the home of the Hereafter – that is the [eternal] life, if only they knew.” [Surah Al-Ankabut: 29;64]

Sweetness of salah [PC: Sinan Toy (unsplash)]

Humans are prisoners awaiting their return home, with a window that opens up for us five times a day out of the mercy of Allah ﷻ, for those who know and believe. The homes of this world, made of brick and mortar, pale in comparison to the homes of the Hereafter. Our Beloved Messenger ﷺ said, Paradise is built from “bricks of silver and gold, its mortar is musk of strong fragrance, its pebbles are pearls and rubies, and its soil is saffron. Whoever enters it will enjoy bliss without despair and eternity without death. Their clothes will not fade, nor will their youth expire.”2 For the believers, their homes reside in the “Gardens of Eternity; beneath them rivers will flow; they will be adorned therein with bracelets of gold, and they will wear green garments of fine silk and heavy brocade: They will recline therein on raised thrones. How good the recompense! How beautiful a couch to recline on!”3 For “those who fear their Lord will have high rooms upon rooms built under which rivers flow. [This is] the promise of Allah. Allah does not fail in [His] promise.”4In His infinite mercy, Allah ﷻ has given the believer a window—a spiritual escape from the confines of this worldly prison. Five times a day, He ﷻ invites us to stand in prayer before Him ﷻ, allowing us to linger at this window of transcendence for as long as we want, to gaze upon the divine and converse with our Lord ﷻ. In His infinite wisdom and compassion, five times a day, He ﷻ offers us a temporary escape, to catch a whiff of the sweet fragrances of the Gardens of our homes in Jannah (Paradise). The pillar of prayer in the Islamic tradition is a gift to us from Allah  brought by our beloved Messenger

brought by our beloved Messenger  after his journey to heaven on the Night of Ascension, the Night of Al-Isra Wal-Mi’raj. He ﷺ said, “When you get up to pray, perform ablution perfectly, then face the qiblah and say: ‘Allāhu Akbar’ (Allāh is Greater). Then recite a convenient portion of the Qur’ān; then bow and remain calmly in that position for a moment, then rise up and stand erect; then prostrate and remain calmly in that position for a moment; then rise up and sit calmly; then prostrate and remain calmly in that position for a moment; then do that throughout your prayer.” [Reported by as-Sab’a and the wording is that of al-Bukhari]

after his journey to heaven on the Night of Ascension, the Night of Al-Isra Wal-Mi’raj. He ﷺ said, “When you get up to pray, perform ablution perfectly, then face the qiblah and say: ‘Allāhu Akbar’ (Allāh is Greater). Then recite a convenient portion of the Qur’ān; then bow and remain calmly in that position for a moment, then rise up and stand erect; then prostrate and remain calmly in that position for a moment; then rise up and sit calmly; then prostrate and remain calmly in that position for a moment; then do that throughout your prayer.” [Reported by as-Sab’a and the wording is that of al-Bukhari]

We offer our prayers to our Lord ﷻ, but it is we who reap the rewards and benefit. God does not need to see us stand at the window. He ﷻ knows our need for it, and so He commanded it. Every command from Allah ﷻ bears fruit for the believer. Ibn al-Qayyim al-Jawziyyah, a prolific Islamic scholar wrote,

“The fruit of fasting is the purification of the soul. The fruit of zakah (obligatory alms) is the purification of wealth. The fruit of Hajj (pilgrimage) is forgiveness. The fruit of jihad (fighting is submitting the soul) is that Allah has purchased from his servants their lives and their properties in exchange for Paradise. The fruit of salah (prayer) is the turning of the servant upon his Lord and the facing of Allah given to His servant. However, embarking towards Allah with complete devotion in salah encompasses all the aforementioned fruits because the fruits of all good deeds are found when the ‘abd embarks toward Allah with true devotion.”5

He ﷻ loves to see His faithful servant stand to worship Him. And who better to worship than “Allah, [who is] One, Allah, the Eternal Refuge. He neither begets nor is born, Nor is there to Him any equivalent.” [Surah Ikhlaas: 1-4] His faithful servant, marked by “the sign [of brightness seen] on their faces from the trace of prostrating [in prayer],” loves to stand to meet their Lord in profound moments of devout love. Indeed, “does not every lover love to be alone with his beloved?”6

A Meeting With Our BelovedIn the quiet hours of the night, while the world slept, our beloved Messenger ﷺ, whose heart held love for his wife and deep devotion to his Lord, turned to our mother Aisha  with a question of reverence: he ﷺ said, “O Aisha, would it grieve you if I spend this night in worship to my Lord?” Her reply to the Messenger ﷺ only echoed their love; she said, “By Allah, I love to be close to you and I love what pleases you.”7 And thus, the Prophet

with a question of reverence: he ﷺ said, “O Aisha, would it grieve you if I spend this night in worship to my Lord?” Her reply to the Messenger ﷺ only echoed their love; she said, “By Allah, I love to be close to you and I love what pleases you.”7 And thus, the Prophet  left the warmth of his bed and the side of his wife, to stand in serene submission before the One who captivated his heart even more than his beloved wife, his Beloved Lord. The entirety of the universe is obedient to Allah ﷻ,

left the warmth of his bed and the side of his wife, to stand in serene submission before the One who captivated his heart even more than his beloved wife, his Beloved Lord. The entirety of the universe is obedient to Allah ﷻ,

“and to Him belongs whosoever is in the heavens and earth. All are to Him devoutly obedient.” [Surah Ar-Rum: 30;26]

Thus, as the universe surrenders to the Lord of the worlds, the believer conforms to the harmony of creation by prostrating to Allah ﷻ. With a head bowed in humility, the believer stands on the prayer mat ready to enter the chamber of prayer with angels, each the size of mountains, standing behind him or her, and to the right and to the left.8

In the presence of these celestial beings and before the revered King of all kings, it is a prophetic practice from the Sunnah of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ to adorn ourselves in beautiful attire and with pleasant scents. Devotion to Allah ﷻ transcends mere physical ritual or cleanliness. It involves purifying our limbs by performing wudu (ablution) and aligning our hearts solely towards Allah ﷻ. This spiritual orientation is a purification as much as it is a conscious turning of our being away from that which is not our Lord ﷻ. A soul anchored in such intentionality, navigating the world in the name of Allah ﷻ, ascends beyond the prison of dunya, this transient, lower world.9 It does not suffer from the pangs of estrangement or the existential catastrophe of aimlessly existing in this ephemeral world. Instead, it finds peace and familiarity in consistently meeting with the Divine, garnering His pleasure, and beautiful, celestial rewards are blossoming in the Gardens of Jannah.

The Sanctuary of Salah

Praying in seclusion [PC: Haei Elmas (unsplash)]

When we raise both our hands up in Takbir to commence the prayer with the phrase Allāhu Akbar (God is Greater), we cast away every burden of this fleeting life, affirming with our hearts that Allah ﷻ is greater than these temporary trials. The veil of worldly illusions is lifted and with the eye of our hearts, we are reminded that Allah ﷻ is the “originator of the heavens and the earth. When He decrees a matter, He only says to it, ‘Be,’ and it is.”10 His authority and power transcend the confines of the austere prison of this world, we only need to ask. In His own words, He ﷻ promised, “Call upon Me; I will respond to you”11 and He ﷻ is the Keeper of His promises. In this private audience with the Divine, the heart speaks to its Creator knowing that He ﷻ understands and responds to our call.However, our worship is not transactional. It is not to have our calls answered. It is to answer the call of Allah ﷻ that we stand to worship Him. We recognize Allah’s  Majesty and fulfill the purpose for which we were created. Allah ﷻ says,

Majesty and fulfill the purpose for which we were created. Allah ﷻ says,

“I did not create the jinn and mankind except to worship Me.” [Surah Adh-Dhariyat: 51;56]

As part of the prayer, the believer, who knows and loves Allah ﷻ, glorifies His Majesty “profusely for His Attributes and Perfection.”12

The essence of recitation of the Quran in the prayer is an “endeavor to learn about Allah  through His words as if trying to see Him through His Revelation.”13 The Quran is a divine love letter, sent to us from our Beloved ﷻ, to know Him, love Him, and to guide our hearts to Him. One of our righteous Salaf (predecessors) said, “Allah manifests Himself to His slave through His speech [the Quran].”14 Thus, we are guided by the divine mercy and light of Allah ﷻ, for “everything which gives light and illuminates other things has received its light from Him; it has no light of its own.”15 He ﷻ “is the light of the Heavens and the Earth.”16 And the creation is a mere reflection of the Creator. The believer is a conduit of His light: reflecting the light of Allah ﷻ and dispelling the shadows of ignorance and corruption in this world. With every prayer, we present our hearts before our Lord ﷻ, seeking to polish and align them with His guiding light.

through His words as if trying to see Him through His Revelation.”13 The Quran is a divine love letter, sent to us from our Beloved ﷻ, to know Him, love Him, and to guide our hearts to Him. One of our righteous Salaf (predecessors) said, “Allah manifests Himself to His slave through His speech [the Quran].”14 Thus, we are guided by the divine mercy and light of Allah ﷻ, for “everything which gives light and illuminates other things has received its light from Him; it has no light of its own.”15 He ﷻ “is the light of the Heavens and the Earth.”16 And the creation is a mere reflection of the Creator. The believer is a conduit of His light: reflecting the light of Allah ﷻ and dispelling the shadows of ignorance and corruption in this world. With every prayer, we present our hearts before our Lord ﷻ, seeking to polish and align them with His guiding light.

When we place our hands over our chests and speak to Him from the depth of our hearts, or bow our heads in humility and our intellect yields to His reverence, Allah ﷻ sees the sincerity of our hearts. The Messenger of Allah ﷺ taught us that

“Allah does not look to your faces and your wealth but He looks to your heart and to your deeds.”[Sahih Muslim 2564c]

As we press our faces to the earth, from it we came and to it we will return,17 our hearts ascend above our intellect and the masks we wear for the world fall away. In the state of sujood (prostration), our burdens lighten, forgiveness is found, and our whispered dua’s (supplications) for mercy are heard and answered by Allah ﷻ. Every word and movement of the prayer draws us closer to Him ﷻ, elevating our spiritual standing, bringing us closer to the Abode of Eternity. This stillness in salah is a sanctuary, fulfilling our deepest psychological, spiritual and emotional needs—needs that no creation can address. We stand with conviction, knowing Allah ﷻ, the Keeper of promises, will accept our sincere devotion out of His boundless mercy:

“And worship your Lord until the certainty [of death] comes to you.” [Surah Al-Hijr: 15;99]

Gazing Towards EternityFive times a day, the people of salah “rise to prayer, rise to success” upon the echoing divine calls of Allah ﷻ. We gaze wistfully from inside the enclosure of this worldly prison through a small window to catch a mere glimpse of the eternity of the Hereafter. Each prayer brings us closer to seeing the majestic face of Allah ﷻ and returning to the true home of Jannah. In a land of thornless lote trees18 and sprouting fruits of seventy-two different colors, and endless “rivers of fresh water, rivers of milk never changing in taste, rivers of wine delicious to drink, and rivers of pure honey”19, the dwellers of Jannah will reside in mansions with “exterior[s] [that] can be seen from inside and interior[s] [that] can be seen from outside.”20 They will visit one another “on white, high-bred mounts that resemble sapphires.”21

In the deepest crevices of our hearts, we long to be among the People of the Right, who see the celestial gates of Jannah open for us, as its keepers say, “Peace be upon you! You have done well, so come in to stay forever,”22 as we’re called to return home. The people of salah will be summoned to enter through their own gate: Baab As-Salah, the Gate of Salah. They will leave behind the ephemeral for the eternal. The pillar of prayer in the Islamic faith is a scent of Paradise that reached the temporal prison of dunya, as it can be smelt from the distance of “seventy autumns.”23 Through the serenity of salah, humanity knows Allah ﷻ, which is a gift unmatched. For “the one who knows Allah, what does he not know? And the one who does not know Allah, what do they know, really? If you know everything else, but do not know Allah, you know nothing.”24

May Allah ﷻ make us of the ones who know Him, love Him, and always strive to please Him with every moment of our existence. May Allah ﷻ make us from amongst the dwellers of Jannat al-Firdous and use us to guide others to His path. Allahumma Ameen.

Related:

– Conversing with Allah: Reflecting On Surah al-Fatihah For Khushoo In Salah

– The Sacred Elixir: The Night Prayer And The Ordinary Muslim

1 Sahih Muslim 29562 Sunan al-Tirmidhī 25263 Quran 18:314 Quran 39:205 Al-Jawziyyah 716 Penfound7 Ṣaḥīḥ Ibn Ḥibbān 6208 Muwatta Malik9 Penfound10 Quran 2:11711 Quran 2:18612 Al-Jawziyyah 6713 Al-Jawziyyah 6814 Al-Jawziyyah 6815 Ala-Maududi16 Quran 24:3517 Quran 20:5518 [Al-Maliki 48]19 [Al-Maliki 58]20 Al-Maliki 3621 Al-Maliki 9822 Quran 39:7323 Al-Maliki 4424 Musab PenfoundThe post Standing At The Divine Window: A Glimpse Of Eternity In The Serenity Of Salah appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Breaking fasts and making tackles: how rugby league is adapting to Ramadan

Hakim Miloudi and London Broncos teammate Iliess Macani hope Super League stars observing Ramadan will inspire others

London Broncos’ Challenge Cup defeat at Warrington Wolves last weekend was largely uneventful given the final scoreline, but there was a moment of huge significance almost everyone would have missed midway through the Broncos’ 42-0 defeat.

Support staff providing players with water is nothing new, but the sight of London’s physio entering the field with a handful of dates specifically for the Broncos’ Hakim Miloudi to break his fast while the game continued perhaps emphasised the work rugby league still has to do to recognise Muslim athletes. “There was no time to stop and break my fast properly, I was making tackles within seconds of eating,” Miloudi smiles.

Continue reading...IOK Ramadan: Do You Value Your Promise to Allah? | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep14]

This Ramadan, MuslimMatters is pleased to host the Institute Of Knowledge‘s daily Ramadan series: Keys to the Divine Compass. Through this series, each day we will spend time connecting with the Qur’an on a deeper, more spiritual, uplifting level.

Previous in the series: Juz 1 Juz 2 Juz 3 Juz 4 Juz 5 Juz 6 Juz 7 Juz 8 Juz 9 Juz 10 Juz 11 Juz 12 Juz 13

Juzʾ 14: Do You Value Your Promise to Allah?

Bismillah-ir Raḥmān-ir Raḥīm. All praise to Allah and peace and salutations upon his servant and final messenger Muḥammad (pbuh), Assalāmu ‘Alaykum wa Raḥmatullāhi wa Barakātuh! Welcome to another episode of our Ramaḍān Reflection series, Keys to the Divine Compass, where we go over verses of the Qur’an from every Juz throughout the month of Ramaḍān so that we can derive lessons and apply them to our lives.

InshaAllah today I will be going over verses 95 and 96 from Sūrah al-Naḥl (Sūrah 16) in which Allah (swt) says, “Do not sell the promise of Allah to gain a paltry sum, whatever is by Allah (swt) is better for you, if only you knew. Whatever is by you is fleeting and whatever is by Allah (swt) is everlasting, and we will absolutely reward those who are patient according to the best of what they had done.” In these two verses, Allah (swt) gives us the mindset of a believer in how we are supposed to treat and value our Dīn. When Allah (swt) guided us, this blessing absolutely topped any blessing that He could give us, after the fact that He gave us the ability to know, acknowledge, and submit to Him.

It is the greatest blessing that we have and if a person finds themselves in a position of compromising their Dīn to achieve something of this world, where the Dīn becomes a non-priority, where we compromise our values to get ahead in this world, to achieve the approval of people who do not have the same priorities and beliefs as us, Allah (swt) gives us a warning. No price that you pay in exchange for getting something in this world, if it means giving up the religion, if it means reneging on the promise that you have made to Allah it is not worth it. Even though Allah (swt) of course says ‘a paltry sum’ it does not mean that hypothetically if it was a higher price, it would be okay. Allah (swt) does not mean that if it was a high enough reward then you can deprioritize your religion and go back on the promise you made to Allah.

Absolutely not! Nothing is worth compromising the Dīn over, and Allah (swt) reminds us that what you are trying to ultimately gain in this world is not valuable in the long run, and even intrinsically it is not valuable when compared to what Allah (swt) has stored for you in the hereafter. But you must know what you are giving up to gain whatever you want in this world. Allah (swt) says in verse 96 that whatever is by you is temporary, that hypothetically you go through with this, you sell the Dīn of Allah (swt), you sell out the community, you sell your principles to gain some approval and value, to gain some objective in this world and do know people like this. Hypothetically you go through with it, what you ultimately gained will end because it is temporary, it is fleeting. You might feel that you have achieved a great thing, you might feel that what you had given up from your principles and from your beliefs was worth what you gained, but that will only last for as long as you are alive in this world because you can lose it earlier as well. Even if you are enjoying that benefit and achievement throughout the rest of your life, when you are gone you cannot take it with you. Contrast to what Allah (swt) has kept in store for you, that is everlasting. It is always there and worth being patient over any gain that you might achieve in this world.

Often, especially for people who are in very high positions, when they think that they might be able to affect some type of change, but to affect change they must give up something, usually the first thing to be compromised is religion. Nobody thinks of taking a pay cut, nobody thinks of getting a demotion, nobody thinks of leaving whatever they are doing, but when it comes to compromise the first thing that is typically compromised are the religious values, the principles that Allah (swt) and the Prophet (pbuh) taught us. Allah (swt) reminds us to be principled in these verses, that whatever you think you can gain by giving up on your values and principles in this world is not going to be worth it, because you are giving up something that is permanent, everlasting in exchange for something that is temporary. Even if it was worth it in the moment, on the day of judgment when the believers are being rewarded for their patience and for the best of their actions you will have wished you did the same.

May Allah (swt) protect all of us from compromising our principles and values to gain the approval of those who do not have the same objectives and priorities as us. May Allah (swt) guide, bless, and protect us all. Assalāmu ‘Alaykum wa Raḥmatullāhi wa Barakātuh.

The post IOK Ramadan: Do You Value Your Promise to Allah? | Keys To The Divine Compass [Ep14] appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Not just genocide but deliberate ecological disaster

A Ramadan Quran Journal: A MuslimMatters Series – [Juz 19] Of Plans, Parenting And Genocide

This Ramadan, MuslimMatters reached out to our regular (and not-so-regular) crew of writers asking them to share their reflections on various ayahs/surahs of the Quran, ideally with a focus on a specific juz – those that may have impacted them in some specific way or have influenced how they approach both life and deen. While some contributors are well-versed in at least part of the Quranic Sciences, not all necessarily are, but reflect on their choices as a way of illustrating that our Holy Book is approachable from various human perspectives.

Introducing, A Ramadan Quran Journal: A MuslimMatters Series

***

Of Plans, Parenting & Genocideby Hiba Masood

I love how we console each other with verses from the Quran. I love how we gear up for the last ten nights of Ramadan. I love that we’re thrilled if someone we know is invited for Umrah. I love that if one of us sneezes the other has a blessed response. I love how every time someone has praised my work they have given me a dua’.

I love Muslims with an earnestness that hurts. The Ummah is my most favorite thing in the world. To see it in pain gives me a deep searing grief. And to work for it, the greatest privilege I had never imagined to be afforded.

Recent months have made clear that the past was a mirage and the future is uncertain. We need strength and optimism to face whatever lies ahead. We need a plan. With a capital P.

Each and every one of us must urgently and immediately consider how we can expand our circle of influence, how we can be distributors of truth and goodness in our respective communities, how far into these turbulent waters we can throw the net of tawheed and righteousness, what changes we must make to life to become leaders and raise warriors in the army of Allah  .

.

You know, those warriors we gave birth to. The ones in the next room right now, probably squabbling over iPad time.

The more I worry over how my kids are turning out and the more I see the ummah suffering, the more focussed my dua’ has become. I find myself suddenly unable to pray anything but the one specific dua’ which keeps coming to mind and tongue, almost unbidden. Again and again, I recite:

˹They are˺ those who pray, “Our Lord! Bless us with ˹pious˺ spouses and offspring who will be the coolness of our eyes, and make us leaders for the righteous.” [Surah Al-Furqan: 25;74]

Every time I see a brave man from Gaza consoling his family with verses from the Quran, I recite:  emphasis on the part about the pious spouse.

emphasis on the part about the pious spouse.

Every time I see a Palestinian mother weeping over her lost children, I recite:

emphasis on the part about my children being the coolness of my eyes.